Spring 2008

|

||

|

Seeing Stars

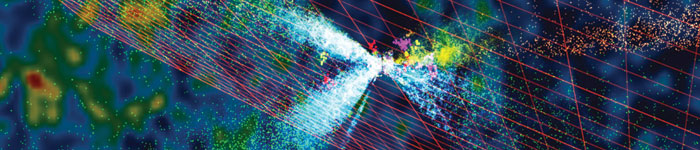

With bold new investments in its already much-lauded astronomy program, Carnegie Science Center is tapping in on the public’s fascination with the stars and outer space by providing something for everyone—from the Saturday evening stargazers to the next generation of scientists and researchers. Overhead, splotches of yellows, reds, blues, and greens pulsate like jellyfish drifting through the ocean. This is the edge of the universe—or as far out in space as humans have viewed. The colors represent background radiation from the Big Bang, 13.7 billion light years away. This spectacular display is just one result of the major facelift given to the Science Center’s already out-of-this-world astronomy program, a makeover guided by Radzilowicz and his small team of scientific and multi-media experts. A $1.7 million investment in cutting-edge technology further solidifies the program’s prominence, he says, and is fueling even greater interest from students, teachers, amateur astronomers, and university researchers engaged by the Science Center’s “astronomy academy” approach, which includes a wide variety of programming designed for a diverse audience. Come March 28-30, plenty of those curious learners—from backyard stargazers to more sophisticated amateur astronomers—are expected to converge on the North Shore facility to celebrate astronomy in an annual ritual newly dubbed Space Out! Weekend. Presented in partnership with the Amateur Astronomers Association of Pittsburgh, the University of Pittsburgh, and Carnegie Mellon University, the weekend program encourages visitors to get lost in space, learn how to navigate among the stars, try out the world’s best amateur telescopes, get clued in to the latest astronomical happenings, and get a close-up look at meteorites and moon rocks.  The Sun, the Stars, The Moon—In High DefBack inside the newly evolved Digital Dome, Frank Mancuso, one of the men behind the magic, stands in the back, pointing and clicking a mouse to power its Digital Universe database. He zooms past the galaxies closest to the edge of the universe, moving in toward the radio sphere (the distance to which escaping radio signals have traveled out into space, about 70 light years). Planets zip by. Then he nears the local galaxies, those closest to the Milky Way. Soon, the red hulk of Jupiter and the rings of Saturn indicate he’s nearing home.Exploding in big and beautiful high-definition color are real-time images of the sky directly from NASA and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, the most ambitious astronomical survey ever undertaken, which has mapped one quarter of the night sky, consisting of millions of individual objects. This technology allows visitors to see the actual universe from a comfortable seat in the upgraded Buhl Planetarium, renamed Buhl Digital Dome in the fall of 2006 to honor The Buhl Foundation’s long-term support. The Foundation gave the $1 million the Science Center needed to purchase the true state-of-the-art in planetarium technology, the definiti® full-dome video system from Sky-Scan, now installed in fewer than 10 percent of planetariums worldwide. “The power of this domed theater is that it can really take you there,” says Radzilowicz. Meaning, just about anywhere in the universe. From Pittsburgh. For instance, the Science Center’s first-ever full-dome production, A Traveler’s Guide to Mars, funded by a $400,000 grant from the Bozzone Family Foundation, brings audiences onboard a manned spaceship about to land on Mars. As the craft enters the atmosphere, two astronauts tinker with controls as sparks fly from the ship with Mars looming in the background. The scene incorporates all the elements that showcase the dome’s one-of-a-kind, put-you-there experience: artists created the ship using computer-generated imagery; NASA images of Mars show audiences the actual planet; and actors used motion-capture technology so that the animators could create astronauts that move like humans, not unlike technology that’s used in most Hollywood special-effects flicks, such as Pirates of the Caribbean, as well as popular video games. Prior to the upgrade, staff orchestrated dozens of projectors, special-effects machines, and audio equipment to create a show that covered only a portion of the 50-foot dome. Today, two projectors cast images onto the whole 50-foot dome and a show now consists of only mouse clicks. The new system projects 16 million pixels per frame, 60 frames per second. “For now, we’re at the top of the heap,” Radzilowicz says. “Few facilities have the experience or the context that we have.” The Gateway ScienceProbably more than any other kind of science, astronomy makes dreamers out of just about everyone. All it takes is one glance up on a clear night. But at the Science Center, which has long roots in astronomy that go back to the old Buhl Planetarium and Institute of Popular Science, the study of the stars often leads kids into all kinds of meaningful scientific exploration.Take 16-year-old Maria McBride. She lost her first tooth while gazing up at the stars at the Science Center. Today, her goal is to get a much closer glimpse of the night sky. “I want to be the first woman on the Moon,” says McBride. “The honors program made me sure that I wanted to be an astronaut, after exploring all types of careers.” Part of McBride’s honors program—a fourth-grade science class, by the way—included a trip to the Science Center for a simulated space mission, with half the class charged with mission control and the other half command of the ship. “The Science Center in general has so many different kinds of things to engage students,” notes McBride’s former fourth grade science teacher, Nancy Bires, of Hermitage School District in Mercer County. She’s been bringing students to the Science Center for years. “You can select classes that fit specific units the students are learning, and some programs are even designed especially for your group.” As McBride prepares to apply to Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to achieve her dream, other Pittsburgh area natives who already work for NASA say the Science Center’s planetarium cultivated their own interest in space. Emsworth native Mike Fincke’s action speaks louder than words: As science officer on the 2004 International Space Station mission, Fincke chose to conduct his only live downlink at the Science Center, home of Buhl Planetarium, where as a child he explored space through planetarium shows. “That a guy from a blue-collar background like me could dream of going to space and then grow up and actually do it is an amazing thing,” says Fincke, who is scheduled to head back to space this fall in command of Expedition 18.

Left, The ominous Zeiss Model II electro-mechanical projector from the original Buhl Planetarium.Paul Stumpf, who navigates the mission to examine Saturn and its moons at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab at the California Institute of Technology, also has vivid memories of childhood trips to the original Buhl Planetarium and Institute of Popular Science. As the light would dim inside the planetarium, Stumpf recalls, “a mutant ant rose from the floor” (the old projector was pretty omnious). He knew, though, a trip through space would follow the strange creature’s arrival. And after observing the stars from the seats of the planetarium, he knew he wanted to work for NASA. Stumpf confided in his Boy Scout leader, who introduced him to volunteer opportunities at the Science Center. Over the years, the Pittsburgh native enrolled in the Science Center’s astronomy apprentice class as well as the robotics and spectroscopy programs. Not soon afterwards, he produced and narrated sky shows, such as the popular Stars Over Pittsburgh. Stumpf credits his experience programming the star shows at the planetarium for preparing him for his daily work today. As a navigator at the Jet Propulsion Lab, he selects maneuvers designed by programmers to guide mission craft to their locations. “It’s funny that when I was at Buhl Planetarium doing shows, I would talk about Cassini (the name of his current mission at NASA),” says Stumpf. “I thought it would be cool to work on it 10 years ago, and I think how cool is it that I work on it now?” Going GreenBuhl Planetarium’s laser system—which bumps to the beat of sounds as diverse as The Beatles and the B52s during laser night shows—has also been upgraded, and made “green.” The old lasers burned so hotly that they required thousands of gallons of water to keep them cool. Their replacements in the Buhl Digital Dome are small and use much less energy and create much less heat—eliminating the need for water.“This technology allows us to enter into a new way of using a planetarium,” notes Radzilowicz. One might wonder, though: Why look to the stars if the nation can’t even solve its own global warming? “You cannot be a citizen of the planet and not know what the larger picture is,” Radzilowicz counters. “Just to get your mind around global warming or evolution, you’re missing a tremendous amount of information if you don’t understand the planet’s relationship to the rest of the universe.” Almost on cue, Radzilowicz takes an elevator ride up to the roof of the building. A large metal cylinder perched on the roof’s edge houses the facility’s observatory. Inside it, a high-powered telescope provides stargazers with the only observatory within city limits. One, maybe two adults can squeeze into the tube at a time. But soon, that will all change. A recent gift in excess of $200,000 from Bob and Joan Peirce, will fund a new observatory, now in the works, and a new telescope complete with a digital video camera. So if the weather is cold or the observatory is too crowded, star gazers can enjoy spectacular views of the Big Dipper and the North Star—plus so much more—from the warmth and comfort of the Buhl Digital Dome via a live video link. The technology will also enable staff to record special or daytime astronomical events, increasing their visibility to school groups and the public. No group will be happier when the new observatory comes to be than the Amateur Astronomers Association of Pittsburgh (AAAP), whose members petitioned the city in the 1930s for the first Buhl Planetarium to be built, and who today routinely partner with Radzilowicz and company. The 530-member association, the third largest in the state and fifth nationally, holds its monthly meetings at the Science Center, and is always on hand for special astronomical happenings such as a solar eclipse. Most importantly, it shares the Science Center’s goal of fostering the next generation of star and space lovers. “Having a planetarium in Pittsburgh with an active staff creates a paramount experience for children today,” says Pete Zapadka, a longtime member of the AAAP. He goes on to explain that kids just can’t see the same night sky that he did, decades ago. Zapadka grew up north of Pittsburgh during the late 1950s, when light pollution didn’t cloud the sky. In the evenings, he says, he observed a dazzling display of the heavens. The Science Center offers the next best thing. Says Zapadka, “Technology is how we can reach kids.” Kids like Paul Stumpf and Mike Fincke. |

||

Also in this issue:

Traveling Warhol · The Art of Being Human · The Explorers Club · The Future is Now · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Face Time: Matt Wrbican · Science & Nature: A Scoop Full · Artistic License: Animal Attraction · First Person: Full Body Experience · Then & Now: The museum as classroom

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |