|

||||||

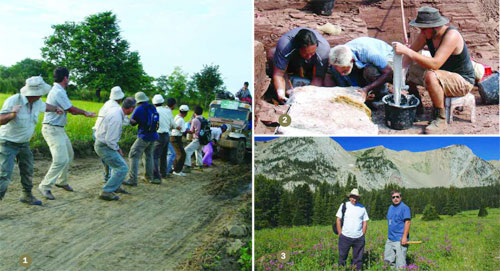

In July 2007, Mary Dawson (far right), curator emerita of vertebrate paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Natalia Rybczynski (center) of Canadian Museum of Nature, and Liz Ross found a small, carnivorous mammal in 23-million-year-old lake deposits on Devon Island, Nunavut, Canada.

|

||||||

|

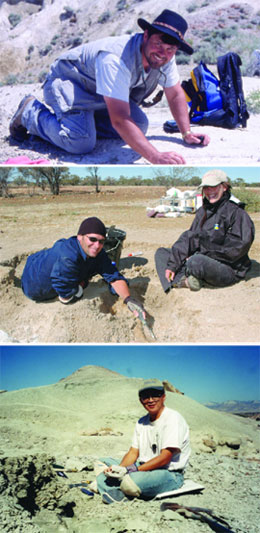

Chris Beard searches for tiny fossil mammals in the Bison Basin of central Wyoming.

|

Luo says he’s been fascinated with paleontology since his first field dig as a college student 30 years ago, when he found a piece of ancient coral embedded in limestone. “It’s inherent in human nature to think about life,” he says. “A natural history museum should be in the frontier of exploration and discovery. The understanding of life and its history and the understanding of human society and its diversity, will give meaning to human existence.”

Carnegie Museum of Natural History is prolific in doing just that. Since 2000, museum scientists have published 20 papers in the prestigious science journals Nature and Science and have been awarded 57 research grants, including nine from the National Science Foundation.

Luo is currently working on yet another ground-breaking project with fellow Museum of Natural History mammalogist John Wible. Luo and Wible are part of a National Science Foundation program called “Assembling the Tree of Life.” Along with paleontologists and biologists from around the country, the duo is trying to piece together the evolutionary tree of mammals like anteaters, kangaroos, and platypuses. “Sure, I love looking at duck-billed platypuses and possums, but my ultimate interest is looking at the big picture of their evolutionary relationships,” says Wible. “At the end of the day, we want to combine all the data from DNA and anatomy to come up with what we think of as the truth, as in, who’s related to whom.”

How we got here is the big truth driving Chris Beard, also a curator of vertebrate paleontology. Beard is a recipient of the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship (also called the “genius” grant) for his work studying the origins of primates, the order of mammals that includes all monkeys, apes—and, yes, humans. Beard’s work takes him to sites in the Gobi Desert in Inner Mongolia and rural Myanmar (formerly Burma), where he surveys fossil sites first discovered in 1913 by British scientists.

Because of Myanmar’s political isolation (a military junta has run the country since 1962), the site was largely untouched until Beard and his collaborators arrived there. “Almost no work had been done there between the 1910s and the late 1990s,” Beard says. It’s since yielded a wealth of fossils, including bones of “teeny tiny primates” the size of a shrew. “It’s kind of like breaking the sound barrier for primates, because no one ever thought they could be so small.” What propels Beard is a fascination with what fossils can tell us about ourselves.

“These are mortal remnants of an animal that lived 50 million years ago, and I’ve found bits and pieces that were left behind from that remote past. I think people have this innate question of ‘Who am I? Why am I here?’”

Beard, along with Luo, Wible, and Carnegie Museum anthropologist Sandra Olsen, is helping a new generation of students explore these very questions. In a course they designed called The Natural History of Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Medicine, they challenge medical students to consider how our own evolutionary history has made us prone to ailments ranging from chronic lower back pain to middle ear infections, and how basic evolutionary principles can factor into the treatment of patients today.

1. Chris Beard and his colleagues from France, Thailand, and Myanmar struggle to free their field vehicle from mud in rural Myanmar.

2. Paleontologist Dave Berman (center) and his colleagues consolidate a fossil vertebrate in a plaster jacket at the Permian Bromacker Quarry site in eastern Germany.

3.Invertebrate Paleontology Collection Manager Albert Kollar (left) and his colleague David Brezinski search for fossil reefs of Mississippian age in the Bridger Range in central Montana.

Strap On A Backpack—And A Live Ram

Olsen is another Carnegie scientist looking at a landmark development of our species; but she does it through the study of one of the human race’s allies in development—the horse.Olsen has spent the past decade excavating a remote site in northern Kazakhstan to learn more about the early domestication of the horse. During one field season, she says her team was so far from the nearest town that they brought a live ram with them that they had to slaughter in order to keep from running out of food.

Along with fellow researchers, Olsen found what may be the earliest known horse corral, at the site of a 5,600-year-old village in Kazakhstan. Chemical analysis of the soil revealed very high levels of phosphates, possible evidence of horse manure.

Olsen says she wants to know more about how the horse impacted human development. “It was the first form of rapid transit. It sped up migration, the development of trade networks, and warfare. With the domestication of horses, you see the spread of metallurgy, and the spread of languages and religious practices.” Her research is highlighted in the American Museum of Natural History’s upcoming exhibition The Horse.

Matt Lamanna, whose research has taken him to the Chinese Gobi, the Australian Outback, the Egyptian Sahara, and Argentine Patagonia, also is no stranger to remote places. “It’s like Wyoming meets the Nova Scotia coastline,” Lamanna says of Patagonia, where he’s now looking for fossils of dinosaurs from the Cretaceous Period, 66 to 146 million years ago.

Lamanna is carrying on a long tradition of dinosaur hunting at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and his study of the little-known dinosaurs of the Southern Hemisphere has taken him to Africa, South America, and Australia. In 2000, he was part of a team in Egypt that unearthed one of the largest dinosaurs ever found.

“Dinosaur exploration in the Southern Hemisphere is just beginning,” Lamanna notes with excitement. “Northern Hemisphere dinosaurs are relatively well known, but in the Southern Hemisphere, we’re finding lots of new species and even whole groups of dinosaurs that had been unknown before.”

The leading scientist behind the museum’s new blockbuster dinosaur exhibit, Dinosaurs in Their Time, Lamanna understands well how in-house research helps museums produce better learning opportunities for the public.

“I think any exhibit should be an accurate reflection of the most up-to-date science being done at that time,” Lamanna says. “Our research helps inform how we put the exhibits together.” In fact, the second and final phase of Dinosaurs, to open this June, will feature a new species of 66-million-year-old, bird-like oviraptorosaur that Lamanna and colleagues are currently studying. Another forthcoming section of the exhibit will highlight recent discoveries made by the museum’s paleontological staff on a rotating basis.

4. Botanist Cynthia Morton runs out recently collected DNA samples on a gel inside the museum’s Fisher Molecular Lab.

5. Local women teach anthropologist Sandra Olsen to spin wool at Lake Hovsgol, Mongolia.

6. Anthropologist Dave Watters excavates at the Trants site on the island of Montserrat in 1990.

7. Marc Wilson and fellow geologist Ross Lillie at the portal to the Herja mine of Baia Mare in the historic Maramures District of northern Romania. Photograph by Jeff Scovil

Connecting the Dots

Connecting the family tree of the 250,000 species of flowering plants is one of botany’s great mysteries. When did they develop? Which were the first species? Botanists don’t all agree on the answers. To help solve this puzzle, Cynthia Morton, Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s associate curator of botany, has been around the world tracking down obscure relatives of the citrus family to learn how these plants evolved.To collect her specimens, in 2003 Morton went to one stretch of western Australia so remote that one local guide confirmed, simply, that “no one has ever been here before.”

But lately, the lion’s share of her work has been keeping her right here in Pittsburgh, where Morton has been using her specimens to discover a new nuclear gene for all flowering plants. Only one other nuclear gene has ever been used for all flowering plants and it was completed more than 11 years ago. “We’re trying to understand the family tree of all flowering plants,” she says. “This kind of information can be very important in all kinds of fields—medicine, ecology, agriculture.”

Morton’s research has also supported the local Pittsburgh community. In partnership with Phil Gruszka of the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy, Morton compared the DNA of the London Plane Trees of Schenley Park in Oakland with nursery trees. The pair discovered that the nursery trees had little genetic diversity due to recent cloning practices in the industry. Because of this research, genetic material from Schenley Park trees has been given to nurseries to provide more diverse stock for resale.

|

Associate curators of invertebrate zoology John Rawlins (left) and Chen Young (right), on the top of Sierra de Neiba in a strange mountain meadow called Sabana del Silencio |

Among Rawlins’ newest discoveries is the “Finding Nemo moth,” so nicknamed because its distinctive orange-and-white striping closely resembles that of Disney’s fictional clownfish. Rawlins is worried that the moth’s habitat will soon be gone: It’s only been found in a small section of cloud forest in the Dominican Republic.

Saving the biodiversity of the planet is the ultimate goal of the project, says Rawlins. “We can’t protect everything. We have to prioritize what to protect, and those decisions have to be science-based. Humans are cooking the planet, and every habitat is being disturbed.”

Further south in the Caribbean, on the island of Montserrat, is where Carnegie Museum of Natural History curator and head of anthropology David Watters has been studying the earliest humans to settle the island. Pottery found by Watters in 1979 offered convincing evidence that those early residents came from what is now Venezuela around 500 BC. But, unfortunately for Watters, a volcano erupted on Montserrat in the mid-’90s, and many of his dig sites are now buried in up to 70 feet of volcanic sediment.

Not to be deterred, Watters is now working with a vulcanologist to identify the exact coordinates of the island’s most important archaeological sites for future study. “I probably won’t be able to work on these sites,” says Watters, “but as long as we locate where the sites were, they can be re-excavated in the future.

“For now, the artifacts we collected and photographs and field notes we made at these sites are all the documentation of these now-buried sites we are likely to have for many years. Re-locating these sites, in the now dramatically changed landscape of Montserrat, depends on accurate records made today. Our efforts will benefit Montserratians in understanding their cultural heritage and archaeologists in conducting future field research."

Underground is where you’ll often find Marc Wilson, collections manager and head of the section of minerals at the museum. In fact, visitors can view a video of Wilson underground as they enter the newly renovated and expanded Hillman Hall of Minerals and Gems. Wilson’s globe-trotting research in mines and mineral collections around the world has helped add to the museum’s impressive array of rocks, minerals, and gems.

After the fall of communism in Romania in 1989, the museum began to acquire important mineral specimens from the historic Maramures mining district in the northern part of the country. The area has been famed for its mineral wealth since antiquity, when the Romans mined gold out of the region. Wilson traveled to Romania in 2001 and was among the first westerners to view the mineral treasures of the Baia Mare Mineral Museum. His trip helped him procure top-level mineral specimens, like a ghostly, half-black, half-white, and triple-ball calcite specimen, and an ornate rose-colored rhodochrosite specimen. As a result, what may be the best collection of Romanian specimens in the United States can now be seen in Hillman Hall.

Wilson says he fell in love with minerals when he went to his first mineral show as a boy. His work at the museum is his way of sharing his fascination with the Earth’s natural treasures with others.

“That’s why I do this job,” he says. “I want the exhibit to spark the imagination for the handful of kids that are going to grow up and be the scientists of the future.”

Honoring a Daring Duo

Mary Dawson knows a thing or two about being daring. As a budding paleontologist, she was the only woman in her class at both Michigan State and the University of Kansas. She still laughs today, recalling that the same Carnegie Museum of Natural History director who told her a woman would never join the curatorial ranks named her full curator and head of her section eight years later, without a word of his short-sightedness.Above, Chris Beard and Mary Dawson in the museum’s Little Bone Room, showing off Mary’s latest discovery from the Canadian Arctic—a small, swimming carnivore. Photo: Mindy Mcnaugher

Today, at a spry 76, Dawson is technically retired, but you’d never know it. A slight, unassuming woman with an infectious smile, she still heads to the office every day, and remains an active field researcher, with plans to return to Devon Island in the Canadian Arctic. It was there, 30 years ago, that she unearthed prehistoric rhinoceros bones. Then, last summer, she and Canadian colleagues discovered the fossils of a small, swimming carnivore “no one had ever dreamed of.” She plans to go back again to learn even more—a trademark that has earned her the reputation, internationally, as one of the great paleontologists of her time.

It’s fitting that Carnegie Museum of Natural History has named its first-ever endowed curatorial position in her honor: The Mary R. Dawson Chair of Vertebrate Paleontology. Chris Beard, Dawson’s longtime colleague and current curator and head of the section has been appointed to the position, which is being funded through $2 million in private donations. This kind of endowed position is particularly significant in paleontology, says the duo, because by the field’s very nature, it takes time to bear fruit.

“This gives us the permanence of a position, so that the recipient can think long-term in his or her ideas, and be more daring in the kinds of projects they’re willing to undertake,” says Dawson.

“Through Mary’s leadership over decades, this museum built what is at least, ounce per ounce or per capita, the best paleontology group in the world,” adds Beard. “It’s not easy to build a group like that, and it might be even harder to keep a group like that together. Stability, long-term, is important.”

Beard and Dawson have been friends and close collaborators since 1989, when Beard joined the museum as a curator. The pair studies different animals that once lived together, so they often compare and contrast their findings. In 1995, during one of the duo’s joint field expeditions to China, they were part of a team that discovered Eosimias, a 45-million-year-old fossil primate from China now recognized as being the oldest and most primitive known relative of monkeys, apes, and humans. They were hailed by the paleontology community as finding humankind’s “Garden of Eden.”

“Both Chris and I are very dedicated to the concept of paleontologists being field people,” notes Dawson. “Discovering new things—and then, when you can, following through and studying them. What happens, though, is that you collect more than you can study. So, by building the museum’s collection, we’re building up not only for our own research, but for research projects in the future.”

Traveling Warhol · The Art of Being Human · Seeing Stars · The Future is Now · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Face Time: Matt Wrbican · Science & Nature: A Scoop Full · Artistic License: Animal Attraction · First Person: Full Body Experience · Then & Now: The museum as classroom

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |