Summer 2008

Summer 2008|

“Looking at, thinking about, and talking over art is a great social privilege—one that visitors to the Carnegie International, and the museum in general, have enjoyed for more than a century.”

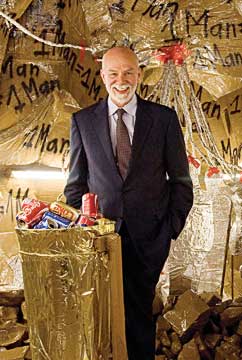

Richard Armstrong inside Thomas Hirschhorn’s Cavemanman; the installation invites Life on Mars visitors to crawl inside—shoes off—and explore. |

Not a collector himself, Carnegie and his advisors reasoned that an annual exhibition of European and American painting, organized by the museum’s Department of Fine Arts, could assemble a chronological collection. Within a few years the Annual became an eagerly anticipated cultural event, one that Carnegie likened to “the Salon for France or the Academy for Britain.” Ably overseen by the director John Beatty, himself an artist, the show gained stature and assumed its destiny as the source for a collection of “the old masters of tomorrow.” Of course, tomorrows have a way of changing, and world events, particularly wars and economic downturns, shaped the annual exhibition that came to be known as the Carnegie International. The 1958 show, presented to help celebrate the city’s bicentennial, featured new directions in contemporary art—memorably and to many visitors’ discomfort. From it came many of the collections’ mid-century landmarks, as well as the monumental mobile, Pittsburgh, that graces Pittsburgh International Airport. As planning and construction for the Sarah Scaife Galleries progressed in the late 1960s until their inauguration in 1974, the Carnegie Internationals reflected both an increasingly global art world and a variety of new media for art. The 1979 show, juxtaposing Eduardo Chillida’s sculpture with Willem de Kooning’s paintings, constituted a rich view of work by two Expressionist masters. The heightened interest in European art that enlivened the 1980s, coupled with a new generation of artists—many of them indebted to Andy Warhol—underlay the success of the Internationals of that era. More recently, the show has widened its geographic focus and introduced to American audiences the work of artists on the brink of worldwide recognition. As always, the exhibition offers a window onto new views. This year, for the first time in its history, the Carnegie International bears a specific title: Life on Mars, which can be read alternately as a provocation or as metaphorical encapsulation of curator Douglas Fogle’s vision and decisions. Douglas poses a rhetorical question: Are we alone in the Universe? His query has many answers and many implications that we will ponder over the course of the exhibition and into the future. Looking at, thinking about, and talking over art is a great social privilege—one that visitors to the Carnegie International, and the museum in general, have enjoyed for more than a century. Join in and see for yourself. Richard Armstrong The Henry J. Heinz II Director Carnegie Museum of Art |

Also in this issue:

Celebrating the Mark that Makes Us Human · Voices From Mars · American Doggedness and the Carnegie International · Clash of the “Tyrant Lizards” · Hip to Be Square · Special Supplement: Thanks to Our Donors · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Face Time: Sam Taylor · About Town: Robotic Wonder · Field Trip: Red Hot Find · Science & Nature: Ready, Set, Go! Sports Works 2.0 · Artistic License: Kinetic Energy · Another Look: Section of Mollusks

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |