Summer 2008

|

||||||

|

|

Celebrating the Mark that Makes Us Human

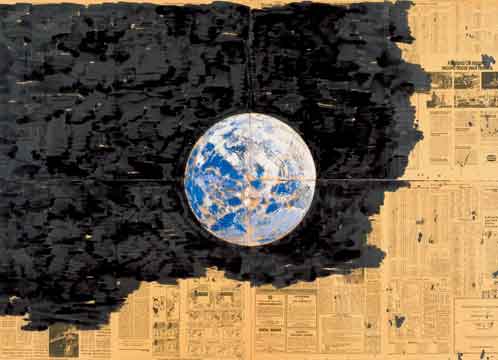

Forty artists from 17 countries leave their marks on Pittsburgh and the world of art with their contributions to the 2008 Carnegie International. For curator Douglas Fogle, there’s a distinct connection between the artists he chose for Life On Mars, the 2008 Carnegie International, and some rather disparate forebears. The Lascaux cave painters, who left their prehistoric marks in the now-famous cave drawings discovered in southwestern France, serve as one common bond. Another: Carl Sagan’s “Pioneer plaques,” attached to the Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 spacecrafts as a pictorial explanation of humanity to whomever—or whatever—might someday find them.It’s not that Life On Mars features artists intent on anachronism or science fiction. Rather, as Fogle explains, the show’s 40 artists from 17 countries all share a mark—the mark of humanity. “The basic elements of art-making are human,” says Fogle. “They’re actually what makes us human—our ability to make a mark that has some intelligibility.” Take this year’s winner of the Carnegie Prize, Vija Celmins. When the Latvian-born New York artist sets her brush to canvas to create one of her numerous Night Sky paintings, it seems that she can tame her subject’s humbling infinity by repeated, lovingly rendered marks. Richard Armstrong, The Henry J. Heinz II Director of Carnegie Museum of Art, sees her strength in that repetition. “Celmins is one of the pillars of contemporary art anywhere in the world,” says Armstrong. “She’s been very focused on a limited subject matter for a long time, and has treated that subject with tremendous imagination.” That mortal hand, the connection with our own humanness, is present in so many of Life On Mars’ works. Be it Richard Wright’s ephemeral gallery drawings, or the gathered materials that serve as Mark Bradford’s canvases; the beautiful and introspective installations of Rivane Neuenschwander and Ranjani Shettar; or Thomas Hirschhorn’s bold and imposing environment, Cavemanman. The committee of advisors Fogle consulted with when creating Life On Mars included some of the most important thinkers about theory and practice in contemporary art CARNEGIE magazine asked these advisors—Daniel Birnbaum, Richard Flood, Eungie Joo, and Chus Martinez—for their own take on Life On Mars by talking about the theme as it’s represented in the disparate works of some of the artists.  Paul Thek, American, 1933–1988; Untitled (Earth Drawing I), c. 1974, acrylic on four sheets of newspaper; Collection of Robert Wilson, New York, The Estate of George Paul Thek. Courtesy of Alexander and Bonin, New York.In a very tangible way, American artist Paul Thek’s drawings and paintings, done on copies of the International Herald-Tribune while living in self-imposed exile in Europe, are the beginnings of Life On Mars. While Thek died 20 years ago, as advisory committee members Richard Flood and Daniel Birnbaum explain, his influence is only now approaching its potential. Richard Flood: There is a cult of Paul Thek—a cult of which I am a happy member. I think Paul is, in many ways, one of the most prescient artists of his time; in terms of what he made and how he made it, he’s remarkably up-to-date. Looking at these drawings, there’s something so beautiful and so profoundly sad about them at the same time. The one with the see-saw—I find it incredibly moving, and it’s just because the playground is empty; the sky is grey; the birds—are they threatening, or benign? It’s a state of suspended ambiguity that I think Paul managed to capture better than any other artist I can think of. Daniel Birnbaum: For this show, I know that Douglas Fogle was very interested in a low-tech, hand-crafted feel, unpretentious but still visionary in what the artist tries to say. It’s interesting, these artists who, even being dead for years, can keep being productive, not only because they’re ‘important’ in some kind of Picasso way but because they’re artists’ artists. People re-read them, and other artists look upon the work and continue to work with them. Another artist in this show, Mike Kelley (whose colorful, glowing installation is on the ground floor of the Hall of Sculpture), is also a great writer, and has been very important in looking again at certain artists who maybe aren’t in the ‘big book’ of art in the 20th century. Paul Thek is perhaps now in that ‘big book,’ but he certainly wasn’t. He was the kind of artist who was a little bit of a secret.  Haegue Yang, Korean, b. 1971; Three Kinds, 2008, mixed media; Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin. Commissioned by 2008 Carnegie International.In Haegue Yang’s installation, Three Kinds, the Korean artist uses a room filled with light and color, separated by Venetian blinds cut into various shapes to create a new space and a new experience of space. Yang’s interest in the commonplace, as Chus Martinez and Eungie Joo explain, is a central element in Life On Mars. Eungie Joo: I think Yang’s work is interesting in the way it uses lighting and other mechanized sensorial experience to take you to a memory; to the hint of something else. And I think her work ends up becoming like a reflective space. There are a lot of materials and works in this exhibition in which the scale is like that—it’s human. Chus Martinez: Yang is playing with elements that are familiar to the viewer, that even have roots in the domestic environment. It’s playing with assumptions: a very familiar material, familiar form, nothing is exceptional, yet there is something happening which has nothing to do with our real-life relationship to this material and this experience. In a very subtle way, she’s shifting things we know. It’s this kind of commonness [that asks], ‘how can we make sense in the smallest scale?’ We’re not acting on a big scale, we’re not politicians running the country, [this is] people asking themselves, ‘Do I have agency? Can I change the world?’ And I think that artists are saying that small-scale changes do matter.

German-born, London-based photographer Wolfgang Tillmans rose to prominence in the 1990s with his photographs of European youth and club culture, magazine, and fashion work. In 2000, he became the first artist born outside of Britain to win the coveted Turner Prize, and recently, his work has turned decidedly towards the abstract. But as Richard Flood and Daniel Birnbaum point out, that abstraction was always present. Richard Flood: Tillmans was doing fashion photography at the same time [that he was gaining prominence as an artist], and kind of revolutionized fashion photography. Then he began to really break it out in so many different ways, so that the whole notion of what a photograph is [changes]. How you show a photograph, how you scale it—often his smallest ones are the most heroic. And all of a sudden these incredible details are turned into abstractions. Daniel Birnbaum: Some people think that Tillmans’ work is a crossover from fashion, which is not true—it’s the other way around. He’s a photographer who wanted to use other means of communication; he likes working for magazines. Tillmans has been very much involved in not developing a language of importance. There’s something very direct and honest about everything he does, which has not stopped him from doing things that are ambitious, and that almost verge on the painterly. But he’s becoming more interested in photography as a pure medium, where you can work with chemistry and photosensitive material to make things like Freischwimmer 118. There’s no camera involved there. It’s very corporeal, visceral; like hair, but it’s not figurative. And once [that type of work] began, it became clear he’d been interested in abstract moments all along. Only now it’s become more luxurious, more pronounced. We all felt that the show is very much about humanity, and so is his work.  Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Unknown Forces, 2007 (installation view), 4-channel video; color, sound, duration variableThe winner of the first annual Fine Prize, awarded to one of the International’s emerging artists, is filmmaker and installation artist Apichatpong Weerasethakul, whose Life On Mars contribution, Unknown Forces, is a four-channel video installation with its roots in the traditions, superstitions, and religion of Weerasethakul’s home in Thailand. Chus Martinez and Eungie Joo hope that the prize-winning piece will lure audiences into the exhibition’s darker corners—and keep them there. Chus Martinez: People encounter paintings and other objects just walking through the museum. I think it’s important to stress that people spend time in these other galleries that construct the perception differently; the filmic part of the exhibition. Paul Sietsema, Sharon Lockhart, and a couple other artists in this exhibition are very productive in how they talk about boredom—the limits of what you can stand in terms of time and observation. Boredom is only boredom because you are testing the limits of what you are prepared to face. [Watching] TV, the moderator says, ‘We’ll be back in a minute,’ but in a gallery’s video room, no one is telling you what’s going to happen, or how long you should stay! Eungie Joo: With Weerasethakul’s Unknown Forces, he has four different tracks playing simultaneously. So when you first walk into the room on your right, you see two people each sitting on the back of a pickup truck, and they’re talking about the happiest time in their lives. But you can’t tell, because, one, they’re speaking in Thai. But also, the wind is so strong that it overwhelms their voices. There’s another image across from you, of a young man dancing on the back of a truck that’s driving down the highway. And then on the left, you see a mysterious object—a tent of sorts—and associated with that is a changing soundtrack, that ranges from ambient noise to a syncopated electronic disco music. But you have to go through several chapters before you can see how the experience of the images contextualized by different sounds changes your perception. To [experience] this, you have to have endurance—and faith.  The Life on Mars jury, charged with the task of selecting this year’s Carnegie and Fine Prize winners, included the Life on Mars advisory committee members and key Museum of Art leaders. Left to right, Daniel Birnbaum, Museum Director Richard Armstrong, Museum Chair Bill Hunt, Chus Martinez, Museum Board Member Lea Simonds, Richard Flood, and Eungie Joo.In creating the 55th Carnegie International, curator Douglas Fogle created an advisory committee comprised of some of the contemporary art world’s most renowned theoretical and curatorial minds. “The role of the advisors is a crucial one in helping the curator distill and expand his or her ideas,” says Richard Armstrong, The Henry J. Heinz II Director of the Carnegie Museum of Art. “This committee was especially catalytic, and had a sustained interest in Doulgas’ thinking process.” Daniel Birnbaum, Richard Flood, Eungie Joo, and Chus Martinez are widely regarded names in the art world, and their presence in the process of creating Life On Mars resonates throughout the show. Daniel Birnbaum, a native of Sweden, serves as director of the Städelschule Art Academy and Portikus Gallery in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Richard Flood is chief curator of New York City’s prestigious New Museum. He has served as curator of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and of PS1 in New York City, as director of the Barbara Gladstone Gallery, and as managing editor of Artforum. Eungie Joo is the New Museum’s director and curator of education and public programs, and previously served as director and curator of the Gallery at the Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater (REDCAT) in Los Angeles. Chus Martinez, a native of Spain, currently serves as director of the Frankfurter Kunstverein in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Previously, she was artistic director at Sala Rekalde contemporary exhibition space in Bilbao, Spain.

|

|||||

Also in this issue:

Voices From Mars · American Doggedness and the Carnegie International · Clash of the “Tyrant Lizards” · Hip to Be Square · Special Supplement: Thanks to Our Donors · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Face Time: Sam Taylor · About Town: Robotic Wonder · Field Trip: Red Hot Find · Science & Nature: Ready, Set, Go! Sports Works 2.0 · Artistic License: Kinetic Energy · Another Look: Section of Mollusks

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |