Spring 2008

Spring 2008

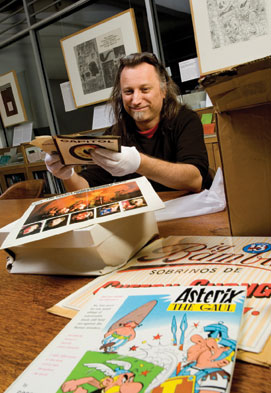

Photo: Tom Altany |

For going on 17 years, Matt Wrbican, The Warhol’s archivist, has literally been unpacking Andy Warhol. One hundred and sixty boxes down, 500 to go—with no fewer than an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 objects inside those famed Andy Warhol Time Capsules. But this year, thanks to the support of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Wrbican is getting some much-needed help popping the tops off of Andy’s remaining cardboard boxes, which are filled with the mundane and the extraordinary items of his daily life—clues to the man behind the icon. The timing couldn’t be better, explains Wrbican, pegged by colleagues as having encyclopedic knowledge of the revolutionary artist and who, in a given year, responds to hundreds of requests for information about Warhol and objects from the museum’s massive archives. After all, Warhol’s hotter than ever, he says. “Sometimes I wonder when the interest is going to wane. But it doesn’t seem like it’s ever going to at this rate.” For going on 17 years, Matt Wrbican, The Warhol’s archivist, has literally been unpacking Andy Warhol. One hundred and sixty boxes down, 500 to go—with no fewer than an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 objects inside those famed Andy Warhol Time Capsules. But this year, thanks to the support of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Wrbican is getting some much-needed help popping the tops off of Andy’s remaining cardboard boxes, which are filled with the mundane and the extraordinary items of his daily life—clues to the man behind the icon. The timing couldn’t be better, explains Wrbican, pegged by colleagues as having encyclopedic knowledge of the revolutionary artist and who, in a given year, responds to hundreds of requests for information about Warhol and objects from the museum’s massive archives. After all, Warhol’s hotter than ever, he says. “Sometimes I wonder when the interest is going to wane. But it doesn’t seem like it’s ever going to at this rate.” It had to be exciting joining the museum in its infancy, even before it opened its doors. What was your role? I think I was something like the fifth person hired. I moved to New York City and worked in Warhol’s studio where all his art supplies and the rest of his stuff were located. A lot of what I did at that time was just count things, making endless lists for two years. I inventoried box after box, and as far as Warhol’s Time Capsules go, we inventoried them every Friday, all day long. I also acted as a courier on a lot of the trips to Pittsburgh. In all, it took about eight truckloads of stuff to get everything to the museum. What’s your background? For an archivist, my background is really unusual in terms of degrees. I didn’t study library science. At Carnegie Mellon I processed a collection for the university archives, so I had the experience. My degrees are in fine arts, and I think that combination helped me get the job. When I was hired, I was just finishing a job at Carnegie Museum of Art as assistant to the exhibition coordinator for the Carnegie International. Had you studied Warhol? I knew his work generally; I wasn’t any kind of an expert. Was it intimidating not knowing much about him? Now I know too much, maybe. But from the beginning, it was about the fun of learning. There were already a couple of biographies that had been published about him about two years before I was hired. So I read those. That’s pretty much the same training I give my interns now. Reading those biographies, that’s their initiation in a way. Your responsibility is much broader than many people would assume. What’s your role today? I’m responsible for all the archival exhibitions, not just in the Archives Study Center but what you see all over the museum. Like with the recent Keith Haring show, Tom (Director Tom Sokolowski) asked what we have relating to Warhol and religion. I have a good knowledge of what’s in the collection, and I do a lot of digging. I curated 6 BILLION PERPS, I was part of the team for Body/Booty, and I did the few archival bits that were in Andy and Oz. I worked with Glenn Ligon for four days while he was here preparing for his exhibition last year. Another part of your job is being a resource for researchers. What kinds of people come to you for help? Curators, PhDs, graduate students, filmmakers, writers. We worked with Ric Burns when he made the documentary about Warhol for PBS. We’ve worked with TV producers from England, France, Japan, Germany, I forget where all. Right now publishers from London are coming to do photo research. Has any of this outside research ever led you to a new piece of information? Usually they inquire about things we’ve encountered before. But about 15 years ago, a guy called and told me that his parents were students at Carnegie Tech in the ’40s. They had drawings that were done at the school’s spring carnival by a guy named Andy. It turned out they were Warhol’s drawings. Apparently Warhol set up a little booth where he would draw your portrait for 50 cents or a dollar, and this couple has pencil portraits of themselves drawn by Warhol. They’re pretty nice portraits, and it’s a really, really great piece of information about Warhol that we never knew. The tragedy is that they had the drawings dry mounted onto Fome-Cor, which is, as far as I know, irreversible. It sounds like part of your job is playing detective? It’s a little bit like archeology, and the Time Capsules in a way really are like that. Every time we open one, we learn a little something new. It’s not always earth-shaking, but sometimes there’s a nice new piece of the puzzle that’s revealed, and there are still a lot of unanswered questions with Warhol. Hopefully, by the end of the Time Capsules project, we’ll have a lot of them answered. What’s the plan and timeframe to get the rest opened? The grant we received from The Andy Warhol Foundation is for a six-year period, and that was requested based on previous experience. But we’ll see how it goes. We’ve just hired three full-time project cataloguers. Why is this work a priority? When we presented to the Foundation board, it wasn’t so much what we said as what we brought with us. We brought 15 to 20 examples from the Time Capsules that have not yet been catalogued. They were things like a great telegram from Diana Vreeland (curator of the Met’s Fashion Institute), a couple works of art by Warhol, and publicity materials for an exhibition that Warhol had in Kuwait that nobody really knows much about. That’s where his Dogs & Cats paintings were shown. You travel with the Time Capsules when they’re part of a traveling show. Where have you been recently? I just returned from Brisbane, Amsterdam, and Stockholm. I gave a talk in Edinburgh when they borrowed two Time Capsules for a show last summer. If a museum borrows a whole Time Capsule or more, then it requires a courier because all those objects need to be condition checked and installed in a way that is safe for the objects. It seems like we get more and more requests, so I’m traveling more than I did. What’s the attraction to the Time Capsules, specifically? The Time Capsules are completely different than his visual art because they’re autobiographical. They tell you about Warhol’s life: who he was, what he was doing, where he was going, the people that he knew. Because of them, we know a lot more about his life than we would otherwise. Since Warhol didn’t really write a lot down, there’s a lot of stuff that we don’t know about him. Even his published diaries only cover the last 10 years of his life, and he was 58 when he died. We’ve found about 20 pages of Warhol’s diaries that predate the published version by about four years. Do you get Warhol-ed out? There are a lot of different facets to Warhol. There are so many ways to look at him. I don’t think there are many artists in Warhol’s generation you could do a wiretapping show around. We’re doing a dogs and cats show now (curated by Wrbican). This summer we’re doing a small show about Warhol’s cookbook, Wild Raspberries. The amazing thing about Warhol’s archives is that you can look at almost any topic and do an exhibition. |

Also in this issue:

Traveling Warhol · The Art of Being Human · The Explorers Club · Seeing Stars · The Future is Now · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Science & Nature: A Scoop Full · Artistic License: Animal Attraction · First Person: Full Body Experience · Then & Now: The museum as classroom

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |