Summer 2008

Summer 2008|

In a 20-year search that took him from the fossil collections at Yale to the thick brush behind a Mississippi truck stop, paleontologist Chris Beard, aided by a team of collaborators, has overturned prevailing ideas about ancient primate expansion.

|

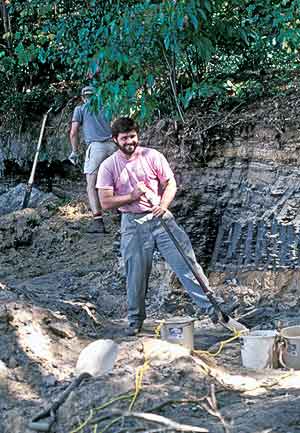

Red Hot Find

Chris Beard rummaged through a stash of fossils buried in the collections of the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University. The then up-and-coming young paleontologist opened drawer after drawer, hunting for specimens that might help with his doctoral research on primate evolution. Chris Beard rummaged through a stash of fossils buried in the collections of the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University. The then up-and-coming young paleontologist opened drawer after drawer, hunting for specimens that might help with his doctoral research on primate evolution.That’s when he stumbled on a dozen or so fossil mammal teeth, donated years earlier by an amateur collector and quickly forgotten. Beard was baffled by the label on the teeth: Eocene mammals from Mississippi. “I was already more or less an expert on Eocene mammals, and I had never heard of fossil mammals from that time period in Mississippi,” recalls Beard, the Mary R. Dawson Chair of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. When Beard noticed that one of the fossil specimens belonged to a small primate, he knew he was really onto something. It was the late 1980s, and Beard was a Johns Hopkins University graduate student on a research trip to Yale. He soon realized that, if the tag was correct, these specimens could illuminate a pivotal interval of time in a part of the world—the southeastern United States—that was previously a blank slate on the map of early mammal evolution. Intrigued, Beard borrowed the fossils and continued to study them after joining the scientific staff of Carnegie Museums in 1989. The following spring, with the help of the amateur scientist who had originally donated the fossils to Yale, Beard tracked the origin of the ancient teeth to a sandstone outcrop just outside the town of Meridian in east-central Mississippi. The fossil site was concealed in the pine thicket behind a popular greasy spoon called the Red Hot Truck Stop, which only recently was leveled to build a Wal-Mart Superstore. Armed with picks and shovels, Beard and a team of Carnegie volunteers spent a backbreaking week at the site, excavating an inch-thick layer of the embankment, uncovering mostly shark teeth, mollusk shells, and other marine specimens. Yet for every thousand shark teeth they unearthed, another fossil mammal appeared. “Out there you are basically on the cutting edge of science since you never know what’s going to show up,” says David Dockery, chief of the surface geology division of the Mississippi Office of Geology, a close collaborator in Beard’s research. The researchers soon exchanged their hand tools for a backhoe to reach the fossil-rich sandstone layer as it plunged deep underground. They sieved each load of excavated sediment in the adjacent stream, a slow, laborious process much like panning for gold. And, yes, they finally hit pay dirt in the form of additional fossil mammals, each one more precious for its scientific content than gold. But it would take years to figure out exactly what the Mississippi fossils meant. Acrobatic Continent HopperOnce back in Pittsburgh, Beard spent hour after hour at the microscope, picking out fossil teeth no bigger than rice grains from his sand samples and carefully studying his bounty. Finally, after nearly two decades of research at the Red Hot site, Beard and his colleagues concluded that the primate fossils came from a wee gremlin-like creature that weighed no more than a heaping tablespoon of sugar. They named the extinct species Teilhardina magnoliana in honor of its discovery in the Magnolia State. Teilhardina was an acrobatic leaper and proficient climber that made its home in subtropical forests, surviving on insects, fruits, sap, and gum. It probably looked like a hybrid of the big-eyed tarsiers of Southeast Asia and a small monkey. To figure out the age of the fossils, Beard linked known changes in prehistoric sea levels to the patterns of erosion they etched in the sediments. Through this method, called sequence stratigraphy, he confirmed the value of the treasure he chanced upon as a graduate student nearly 20 years ago: the primate fossils dated back 55.8 million years to the very beginning of the Eocene epoch. It was a period of rapid global warming when North America was much hotter and wetter than today, allowing primates to live comfortably along what was then the Gulf Coast. At this ice-free time, a rapid drop in sea level also occurred as drifting continents altered the volume of the ocean basins. Until this year, scientists thought that primates made their way to this continent from Asia through Europe, migrating into North America across a narrow land bridge exposed by these falling sea levels. But Beard was surprised to learn from the record of ancient fluctuations in sea level preserved in his sediments that Teilhardina already inhabited the Mississippi coastline before the sea level fell. This discovery makes his fossils about 30,000 years older than other early primates found in the Bighorn Basin of Wyoming and in Belgium. And it suggests that primates instead came from Asia to North America through a passage connecting Siberia to Alaska that already existed before sea level fell, rather than moving westerly, as previously believed. “We knew it was an important site, but we had no idea just how important it was until it became apparent that this locality occurs at a critical moment of geologic time, right before sea level fell,” says Beard. He reported his findings this past March in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The study completely turns around prevailing ideas about ancient primate expansion and stands as “a big triumph” of his career, Beard says. Not a small statement coming from a scientist who won a prestigious MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant in 2000. Still, some paleontologists argue that Beard needs to verify the age of his fossils using another method that dates materials by measuring the ratios of the carbon isotopes they contain. Later this year, Beard will return to Red Hot to try to do just that. “I will do the carbon isotopes to get the critics off my back,” Beard says. “But I’m certainly very confident that our original interpretation will hold up.” |

Also in this issue:

Celebrating the Mark that Makes Us Human · Voices From Mars · American Doggedness and the Carnegie International · Clash of the “Tyrant Lizards” · Hip to Be Square · Special Supplement: Thanks to Our Donors · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Face Time: Sam Taylor · About Town: Robotic Wonder · Science & Nature: Ready, Set, Go! Sports Works 2.0 · Artistic License: Kinetic Energy · Another Look: Section of Mollusks

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |