|

|||||||||||||||||

|

From the Headlines

Before cable TV and the Internet, people got their news—and their gossip— from newspapers and magazines. Andy Warhol devoured them, then elevated them to art.

“As the huckster’s wagon went its lazy way through Oakland and Homestead, Andy did something besides dish out vegetables and try to keep children from under the wheels,” reads The Pittsburgh Press story. “He set down a series of pen-and-ink sketches that show the vagaries of everything from the idle rich to the scrambling poor.” The clip includes a photograph of the budding artist and a reproduction of one of his drawings. It also marks Warhol’s first brush with the media and the recognition that often comes along with its headlines. The story’s significance “wasn’t so much that he won a prize, it’s that he got his picture in the paper,” says Matt Wrbican, chief archivist at The Andy Warhol Museum. “Who knows? Maybe that’s when he began to think that he wanted to be famous.” Current events and celebrity gossip would prove to be career-long obsessions and rich sources of inspiration for the future Pop artist, as Warhol transformed the grubby world of daily news into art. A new and much-talked about exhibition, Warhol: Headlines, presents nearly 80 of these headline-themed works, almost half of which are on view for the first time. Opening at The Warhol on October 14, the show debuted with great fanfare last September at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and has since appeared in Frankfurt’s Museum für Moderne Kunst and Rome’s Galleria nazionale d’arte moderna. Organized by the National Gallery in association with The Warhol, the exhibition spans Warhol’s prolific career, from the 1950s until his death in 1987. Along with the expected canvases and signature silkscreens, it features clips from his movies, audio from an LP, and a glimpse of the headline maker himself, co-hosting the 1983 cable show Andy Warhol’s TV. The real scoop is that many of the works appear alongside the news stories that inspired them—in several cases, for the first time. “You’ll have the source material close enough to the painting that you can make a comparison,” explains Wrbican, revealing a new window into Warhol’s role as both editor and author. News as ArtObsessively scouring the supermarket tabloids and mainstream dailies alike, Warhol was “a complete news junkie,” says exhibition curator Molly Donovan, an associate curator at the National Gallery. By tracing the artist’s use of headlines, she adds, we get a fresh perspective on his creative process. “It seems like a lot of Warhol’s themes have been exhausted, and this one hasn’t,” says Donovan. “I really followed his breadcrumbs in defining the body of work.” Warhol was “a complete news junkie.”

- Molly Donovan, curator of Warhol: Headlines

The earliest examples date from the mid-1950s, when the artist made his living as a well-known commercial illustrator in New York City. As his hand-drawn advertisements for the shoemakers I. Miller & Sons began appearing regularly in The New York Times and other big names in the news business, Warhol quickly discovered that journalism and advertising had a lot in common: They both had something to sell, and to survive, they both had to keep the public’s attention. In drawings such as Princton Leader (1956) and National Ennguirer (1958), he sketched loose representations of newsprint using ballpoint pen on paper, often with playful alterations of the source material, including obvious misspellings. In a drawing of a headline about a cruise ship hijacked in the Caribbean, 900 passengers became 900,000. By the 1960s, Warhol began applying a new method to his work, and on a grand scale using an opaque projector. The inspiration for Warhol: Headlines—a pivotal work based on headlines ripped from the cover of the November 3, 1961 edition of the New York Post—demonstrates this evolving technique. In gigantic type, the Post’s cover story declared “A Boy for Meg,” marking the birth of a first child to Princess Margaret of Britain, a then household name who’s shown smiling. Warhol’s initial artwork, a 1961 painting sketched in casein and crayon, includes rough impressions of the paper’s page layout—inflated on a massive canvas some 6 feet tall. For the second iteration, completed the following year, he used oil and egg emulsion, rendering with near-precision all but the finest print and nuanced portraits of “Meg” and Frank Sinatra, whose much smaller mug ran across the top of the cover.

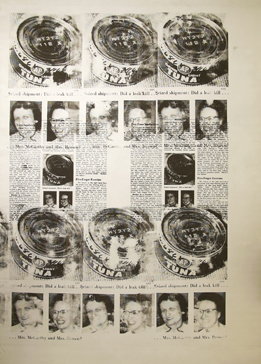

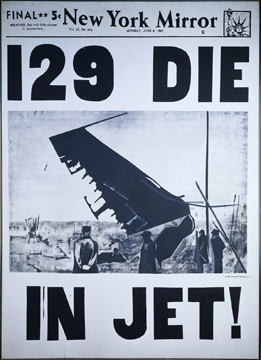

“The second ‘Meg’ painting is one of four hand-painted headline canvases that really launched Warhol’s major effort in treating the headline news,” notes Donovan, providing an evocative glimpse into his defining obsessions with portraiture, celebrity, mass culture, and disasters. “By enlarging the front page of the tabloid source on which it’s based, this painting signifies the immediacy Warhol conveyed in his art and tells us that something as mundane as the daily newspaper can indeed be grand.” Another painting from that period shouts “129 Die in Jet!” One of Warhol’s earliest works centered on death and disaster, the painting builds upon the New York Mirror’s coverage of a plane crash at Orly Airport in Paris, enlarging the already imposing headline and photograph of the tattered wreckage on a massive 100-by 72-inch canvas. Not long after, Warhol experimented with another method: silkscreening. It allowed the master manipulator to repeat images over and over, more fully embodying the mechanical reproduction of the printing press, adding perhaps an additional critique of his source material.

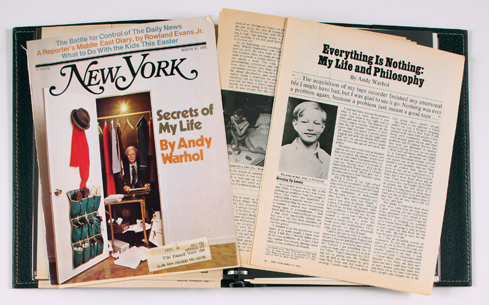

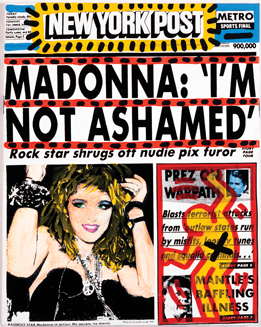

From silkscreens, Warhol: Headlines follows the artist into photography and new media, tracing his nose for news through film and video. Several of Warhol’s famous Screen Tests—four-minute, silent film portraits—show subjects doing nothing more than reading the newspaper. Late in his career, the use of the day’s hottest news remained a thread in Warhol’s near-constant production. In 1985, he collaborated with friend Keith Haring on a series of paintings based on the media hysteria over nude photos of pop star Madonna. These artworks form only one layer of the exhibit, says Donovan; the other, not surprisingly, is biographical. Scrapbooking for SuperstarsAt The Warhol, towering gray shelves on mechanical tracks house the artist’s massive archives, estimated at a half a million items. Taking a black binder from one of the shelves, Wrbican carefully pages through a scrapbook of press clippings, one of 34 collected over decades by Warhol and his staff at The Factory, his New York studio. Wrbican points out a few favorites, including a 1966 headline that reads, “Andy Warhol Interviews Bay Times Reporter,” from a high school’s student newspaper. “He preferred being interviewed by really young people,” says Wrbican. “He liked their freshness and uninhibited qualities—they weren’t as stilted as a professional journalist.”

In addition to following current events, “Warhol obsessively collected all news about himself,” notes Wrbican. Hardly a vanity collection, the scrapbooks include negative press, relatively minor mentions in gossip and society columns, along with ads for his 1960s “Exploding Plastic Inevitable” multimedia shows, events Warhol organized featuring musical and dance performances, and screenings of his films. Rather than hiring a clipping service, Warhol relied on friends and associates to collect his media coverage. He offered a small bounty, says Wrbican: “If they brought a clipping in, Warhol would pay them 50 cents or a dollar—which at that time was maybe a little more than a cup of coffee.”

In addition to the scrapbooks, the archives include countless examples of Warhol’s insatiable appetite for news and gossip, including stacks of newspapers he would bring back from his travels. The Pittsburgh show will also include the contents of one of Warhol’s famed Time Capsules from the late 1970s, which is chock full of New York tabloids. Even in photographs, Wrbican says, “Warhol usually has a newspaper in his hand, or one is nearby.” He notes one recently discovered series of black-and-white images from the 1980s that show Warhol getting a pedicure. “He’s sitting in this little salon, with his shoe and sock off, and sure enough there’s a copy of the New York Post lying next to him.” A matter of Life and DeathWarhol’s obsession with the media and fame also had a tragic side. Most notably, he made the front pages of the tabloids in 1968 when he was shot and nearly killed by actress Valerie Solanas. Toward the end of his life, too, he was the subject of negative press; Wrbican describes one such piece by Robert Hughes in The New York Review of Books as “a hatchet job.” Warhol’s life and work are inextricably linked,” adds Donovan.“They’re really one and the same; you cannot separate them. He wanted to be famous, he wanted to be in the headlines, and of course he did, tragically, end up in the headlines.” While newspapers are readily accessible, news headlines lie beyond the reach of most people. Unlike Warhol’s early sketches of daily life in Pittsburgh, they chronicle extraordinary events, unusual experiences, and larger-than-life individuals. And for news hounds like Warhol, as well as casual consumers, they exert a paradoxical attraction. “[Warhol] was an artist who chronicled his time, more than any other.”

- Molly Donovan, curator of Warhol: HeadlinesOn one hand, says Donovan, “there’s our desire to be in the headlines—if it’s good news.” On the other, “if you’re reading about the tragedy, you didn’t suffer the tragedy,” she says, which can be “affirming in a basic human way.”

Taking the ephemeral news of the day, Warhol “makes it monumental by enlarging it and turning it into art,” says Donovan. “He was an artist who chronicled his time, more than any other.”

|

|||||||||||||||||

The Advent of Modern Global · Drilling for Data · Perspective: Making Museums Matter · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Robert Marshall · Science & Nature: Women’s Work · Artistic License: Personal Pop · First Person: A Feathered Face of Forest Fragmentation · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |