He’s the vision of innocence, his tiny hands folded over a faded dressing gown, his cherubic face framed by a baby bonnet. At first glance, Johannes Orlovits might be mistaken for a sleeping infant. But upon closer inspection, there are eerie signs of an 18th-century death—desiccated skin, tiny brittle toes, hollowed out eye sockets. He’s a child mummy, and flanking his 1-year-old body are his mother and father, forming an otherworldly portrait of a Hungarian family frozen in time.

The Orlovits family is part of a group of 18th-century mummies uncovered just north of Budapest in two long-forgotten burial crypts.

The Orlovits family, discovered in their mummified state in a church crypt in 1994, is one of the most haunting and astonishing findings at Carnegie Science Center’s Mummies of the World: The Exhibition.

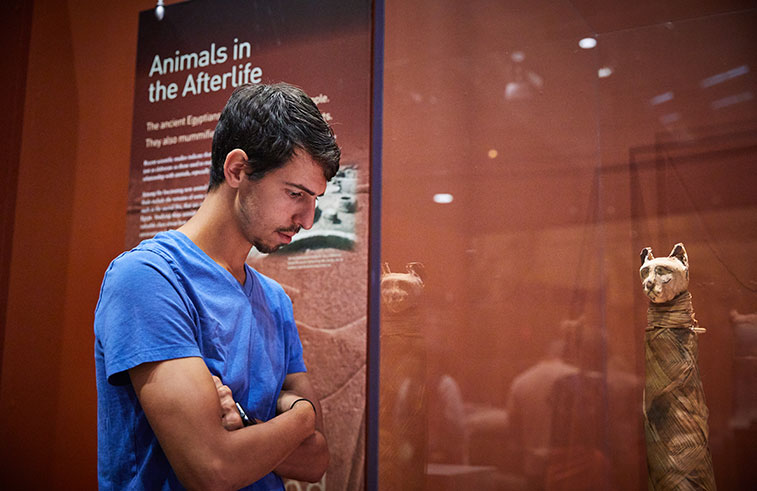

When most people think of mummies, they think of the ornate, wrapped bodies from ancient Egypt. This exhibition has Egyptian mummies intentionally preserved for more than 2000 years. But it also includes mummies formed unintentionally by a twist of the environment—bodies preserved in bogs, deserts, crypts, or ice. For this natural process to occur, circumstances must be just right—extreme cold, arid conditions, or lack of oxygen—to stop decomposition.

Mummies of the World challenges notions of what constitutes mummies and where they can be found. There are South American mummies, European mummies, mummies inside baskets, animal mummies, shrunken heads, a stolen mummy that was sold on eBay, bog bones, even a modern-day North American mummy created in a university basement.

Robert Brier, the Long Island University Egyptologist who co-created the modern mummy, says the exhibition fascinates people of all ages. “It’s a terrific show. A kid will stare at a mummy as long as you let them,” he says. “It’s a taboo. Kids don’t get to talk about death and this lets them do it. Adults are fascinated with immortality because a mummy is recognizable. It’s almost like they cheated death, and in a way, we are envious.”

Real people, real stories

The fascination with mummies, found both in museums and cheesy horror films, has deep roots. Two hundred years ago, British doctors sent invitations and even sold tickets to prestigious events where Egyptian mummies were unwrapped, says Margaret A. Judd, associate professor of anthropology at the University of Pittsburgh. After the unwrapping party, “the mummies would be destroyed or perhaps lay forgotten in the doctor’s attic. Thankfully times have changed and we are more respectful of the past.”

In Mummies of the World, experts piece together the unique stories of 40 ancient people and animals through old records and modern technology, often challenging long-held notions of death.

A close-up of Michael Orlovits’ mummified hands, with a cross left intact.

Baby Johannes and his parents may have been lost to history had it not been for repair work on the Dominican Church of Vác in Hungary. When a crack was found in the church’s wall, a bricklayer pounded through, unearthing a hidden staircase that led to a crypt. Inside were 265 coffins, stacked from floor to ceiling. While those near the bottom contained only bones, the coffins at the top of the pile were preserved as mummies due to the cool, dry air circulating through the underground chamber. Everything, from their rosaries and the handmade stockings on their feet, was left intact. Scientists speculate that the oil in the pinewood coffins may have prevented the growth of fungi and bacteria, which cause decomposition.

Modern testing showed that Veronica, the 38-year-old mother of Johannes and two other children who died before the age of 2, suffered from tuberculosis. The highly contagious bacteria was a common killer in the Orlovitses’ Hungarian town on the Danube River in the 18th century.

“Veronica looks very peaceful here, but the scan shows that her legs were so thin she wouldn’t have been able to walk later in life,” says Kathy Leacock, director of collections at the Buffalo Museum of Science, which loaned mummies and artifacts to the exhibition. Johannes likely did not die of tuberculosis because his face is chubby, she says.

Scientists can perform noninvasive testing of mummies to piece together the narrative of how people like the Orlovits family lived. And CT scans can be rendered into a 3D image of a mummy. “This allows us to peel back the external wrapping and even the tissue to expose the skeleton that lies underneath,” says professor Judd of Pitt. “Those bare bones allow us to estimate the individual’s sex and age, and provide evidence of injuries, joint disease, and dental disease.” Bone and dental samples can offer clues on where someone was raised as a child and what they ate as an adult.

In addition to modern technology, dusty church records contained a wealth of historical information about those found in the crypt. Veronica’s husband, Michael Orlovits, was a miller who died at age 41. The three family members are dressed in recreations of their burial outfits.

“A kid will stare at a mummy as long as you let them. It’s a taboo. Kids don’t get to talk about death and this lets them do it.”

– Robert Brier, Long Island University Egyptologist

Baron von Holz, a 17th-century nobleman mummified naturally due to the environmental conditions of the family crypt, found still wearing his leather boots.

In another room of the exhibition, the mummy of Baron von Holz lies in a display case, wearing luxurious, knee-high brown boots—the only remnant of the sartorial splendor of the 17th-century German aristocrat. The soles of the boots are pristine. “You can see that they were never used in life, and they were procured for his final resting place,” Leacock says. “Researchers speculate that they might have had buckles on them at one time.”

History tells us that baron and his relatives hid inside Sommersdorf Castle in southern Germany during the bloodshed of the Thirty Years’ War. They were later buried in the family crypt at Sommersdorf, until Napoleon’s forces took over the castle and found them in a mummified state. The vault was opened and resealed several times before descendants of the family recently gave permission for five of the mummies to be studied and exhibited.

The usefulness of death

Kids who stare in wonder at mummies often ask if they can touch. The answer is a definitive no. But Mummies of the World provides visitors with the next best thing: a touch display that provides a realistic representation of what mummy parts actually feel like. For example, mummy skin feels like sandpaper, while the bones are very squishy and pliable.

The show also features mummy bundles—bodies that were curled up in the fetal position, wrapped in long grass or reeds, and preserved inside baskets or textiles. The basket mummies on display are most likely from the highlands of Cuzco, Peru. Leacock notes that the people who prepared mummy bundles occasionally put a fake head on top because the real heads were sometimes looted—part of the sordid history of mummy abuses and body-part sales. Other mummy bundles are wrapped in textiles, such as the young South American girl on display, the linen visible beneath her mummified body.

A mummy bundle preserved inside a basket.

Another display case holds shrunken heads, the result of a gruesome ancient ritual performed by the Jívaro Indians of northern Peru and southern Ecuador. Tribe members would kill their enemies, shrink their heads, and wear them around their necks as trophies. In addition to human heads, the exhibition shows a shrunken sloth head that apprentices practiced on before advancing to human heads.

A war trophy known as a shrunken head.

While mummies have been abused and sold on the black market throughout history, they’ve also been preserved for medical training. Mummies of the World contains some of the famous Burns Collection, medical mummy parts from early 19th-century Scotland.

While he didn’t record his methods, in the early 1800s physician Allen Burns of Glasgow’s College Street Medical School devised new methods of preserving human specimens. Researchers believe he used an embalming solution containing arsenic, mercury, nitrates, oxides, and other chemicals.

A medical mummy from the 19th-century Burns Collection.

When Burns died in 1813 at age 32, his first assistant, Granville Pattison, bought the collection and eventually migrated to the United States. He later sold the collection to the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Most of the 100 anatomical specimens remained safe and secure at the university, but a few disappeared mysteriously. On October 10, 2006, a mummy of a child from the Burns Collection was listed on eBay under the category of “medical specimen,” and bidding reached $500. The item was pulled from the site after police arrested a woman from Port Huron, Michigan, for trying to sell it.

Despite its journey into the black market and the less-than-ideal storage conditions of a police station, that child mummy remains in pristine condition, proving Burns clearly knew how to preserve his specimens.

“To see a dead body that looks almost perfect, it throws us for a loop. As long as the conditions are right, it can happen anywhere.”

– Cassandra L. Kuba, professor of anthropology at California University of Pennsylvania

A modern-day mummy created by scientists in 1994 using the same methods as ancient Egyptians.

So does Bob Brier, known as “Mister Mummy” because he co-created the first modern-day ancient mummy using secrets left behind by the Egyptians. “I was reading things on Egyptology, and most of the people writing about it didn’t know what they were talking about,” he says. “There were loads of things we didn’t know about the mummification process. The only way to find out was to do it.”

In 1994, he collaborated with anatomist Ronald Wade of the University of Maryland School of Medicine (home to the Burns Collection) to preserve a male body that was donated to science. Brier traveled to Egypt and dug up 400 pounds of natron, a drying agent similar to salt and baking soda, on the shore of the Nile. He also bought frankincense, myrrh, and other spices from the local market, as well as obsidian blades and other tools.

Back at the University of Maryland, the two researchers replicated the conditions of an ancient Egyptian ibu tent, purifying the walls with palm wine and water before covering the body with natron.

Brier debunked the common theory that the ancient Egyptians pulled the brain out through the nasal cavity, chunk by chunk. Instead, he says, they liquified the brain by twirling a wire hook like a whisk and then turning the body on its side and letting it flow out. Using an obsidian blade as their scalpel, they then cut a 4-inch incision through the abdomen and removed the liver and other organs. The pair also put frankincense and other spices in the cavity to neutralize the odor.

For the next 70 days, they left the body alone. In the end, they discovered the process worked and wrapped it in linen. Twenty-five years later, the modern mummy, dubbed MUMAB for Mummy of the University of Maryland at Baltimore, has not decomposed.

“I felt a real kinship with the ancient embalmers,” says Brier.

An Egyptian cat mummy dating to the early Roman period, when felines were ritually embalmed in a lengthy process using salt and various resins.

Other modern mummies can be found locally, says Cassandra L. Kuba, professor of anthropology at California University of Pennsylvania. At the request of Carnegie Science Center, she and five of her undergraduate students brought some naturally mummified animals to show visitors. Among the local finds are a chicken found behind farm equipment and a toad found on railroad tracks.

“To see a dead body that looks almost perfect, it throws us for a loop,” says Kuba. “As long as the conditions are right, it can happen anywhere.”

Mummies of the World at Carnegie Science Center is presented by Agora Cyber Charter School and sponsored by Baierl Subaru.

Ancient Egyptians: A lust for life, even after death

More than 2,000 years after his death, Nes-Hor retains the regal air of someone who tended to the gods. He once worked inside the Temple of Min in ancient Egypt, helping to clothe, clean, and make offerings to the statues of the deities. Now the mummified body of the ancient priest is on display in Mummies of the World: The Exhibition at Carnegie Science Center.

Adjacent to him is the mummy of Nes-Min, another priest in the Temple of Min from the Ptolemaic period, dating from 305 to 30 BCE. The pair not only bathed the gods but likely themselves, sometimes three or four times a day, all in hopes of purifying their spirits for the afterlife.

Because the exhibition, on view through April 19, 2020, has a world of mummies to showcase, Egyptian mummies and artifacts are kept to one room. But those who want a more in-depth look at both the mystery and vibrancy of everyday life in ancient Egypt society can head to the Walton Hall of Ancient Egypt at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

This longtime visitor favorite includes a rich collection of mummies and hundreds of artifacts dating to 3100 BCE. Its centerpiece, a reconstructed tomb, contains the mummy and coffin of an Egyptian chantress of Amun, dating to 1069 BCE. Despite Andrew Carnegie’s fascination with dinosaurs, in 1896 the temple singer from Dynasty 21 was actually the first scientific artifact he purchased.

The hall also showcases the lesser known but no less fascinating coffin of Heramenpenaf, a wab priest at the temple of the deified Amenhotep I, who was believed to be supervising the construction of the tomb of Ramesses XI.

“He was a middle-of-the-road priest, not at the bottom, not at the top. He would do general rituals at the temple,” such as cleaning, cooking, taking care of livestock, and preparing for festivals, says Erin Peters, an Egyptologist and research associate at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. The outside of the coffin is damaged by marks believed to be made by an ax. Some of the gold is missing from the outside, leading to speculation that thieves looted it.

In ancient Egypt, priests served a different role than the religious leaders of today, Peters explains. They didn’t interact with worshippers or preach during services but tended to the temple and statues of the gods. “There were many priests in each temple, and they kept building more and more temples,” she says. “Priests had many different roles. Some were butchers. Some were doctors. Others took care of the cult statues, feeding them and taking the clothes of the deities off and putting them back on.”

Then there were the funereal priests who presided over the mummification and burial of the dead, an important ritual for the Egyptians. After death, most of the organs were removed and the bodies were covered in natron, a natural drying agent made of salt and sodium bicarbonate, and then wrapped in linen. The wealthy were buried with handcrafted masks in elaborate coffins, painted with ornate scenes and inscriptions. The scenes, displayed on coffins and coffin fragments, were supposed to protect the ancient Egyptians and guarantee their immortality.

“People think of Egyptians as fascinated by death because of the amount of time and energy they spent on it,” Peters says. “But really they were obsessed with life. They saw it as continuing life on Earth, but just a little better. They thought you had to have a body to get to the afterlife.”