|

||||||||||||||||||||

Joseph Nash, published by Dickinson Brothers, Hardware at the Great Exhibition, 1852, Victoria and Albert Museum, London |

The Advent of Modern Global

A new Carnegie Museum of Art exhibition recounts a time of thrilling progress and ingenuity through objects assembled from past world’s fairs, where the world exchanged big ideas on modern living.

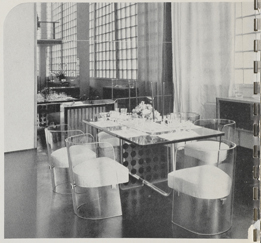

That now-obsolete futurism, including a glass chair made right here in Pittsburgh by the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Co. (PPG), will once again be on grand display this fall at Carnegie Museum of Art. “It was a modern marvel in glass,” says Jason T. Busch, chief curator and The Alan G. and Jane A. Lehman Curator of Decorative Arts and Design at Carnegie Museum of Art. “It was streamlined, hygienic—one piece of glass forms the back, the arms, the legs.” Looking at the prototype today, a treasured work in the Museum of Art’s permanent collection, one can still sense the optimism that pervades it—the belief in a future peeking out from behind the Great Depression. Inventing the Modern World: Decorative Arts at the World’s Fairs, 1851–1939, a major new traveling exhibition created by Carnegie Museum of Art in partnership with The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, showcases historic advancements in the materials and methods used to bring us many of today’s everyday items. More than 200 objects will go on view in Pittsburgh beginning October 13, each a past participant in a world’s fair (or a model or prototype of an object debuted at a fair) predating the 1940s. The fairs of those days obsessed over the avant-garde of production and materials, touting everything from tools to jewelry, furniture to textiles. The extravagant gatherings were the first truly globalized sharing of ideas and ingenuity, explains Busch, the exhibition’s co-curator. The result, he adds, “was the creation of modernity as we understand it today.” The next big thingThe Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, the first world’s fair, was held in 1851 in London’s Hyde Park. It would come to serve as a model for the fairs that followed, combining industrial design and manufacturing with an artistic aesthetic, a spirit of competitive progress and national pride, and the sharing of both traditional and newly discovered styles and techniques from around the world. Among the 100,000 objects that debuted that year: an early bicycle, several steam engines, and the world’s first public toilet. “There are great parallels to be drawn to our digital age,” says Rachel Delphia, the Museum of Art’s associate curator of decorative arts and design. “Today we have instant access to information; we don’t have to go further than our smartphones to seek out this newness. But the fairs themselves were the first attempt to marshal all of this innovation into a format where it could be appreciated en masse.” World’s fairs have been highly influential in what we are as an institution, and for 30 years we have collected with that in mind ...

- Jason T. Busch, co-curator of Inventing the Modern World

Of the works displayed in Inventing the Modern World, the majority are limited-production objects for modern living. Their diversity and creativity highlight not just the important cultural and aesthetic changes of the period, but the exquisite craftsmanship and ingenuity of the artists and manufacturers who made them. The show is ambitious to say the least; Busch, curatorial assistant Dawn Reid, and co-curator Catherine Futter at The Nelson-Atkins labored for years, borrowing objects from 45 lenders in nine countries. Fortunately for Carnegie Museum of Art, three dozen of the show’s works have a permanent home in its collections, and dozens more of the museum’s holdings will be on view exclusively during the Pittsburgh presentation. In fact, Inventing the Modern World has been a guiding force in making acquisitions, especially since Busch arrived at the museum in 2006. “World’s fairs have been highly influential in what we are as an institution, and for 30 years we have collected with that in mind— now more assertively because of this show,” notes Busch.

This practice of using a major exhibition to expand its permanent collection is a trademark of the museum’s marquee exhibition, the Carnegie International, in which contemporary art is borrowed, exhibited, and in many cases purchased to expand the museum’s holdings of the “Old Masters of tomorrow.” Perhaps not coincidentally, that very idea can be traced, in part, to the world’s fairs—as can other key elements of Pittsburgh’s industrial and cultural heritage. Pittsburgh on the world stageIn 1893, Andrew Carnegie and his lifelong friend and business partner Henry Phipps, Jr., traveled to the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. There, Carnegie found inspiration and objects for his Carnegie Institute. The idea for the cast collection in the Museum of Art’s Hall of Architecture, for example, came directly from casts he saw in Chicago. What’s more, Carnegie saw a direct relationship between the sharing of knowledge at the fairs and his own belief in cultural charity, and he would subsequently write about the value of such exchange. Phipps, too, found great inspiration in the 1893 fair; after the event ended, he purchased the fair’s botanical exhibits as the seeds for Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens, which opened in Pittsburgh later that year. Phipps is one of several Pittsburgh mainstays joining Carnegie Museum of Art in celebrating the city’s cultural ties to the world’s fairs; the conservatory’s annual garden railroad display will carry a world’s fair theme. And The Frick and The Warhol plan to highlight their respective namesakes’ fascination with the global affairs.

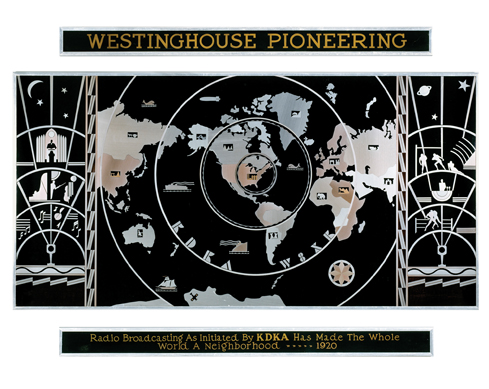

By 1939, Pittsburgh and the world’s fairs had become inextricably tied, thanks to the city’s renown for industry and innovation. Pittsburgh manufacturers such as PPG, US Steel, and Heinz became regular contributors. Technological watersheds such as Westinghouse and KDKA’s radio and television displays, not to mention the iconic Ferris Wheel—first created by Pittsburgh engineer George Ferris in 1893—became must-see features of the recurring events.

“That fair would’ve been the first time most people touched fiberglass,” notes Stewart. “Our interactives will show how manufacturers took a typically lengthy handmade process and industrialized it to make spectacular objects in a more economical way.” Beauty en massePlate glass was an obviously novel material when it took the global stage; most people visiting The House of Glass would not have previously seen glass furniture that could support a person’s weight. But the ingenuity behind an object featured at the 1876 world’s fair in Philadelphia would have been much less obvious to the average viewer, even in the 19th century.

The Elkington vase is an example of cloisonné—a traditional technique using metal to decorate objects, popular in the Near and Far East and very desirable to 19th-century consumers. While traditional cloisonné was excruciatingly time consuming, Elkington created an electroforming process that skipped over the initial metalworking. To illustrate this in the exhibition, Stewart shows a box of tiny vases, each one representing a single step in the traditional technique. “When you electroform it, you immediately cancel out all this insanity,” says Stewart, passing her hand over the first of several vases in the timeline. “You still had to do a lot, but Elkington developed this process to essentially mass-produce a particular vessel.”

“The world’s fairs go hand in hand with industrial design,” adds Delphia. “This is when things go from being unique, handcrafted objects whose success is ultimately determined by the skilled hand of the artisan, to the well-executed design that can be mass-produced.” With its Eastern design and Western mass production, the Elkington vase embodies the best of what the world’s fairs were all about: cross-cultural exchange. In this case, it’s a British manufacturer borrowing from Asian themes: the Japanese-style bird and design elements, even colors, in the Elkington vase are unambiguous. But that cross-cultural exchange went both ways, and just as the West borrowed from the East, Asian artists and designers learned much from the world’s fairs as their nations opened up to the world. East meets westFour panels of lacquered wood stand 10 feet tall; a screen to divide a room in two. Painstakingly embroidered onto the panels is a scene of tumultuous, churning waves. Hashio Kiyoshi’s Morning Sea was first shown to the world in 1915 at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, a world’s fair held in San Francisco. There’s something subtle about Morning Sea that might be an early-20th-century hint at the globalized world we inhabit today. “In terms of technique,” says Busch, “this is not a painted decoration; it’s created by embroidering thousands upon thousands of strands of silk of about 250 shades. Combine that with the fact that it has the crispness and clarity of a photograph—an art form invented in the West—and you’ve got something markedly advanced. In 1915, this only could’ve occurred with the exposure of Japan to advancements of the West.

“It’s the blockbuster of the exhibition,” he says emphatically. Cross-culturalism is a unifying theme of the show, which will travel next to New Orleans Museum of Art and the Mint Museum in Charlotte, North Carolina. But while exchange was open with nations such as Japan and China, fairs were essentially Western institutions with Western values. “This was a time of imperialism, of colonialism,” Busch explains. “It’s something we don’t celebrate in this exhibition, but we don’t bury our heads in the sand either. We have to recognize those influences.” As one example, in the 1897 world’s fair in Brussels, King Leopold II made an attempt at justifying his massive, and brutal, acquisitions in the Belgian Congo with objects inspired by Congolese designs and materials, made by Belgian designers. Similarly, French objects from the 1860s such as Joseph Cremer and Co.’s cabinet use trophies from the colonization of the South Pacific alongside more traditional French motifs. “All of a sudden, through these objects, this show reveals a bit of social, political, and artistic history,” adds Busch. “Nations were born and disappeared, the processes and marvels we take for granted today were debuted. The world as we know it today was really built during the world’s fairs of this era.”

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Ripped from the Headlines · Drilling for Data · Perspective: Making Museums Matter · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Robert Marshall · Science & Nature: Women’s Work · Artistic License: Personal Pop · First Person: A Feathered Face of Forest Fragmentation · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |