Fall 2012

Fall 2012|

“Culture, high and low, is what made the rest of the world want to come here or be like us. So I am celebrating it.”

- Deborah Kass |

Personal Pop

The Warhol highlights the work of Deborah Kass, who’s spent a career exploring power, gender, and ethnicity in pop culture.

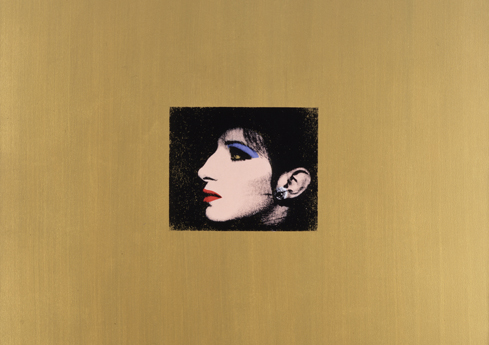

Looking at her reflection in the mirror, artist Deborah Kass sees what the world sees—a middle-aged woman with, as those from a generation past might put it, “the map of Jerusalem all over her face.” Surveying her 30-year career, she sees what she hopes art historians might see—a record of what she was thinking when she created her most notable bodies of work: The Art History Paintings (1989-1992), The Warhol Project (1992-2000) and feel good paintings for feel bad times (2002-present). Growing up, Kass says she never saw herself in the images that flickered in black and white on the family’s TV screen or loomed larger than life in movie theaters or triumphantly adorned museum walls. As a young Jewish girl living in Brooklyn, she understood she wasn’t alone in the world; all she had to do was walk down the streets of her neighborhood to feel a sense of belonging. That warm feeling of community, however, always gave way to a palpable void whenever she ventured too far from home. Take, for example, the first time Kass, then a middle-schooler, explored the Museum of Modern Art and was left to wonder, “What does this have to do with me?” Still, she fell in love with art. Then she fell for Barbra. Streisand, of course. “I had never seen a movie star that looked like Barbra, which is to say that looked like me and everyone I knew,” she says. It was a defining moment, the first time Kass experienced her own presence in pop culture. Starting October 27, The Andy Warhol Museum will host Deborah Kass: Before and Happily Ever After, a mid-career retrospective that explores that very intersection of pop culture, art history, and the self. The show is a bit of a homecoming for Kass, who earned her BFA in painting at Carnegie Mellon University in 1974. (Kass has said, “Warhol went there—so I went there.”) Eric Shiner, director of The Warhol, sees Kass as “one of the great American painters.” Her obsession with pop culture makes her work the ideal subject for the museum—especially considering what Kass calls her decade-long collaboration with Warhol. Starting in 1992, she stunned the art world by appropriating the work of the Pop genius of appropriation himself, replacing the famous faces in Warhol’s paintings for a contingent of her own heroes, among them Gertrude Stein, Sandy Koufax, and of course Streisand, the subject of The Jewish Jackie Series. For Kass, the work addressed a missing part of the multicultural dialogue: Jewishness. Given the Holocaust, she found the omission “alarming.” Her Warholesque paintings of Streisand in Yeshiva drag from the film Yentl, titled My Elvis, highlighted yet another side of the artist: her genre- and gender-bending sensibility. Shiner acknowledges that Kass’ initial forays into the art world were seldom greeted with enthusiasm. “Feminist artists like Deborah, who have that much drive, that much passion, have definitely been held back,” says Shiner, noting that she was often dismissed by critics and overlooked by the public. Although times have changed (perhaps not quite as much as we think), time certainly has not changed Kass. “Age has not mellowed her, oh no,” Shiner says. “She just turned 60 and she seems to have a now-or-never mentality. She takes no prisoners. She’s waited decades to be a star.”

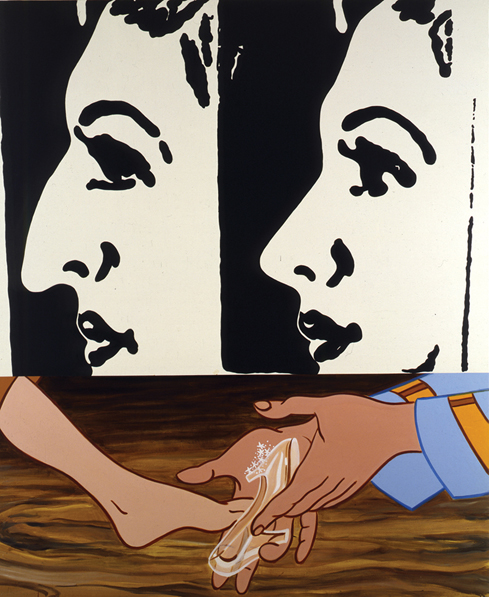

Ironically, Kass’ career is expanding, in part, by taking a look back. Peering through the lens of feminism, her series of art history paintings is about mixing and matching images from historic art and pop culture. “They’re not particularly personal,” she says, “but more mid-’80s academic.” Not surprisingly, though, they pack a punch. Her 1991 painting, Before and Happily Ever After, couples Warhol’s take on an ad for a nose job juxtaposed with a cartoon of Cinderella slipping her foot into that (in)famous glass slipper. Kass’ work will be featured in Regarding Warhol, Sixty Artists, Fifty Years, a major exhibition examining the influence of Warhol on contemporary art, which opens at the Metropolitan Museum of Art this September and will travel to The Warhol next February. Today, she’s sampling lyrics—“C’mon Get Happy” and “Let the Sun Shine In”—from Broadway and the Great American Songbook, placing them front and center on vibrantly colorful canvases. “These are my most emotional paintings ever,” she asserts. Looking at “Daddy, I would Love to Dance,” she explains that it is the female emotional epiphany of A Chorus Line. It’s Kass talking to history, talking to her own father and remembering her feet on his feet, dancing in the living room. It’s bittersweet. Sentimental. Even nostalgic. “What I’m nostalgic for is America’s greatness,” says Kass. “Popular music, movies, and post-war painting were some of our greatest cultural achievements and exports. They did more good for this country than any war. “Culture, high and low, is what made the rest of the world want to come here or be like us. So I am celebrating it.”

|

Ripped from the Headlines · The Advent of Modern Global · Drilling for Data · Perspective: Making Museums Matter · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Robert Marshall · Science & Nature: Women’s Work · First Person: A Feathered Face of Forest Fragmentation · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |