|

|||||||||

|

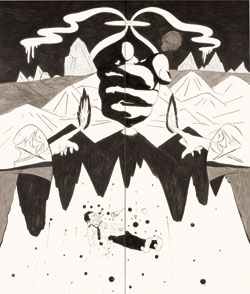

Above, a detail of an installation view of Korean artist Haegue Yang’s Sadong 30 (2006), an example of “the poetic nature of everyday life,” says Douglas Fogle, curator of the 2008 Carnegie International.

|

THE ART OF BEING HUMAN

Even on the fast train from Seoul, it took over an hour to get to Incheon. The two cities are close enough to be considered part of the same South Korean megalopolis, their combined populations approaching 13 million people. That’s the kind of figure that makes even New Yorkers nervous, yet the industrial zone of Sa-dong in Incheon, to which Douglas Fogle traveled last fall, was empty enough to seem “the middle of nowhere,” in his mind. Once in Sa-dong, Fogle, Carnegie Museum of Art’s curator of the 2008 Carnegie International, sought out the abandoned house he’d been directed to. “It was a little house in a back alley that was falling apart, decrepit,” says Fogle. But inside was something remarkable. Colorful paper, hand-folded into iconic origami—stars, anemones, geodesic shapes—was illuminated by low-hanging naked bulbs and strung lights. Piles of detritus were lighted with similar affection, as were the house’s ramshackle fittings and peeling wallpaper. This was Sadong 30, an installation piece by Korean artist Haegue Yang, made in—and, indeed, from—a house once belonging to her grandmother. “It was so poetic, so incredible,” says Fogle. “The trip on the train was part of it, meeting and talking with her was part of it; she’s very philosophical, very poetic in the way she talks about things. It was very comparable to the kinds of ideas I was thinking about for the International, this idea of intimacy, and the poetic nature of everyday life. It was a very formative moment for me in this exhibition.” Those ideas eventually solidified into Life On Mars, the 55th Carnegie International, a show that stems directly from Fogle’s ‘boots on the ground’ curatorial approach. Over a heavy, two-year travel schedule, where he racked up some 200,000 miles by air, Fogle viewed the work of artists from Mexico City to Singapore, São Paolo to Berlin, the back alleys of Incheon City to a Hollywood cutting room. In doing so, he’s assembled a show that is truly international, but without succumbing to the now-hackneyed themes of “the global.” A show that hopes to speak equally to the most well-versed of art critics and to contemporary art’s first-time visitors. “I guess ‘human’ is the word,” says Fogle. “These are very sophisticated artists, working in metropolitan centers, huge cities, yet there’s something incredibly human about their work.” In other words, while creating a show about life on Mars, Carnegie Museum of Art will tell a story about what it’s like to live right now, right here on Earth.

Learning a New LanguageThe Carnegie International was born at the end of the 19th century at the behest of Andrew Carnegie and as part of his vision of a museum explicitly of modern art.

“I look at it as R&D [research and development] for the culture industry,” says Fogle. “Even since the 1890s, this show has been about the new, and for me, this show is the past 20 years of art all mixed together. There's a balance, from the art professional’s point of view, between names they know and some that they don't know. There's a balance between the 29-year-old artist in their first major exhibition and a 90-year-old artist who’s painting every day, and whose work feels like a young artist.” Life On Mars will certainly appeal to arts professionals. But perhaps more importantly, it’s a show capable of drawing in the contemporary art newcomer, too. To some extent, that’s a product of Fogle’s personal background. Rather than an art-history-educated insider, Fogle came to curating as simply an art lover, beginning his curatorial career at Minneapolis’ lauded Walker Art Center in the early 1990s. Since arriving at Carnegie Museum of Art, his Forum shows have pointed in the general direction of Life on Mars, showing work by exciting, young, international, multi-disciplinary artists such as Britain’s Phil Collins—whose video art the world won’t listen has gone on to become one of the more talked-about pieces of contemporary art in current layperson’s pop culture. With a background and education from outside of the art world, having studied political philosophy and international relations, Fogle has an understanding of the difference between the language of art and the language of the general culture. “We grow up watching movies from the time we're three years old—there’s a grammar to film narrative that we all feel comfortable with, without even thinking about it,” says Fogle. “We don’t grow up knowing the language of contemporary art, and that's something that intimidates people, and it shouldn’t. But I understand that, because I had to learn that language, too.” The very title, Life On Mars, is a part of bridging that divide—not only is this the first International to bear a title, it’s one that poses many rhetorical questions that we grapple with today. What constitutes “home,” “family,” even “humanness” in this globalized, digital age? “I think it's really important to have a title for an exhibition, which makes it seem more approachable—one that asks a question, that makes people interested,” says Fogle. “What is the title about? What does it make you think of? Some people get the David Bowie reference to his 1971 song, ‘Life On Mars?;’ some people think of space exploration. The way I like to talk about it is it’s a poetic way of asking, ‘are we living on a strange world?’ The art world itself is Mars—the best contemporary art asks you more questions than you sometimes have answers for.” Back to the GritTo approach the themes of Life On Mars—of “what it means to be human” in today’s world—Fogle has chosen artists whose work shares a manual energy, whose media feels hand-hewn and bears the mark of skin and bone.

Haegue Yang understands Life On Mars to pose a question not just about where we live, but how we live. “Mars doesn’t sound so unfamiliar to me,” says Yang, in an interview filmed for the International’s web site, set to go live in March. “Not that I have any knowledge or understanding of Mars as a place to live in, but [in the way that] any place that sounds unfamiliar seems to me very familiar. I’m concerned with this constant question of how to live, and where to live.” Conspicuous in its absence from the 55th Carnegie International is the technological stamp of “new media” art born by computers or on the Internet. Rather than an end unto itself, the computer has returned in Life On Mars to its origins as a tool. Because while the show itself may concentrate on the grittier side of cosmopolitan artwork, the Carnegie International has taken its mission and its marketing digital—and global—in a way it never has before. Making A MarkWill Real doesn’t downplay the role of technology in a 21st-century museum exhibition. After all, as director of technology initiatives for Carnegie Museum of Art, it’s part of his job to initiate and implement new ideas for using the technology to advance the museum’s missions. But he’s no tech fundamentalist—Real is the first to point out that the Web has inherent limitations in the display of contemporary artwork, and for that reason, perhaps, he’s the perfect person to put Life On Mars online.

Where Carnegie Museum of Art sees new possibilities for technology and the International is not in its artwork or its display of work, but in the way the museum communicates with and involves its audience. To that end, for the first time, the International web site will include numerous opportunities for visitors to participate, by blogging, commenting, bookmarking, sending content to friends, and tagging. In this way it will have much in common with popular social-networking tools such as Myspace and Facebook, and interactive media outlets such as YouTube and Flickr, which will allow users to comment on videos and images related to the exhibition. The museum will encourage users of these other sites to post links to their content on the International web site, and will establish a Web presence beyond its own site by contributing its own media content for viewing and commenting by the wider world of Web users. “The idea that the museum is the only valid voice to be heard on the content of the International is one we’re trying to get away from,” says Real. “We want to provide a vehicle for people to express their own views, on the theme and on the artwork.” Made possible by a $150,000 grant from The Fine Foundation, the International will not only have an interactive presence on-line, but visitors will have an opportunity to access and contribute to those resources onsite, before, during, or after their visit to the show. It’s a concept that goes hand-in-hand with the show’s themes, notes Jordan Crosby, school and teacher programs specialist for the museum. Individuals submitting their voices to the vastness of the Internet is a lot like an artist trying to make a tiny mark on his or her vast, global culture. “The whole idea of people blogging, representing themselves in the ‘blogo-sphere,’ parallels nicely with this generation of artists working humbly and with these mean materials,” Whether it’s an internationally known artist creating an installation for the International or teenaged visitors sitting down to tap out their thoughts about it on a computer keyboard, Life On Mars comes back to that mark on the cave wall—the mark that makes us human.

“The basic elements of art-making are actually what make us human,” says Douglas Fogle. “Our ability to make a mark, whether it's a cave painting or a mark in the sand. Putting the pencil to paper, that connection between the graphite and the paper, this gesture of making a mark that has some intelligibility—in some ways, that is what it means to be human.”

|

||||||||

Traveling Warhol · The Explorers Club · Seeing Stars · The Future is Now · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Face Time: Matt Wrbican · Science & Nature: A Scoop Full · Artistic License: Animal Attraction · First Person: Full Body Experience · Then & Now: The museum as classroom

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |