|

||||

|

Hip to Be Square

Nearly everyone knows Piet Mondrian’s grid-like signature style, even if you don’t know you know it: black vertical and horizontal lines set against stark white backgrounds checkered with blocks of primary colors. It’s a revolutionary trademark so famously copied, it’s even appeared on hotels and spring fashions. So it’s the Dutch painter’s early works, on view at The Warhol for the first time in Pittsburgh, that are likely to surprise, peeling back the curtain on a pioneering modernistwho was much more than a prim technician. These lesser-known works are the focus of Piet (Mondrian) in Pittsburgh and help lay bare Mondrian’s journey to abstraction. His was a step-by-step evolution labeled by the New York Times as “one of the thrilling tales in the history of modern art.” The exhibition features 24 of the artist’s masterwork paintings, from early landscapes such as The Red Cloud, painted in 1907, to the more widely-known Composition with Blue, Red and Yellow completed 30 years later. The paintings were culled from all the great Dutch public collections, including works from the Stedelijk Museum, Gemeentemuseum in The Hague, The Boijmans van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam, and the Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, and many have never before been on view in the United States. “It’s an incredible opportunity, for the first time in Pittsburgh, to see work of this great modernist painter of the 20th century, and it probably won’t happen again,” says Tom Sokolowski, director of The Warhol. The exhibition was conceived as part of an exchange between The Warhol and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Last fall, Other Voices, Other Rooms: Andy Warhol Film & Video opened to great acclaim in Holland, with most work on loan from The Warhol. In exchange, Sokolowski brokered a trade, and in partnership with Stedelijk Museum Director Gjis van Tuyl, imagined a show that would otherwise never have made it to Pittsburgh. Because Mondrian’s early works are not widely collected in the United States, exhibitions highlighting the whole of his career have been limited. “That’s why this exhibition is so precious,” says Ting Chang, assistant professor of Art History at Carnegie Mellon University, who as a graduate student studied under late art historian and Mondrian expert Robert P. Welsh.

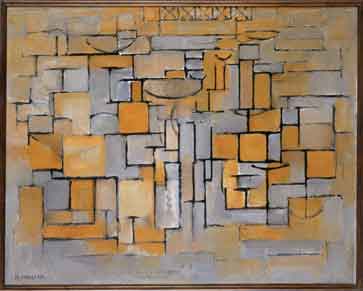

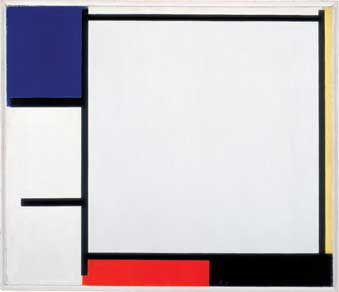

GRAPPLING WITH A NEW WORLDMondrian came from an artistic family who painted, sketched, and made music. He studied art and began his career as a schoolteacher, while practicing his own painting after hours. Not long afterward, he moved to Amsterdam, winning a scholarship to study painting at the Royal Academy, where he supported himself by giving private lessons, copying museum works, making scientific drawings, and occasionally selling a landscape painting. His earliest works were impressionistic landscapes of his homeland, and in crafting windmills, fields, and rivers Mondrian filled canvases with the vivid colors being used by his contemporaries in France.Shortly after the turn of the century in 1908, he joined a theosophy movement (a religious movement founded in New York in 1875, incorporating chiefly Buddhist and Brahmanic theories) that would become central to his life and work. He moved briefly to Paris where he was attracted to the geometric forms of Cubist painters Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. At the outbreak of World War I, he was in Holland visiting his ill father and would stay there until the war’s end in 1919.  Piet Mondrian, Tableau No.3: Composition in Oval, 1913, Oil on Canvas, Collection of Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. © 2008 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust c/o HCR International VirginiaDuring these years, he strove to define, both in practice and theory, his views on art, heavily influenced by his new beliefs. In a 1914 letter, he wrote, “I construct lines and color combinations on a flat surface, in order to express general beauty with the utmost awareness. …I want to come as close as possible to the truth and abstract everything from that.” As part of a new generation seeking a new way to understand a troubled, frenetic world, and believing that Analytical Cubism did not go far enough in representing pure reality, Mondrian developed his own vocabulary known as Neo-plasticism—for which he is best known today—through a series of experiments and stylistic movements. “On the verge of World War I, people were making very grand, heroic statements about their country and the valor of the young men who went to fight,” says Sokolwski. “Then there was a war with new kinds of horrible bombs, young men who went to fight didn’t come back, and people came to think of God and country differently. It was at this time that Mondrian’s painting became only about painting, not about God, but simply about the juxtaposition of form and beauty. It’s one of the reasons people turned to abstraction—looking at art for art’s sake.” BRANCHING OUTMondrian famously painted a Chrysanthemum, in all its forms; he first painted it at its full maturation and then as it decayed and died. “He believed you could get at some universal, spiritual quality through any one thing,” adds Chang. “So he didn’t have to paint a whole forest, just one tree. The idea was, through a kind of acuity or sensitivity, you could see the truth beneath the appearance.”In this vein, Piet (Mondrian) in Pittsburgh traces the evolution of trees as depicted by the modernist’s boldly colored representational works. It’s in Mondrian’s Cubist paintings of trees, facades, and rooftops that one can see him pushing the transitional images further and further toward abstraction. Take, for example, his work Evening; Red Tree where the subject is still very much recognizable against a rich, dark background, its trunk curved to the right and overshadowed by its wild, sprouting branches. Just one and two years later, respectively, in The Grey Tree and The Trees (recognizable to Pittsburghers as on loan from Carnegie Museum of Art), the forces of growth can no longer be restrained and the tree is no longer instantly recognizable. “I see it as moving in line,” says Chang. “If you look at the trees and the flowing branches, it’s a series of paring down. He withdraws or subtracts, so the curves are eliminated, and forms the plus and minus series that eventually becomes the later work that we know well.” Mondrian also moves from a Cubist color palette of earth tones and blues and grays toward the purity of his later works in the 1930s and 1940s, where his paintings are reduced to three primary colors, such as in his breakthrough work, Composition with Yellow, Red, Black, Blue and Gray (1920), his first true Neo-Plastic painting. A LITTLE GOES A LONG WAYBy changing the placement of a color or the thickness of a line, Mondrian learned to achieve astounding variety within a single format. He tinkered, again and again.“It’s like creating the perfect marinara sauce,” says Sokolowski. “Add the perfect mix of this and that, and maybe perfect never happens, but you’re always in pursuit of it.” Because Mondrian’s abstract art consists of black grids and primary color blocks on a white background, at a glance it can seem simplistic. But his grid-work paintings exemplify the true contradiction of modern art in that the simplest-looking work can be among the most complex, both in what it took to achieve it and in the experience it offers. As much as any artist in history, Mondrian has suffered from the effects of distorting reproductions, which can reduce work to decoration. Seeing the paintings up close changes that perspective, when the delicacy of the work is realized. He certainly did a lot with a little, and labored over each work. No two whites side-by-side are the same, and he obsessively painted over lines and employed masking tape, so there’s repetition but no two paintings that are the same.  Piet Mondrian, Composition with Blue, Yellow, Red, Black and Grey, 1922, Oil on Canvas, Collection of Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. © 2008 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust c/o HCR International VirginiaIn 1940, Mondrian fled Europe and the looming second World War for New York City, where he enjoyed much of his success. For his Big Apple debut, he re-painted 11 of his works to give them “more boogie-woogie,” as he called it. The black lines in his paintings were replaced with color lines and lines formed blocks of color. In Victory Boogie Woogie, the last before his death in 1944, small blocks of color dance all over the surface of the painting. “If one’s only frame of reference is his late works, one might think that he started painting in the very beginning from that abstract way,” explains Chang, “and this show will correct that view, because, historically, it wasn’t possible. He couldn’t have painted a Broadway Boogie Woogie in 1900. He couldn’t have done it in 1910. No one was doing it. It wouldn’t have been accepted as painting. So, in a way, this show puts the history back to his career.” |

||||

Celebrating the Mark that Makes Us Human · Voices From Mars · American Doggedness and the Carnegie International · Clash of the “Tyrant Lizards” · Special Supplement: Thanks to Our Donors · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Face Time: Sam Taylor · About Town: Robotic Wonder · Field Trip: Red Hot Find · Science & Nature: Ready, Set, Go! Sports Works 2.0 · Artistic License: Kinetic Energy · Another Look: Section of Mollusks

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |