|

||

“I don’t want The Andy Warhol Museum to be the Andy Warhol mausoleum. If the world can’t come to Pittsburgh to see Andy Warhol, then we’ll take him to the world—wherever that might take us.” --Tom Sokolowski, director,

|

Traveling Warhol

Andy Warhol didn’t travel like the rest of us. He loved flying on the Concorde, the supersonic jet that whisked passengers from New York City to Paris in something like 13 seconds burning specially blended jet fuels refined from Liz Taylor’s perfume and Studio 54 Champagne. Sounds fabulous, doesn’t it? Then you understand why Warhol probably logged more than 45 zillion frequent flyer miles. These days, Andy Warhol still gets around. Maybe more than ever. An impressive feat for a guy who died more than 20 years ago. Right now, Warhol’s in Australia until early spring, or early autumn Down Under. Then he’s off to China—perfect timing for Beijing’s big Olympics glamfest. Andy always loved a self-consciously over-the-top bash. All right, Andy Warhol’s really not going anywhere anymore. But thanks to the efforts of the keepers of the flame at The Andy Warhol Museum, his art and vision are—practically non-stop, from Kalamazoo to Kazakhstan. And Andy’s latest travels are spreading his appeal to a new generation of fans around the globe and reaping big benefits for the museum that bears his name in his hometown of Pittsburgh.

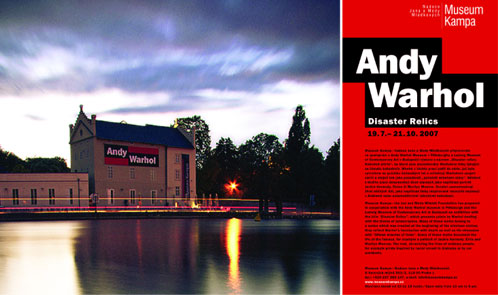

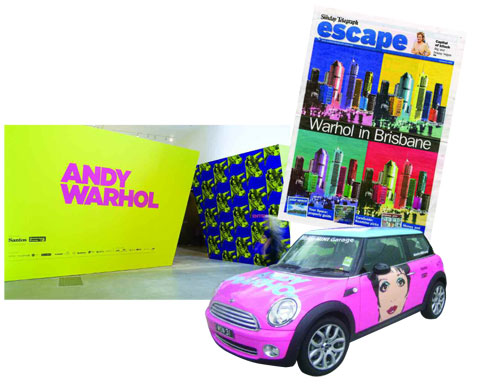

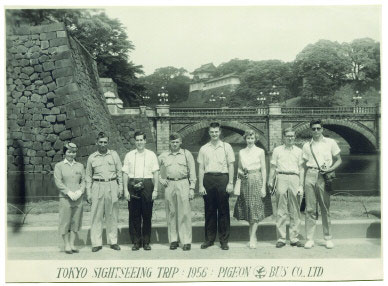

Museum Kampa in Prague, Czech Republic, showcased Warhol’s Disaster prints in 2007. Warhol’s Time Capsules continue to attract crowds all over the world.Assuming a Missionary PositionLittle boys used to “flip” baseball cards. Now they swap top-secret access codes to hack the CIA-controlled supercomputers that dictate ticket sales for Hannah Montana concerts.If young Andy Warhol ever exchanged anything with other kids during his childhood, it might have been the paintings and drawings he created in Carnegie Museum of Art’s Saturday morning art classes under the tutelage of the legendary Joseph Fitzpatrick. Today, people within the Carnegie Museums’ family still trade Andys, but on a much different level. Shortly after The Warhol opened in 1994, its staff set out on a mission—to take Andy to the world. Through a combination of in-kind trades and specially curated loaner exhibitions, works from The Warhol collection have appeared in museums and galleries on nearly every continent (not counting the Warhol’s Santa Claus Myths print, allegedly on display at the South Pole scientific research station). The museum’s first major traveling exhibition, Andy Warhol 1956-86: Mirror of His Time, went on view in Japan in 1996. (It was a fitting location: Japan was the first foreign country Warhol visited.) Today, 5.5 million people across the planet have viewed Warhol’s art, and museum director Tom Sokolowski admits that he gladly embraces the role of Warhol’s top ambassador. “When I first came here,” says Sokolowski, “I said that I liked the missionary position. If you are holding the largest collection of Warhol artwork in the world, then you have the responsibility to send that art around the world. “There used to be a feeling that people would make the pilgrimage to Pittsburgh to see Warhol,” he adds. “And we do get many visitors from many places. But they’ll never come here in the numbers that we can attract with traveling exhibitions.” Generally, people don’t dispute what Sokolowski says—especially when he has the numbers to back up his claims. In Amsterdam, Warhol’s Other Voices, Other Rooms exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum smashed projected ticket sales of 80,000 by 50 percent and twice broke daily museum attendance records during a run that ended this past January. The show provided a glimpse of Warhol’s world through his film, photography, and video. And, certainly, the Dutch got more than an eyeful. At the Queensland Art Gallery in Brisbane, Australians are currently journeying through a lifetime retrospective of more than 300 works, chronologically categorized to chart the changes in Andy’s life and art. “It wouldn’t have been possible without The Andy Warhol Museum for us to stage an exhibition of this breadth and depth,” says Suhanya Raffel, senior curator of the Australian exhibition. “Because we’re so far away, we have to look very carefully when we manage such complex loans. Our team worked closely with The Warhol staff over a four-year period.” One of the largest Warhol shows ever, the exhibition attracted 50,000 visitors in the first five weeks of a three-month stay. The trek down Warhol’s memory lane retraces his early days as a successful New York City commercial artist to his final days as the established figurehead of pop art. Crowds are still teeming in from as far as Sydney—an hour’s plane ride away. “I think Warhol is the quintessential American artist of the late 20th century who is still affecting how art is expressed in the 21st century,” Raffel notes. “There’s a real recognition that he understood how people felt about music, art, dance, film, and fashion being ways of personal expression.” “By taking Warhol to the world,” adds Sokolowski, “it’s a different way of introducing people to American culture—instead of just dumping 65,000 pairs of Nike shoes on them.”

Clockwise, from top left: Scenes from recent exhibits in Frankfurt, Germany; Seoul, Korea; and Brisbane, Australia.

Payback with a HitchOf course, when a Netherlands museum shows its gratitude for a traveling Warhol exhibition, no one really wants to see that appreciation expressed with a carpet bombing of wooden shoes. That’s where another type of trade comes into play.“It’s common in the museum world for institutions to trade exhibitions, especially for places with a concentration of one artist’s work,” says Colleen Russell Criste, The Warhol’s deputy director. “In the past, we’ve partnered with the Georgia O’Keeffe and Salvador Dali museums. Recently, we worked out a trade with the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh for the Ron Mueck exhibition. “We’ve found wonderful ways to let other museums use the Warhols they want and give our visitors here the opportunity to see other artists’ work that fits within the museum’s mission,” Criste notes. A whopper of a trade coup is the Piet Mondrian exhibition, which will arrive at The Warhol in May from the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Mondrian is a Dutch artist best known for his paintings of rectangular forms of red, yellow, blue, or black, separated by thick, black rectangular lines, and the exhibition will include many pieces that have never been seen before in the United States. “This is a huge deal for us, and for Pittsburgh. Without this kind of relationship, we wouldn’t be able to bring this exhibition to the museum,” says Criste. In some cases, Warhol trades can even benefit the other Carnegie Museums. When the National Museum of Wildlife Art borrowed Warhol’s Endangered Species collection, the Jackson Hole, Wyoming, institution sent exhibitions to both Carnegie Museum of Art and the Museum of Natural History. Money does change hands in exchange for the use of The Warhol’s collection—especially when larger museums request large amounts of art. But the best kind of payback are the rave reviews from national and international audiences and art critics, which bolster The Warhol’s image in ways money can’t buy. As Andy once quipped, “Don't pay any attention to what they write about you. Just measure it in inches.” “Touring helps legitimize Warhol’s work, the museum, and what we do here,” says Criste. “And it shows the world that our collection isn’t going to be treated as a hothouse flower.” Touring has its risks, however. Criste points out that the museum goes to great lengths to make sure its collection is well cared for and preserved. “Accidents can happen while the work is on the road and this is something we need to consider every day. We make great effort to assess and secure the conditions of where the work will be and, of course, to secure the objects themselves.”   Top, clockwise: Warhol at the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 2007; in Brisbane, Australia; and staff from The Warhol’s education department take time out of a trip to visit Russia’s Red Square.The role of caretaker is an especially important one, since everybody seems to want a piece of Warhol. “People are fascinated with Warhol,” Criste notes. “Museums exhibit his work. Galleries sell it. People collect it. Scholars study it.” And people the world over clamor to see it. So many, in fact, that the art of Andy Warhol just might be Pittsburgh’s biggest cultural export, ever. “In terms of the number of people who see a Pittsburgh product that is immediately recognizable as an international commodity, there is nothing like Andy Warhol,” says Sokolowski. “We had an exhibition in Moscow that brought in 100,000 people to see a show by Andy Warhol, a citizen of Pittsburgh, through The Andy Warhol Museum, which is part of Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh. There is no other institution in the city that brings in those kinds of numbers.” Adds Criste: “Part of Warhol’s history is tied to Pittsburgh. And this history is integrated into everything we do. In comparison, although from Pittsburgh, the content of the music performed by the touring Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra is not immersed in Pittsburgh’s history like Andy Warhol and the influences that Pittsburgh and what he learned while here had on his work. We’re kind of like what the steel industry was for Pittsburgh years ago. There’s such a demand for Warhol around the world. And we’re constantly responding to it.” When the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts began preparing for its own Fall 2008 Warhol show, titled Warhol Live, which traces the artist’s work and its relation to music, it looked to The Andy Warhol Museum to make it happen. The first-of- its-kind show focuses on everything from Warhol’s early LP cover designs in the late 1940s to ticket stubs from concerts nearly 40 years later. And most of the artwork and artifacts are from The Warhol’s collection. It’s kind of fitting, then, that the show will make an appearance at The Warhol during the summer of 2009. “The Warhol Museum is the Mecca of all things Warholian,” says Stephane Aquin, curator of contemporary art at the Montreal museum. “I would compare it to the Picasso Museum in Paris. Maybe even more so. The Picasso Museum doesn’t have the archives and richness of documentation that makes The Warhol so invaluable. If you want to do an exhibition about Warhol, you have to start with The Warhol Museum.”  Above, , Warhol’s art takes Brisbane by storm as shown on the cover of the Sunday Telegraph.Getting AndyAs Andy Warhol makes his rounds these days, it’s no surprise that it’s often among younger fans internationally. Today’s youth seem to “get” Warhol the exact same way their parents did—when their parents were 40 years younger and way more cool.When The Warhol staged a show in Russia at the turn of the millennium, Sokolowski says many people—mostly leftover Political Bureau types with thick accents and even thicker eyebrows—scoffed at the exhibition’s “disgraceful” obsession with Western consumerism. Yet, five years later, an encore show in the former Soviet Union generated a different reaction. “It was a changed world,” Sokolowski says. “Everyone seemed to be 21. There were drag queens and fabulous people running around with cell phones and lots of money who were getting Warhol.” Cross-dressing and fabulousness aside, youth will likely rule in Montreal, where under-30 types are expected to tune in in large numbers to Warhol Live. Along with creating art for dozens of record albums, Warhol “discovered” and produced the Velvet Underground, which led to a longtime friendship with Lou Reed. Over time, Warhol’s musical acquaintances elevated him to rock-star status among younger fans.

Left, Andy Warhol’s first trip abroad started in Japan.“Warhol’s work attracts youth in a trans-generational way,” says the Montreal Museum of Fine Art’s Aquin. “That’s a phenomenon that’s been going on for more than 40 years. Youth, in general, see him as someone who speaks their language. His influence goes far beyond the art world.” One anecdote of a jet-setting Warhol show might best sum up both the spirit of his work and just how far its influence travels around the globe: During a U.S. Department of State tour of more than a dozen countries in Eastern Europe and Asia, the Warhol exhibit stopped in Kazakhstan. As the delivery truck pulled up to the exhibition space, a caravan of men on camels followed behind and watched as the crew unloaded Warhol’s works to be displayed. The absolutely appropriate absurdity of the scene doesn’t escape Sokolowski. “It was a perfect example of the new world meeting the third world,” he says. “I’d hate to say that we would only send work to Paris or London or some other ‘safe’ place. I don’t want The Andy Warhol Museum to be the Andy Warhol mausoleum. If the world can’t come to Pittsburgh to see Andy Warhol, then we’ll take him to the world—wherever that might take us.” Andy, you better start packing.

|

|

The Art of Being Human · The Explorers Club · Seeing Stars · The Future is Now · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Face Time: Matt Wrbican · Science & Nature: A Scoop Full · Artistic License: Animal Attraction · First Person: Full Body Experience · Then & Now: The museum as classroom

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |