One spring day in 2018, art curator Rebecca Matalon found herself in a Chelsea carriage house that had seen better days, trying to discern if the objects around her were sculptures or just useable chairs and tables. Lurking in the shadows were wonderfully strange riffs on iconic modernist designs encased in cheap foam and dripping with putty.

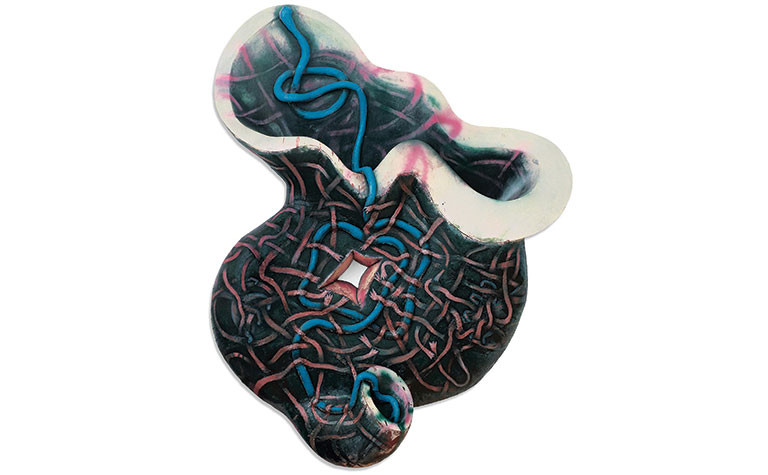

“It was invigorating,” Matalon recalls of her visit to artist Jessi Reaves’ former New York studio. “Reaves juxtaposes material to disorient the distinction between high and low, and merges ornate—even baroque—decorative flourish with almost foul bodily forms and materials.”

While Matalon was absorbed by what she calls the “perversity” of Reaves’ blending of the functional and the sculptural, there was something else that drew her to the work. “I had an ‘aha’ moment,” says Matalon. “I finally understood [artist] Elizabeth Murray through Reaves.”

Jessi Reaves, Twice Is Not Enough (Red to Green Chair), 2016, Collection Hope Atherton and Gavin Brown, New York, New York

That experience inspired Wild Life: Elizabeth Murray & Jessi Reaves, on view in Carnegie Museum of Art’s Heinz Galleries through Jan. 9, 2022, following its debut at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, where it was organized by Matalon. At once a survey of both artists and a dialogue between their work, Wild Life is also an opportunity for Pittsburgh museumgoers to explore more fully the genre-bending creations of two Carnegie International alumni (1988 and 2018, respectively), each with multiple works in Carnegie Museum of Art’s permanent collection. Visitors to the most recent International may remember lounging on a sprawling web of ottomans made by Reaves that looked a bit like poured metal and was displayed in the museum’s Heinz Architectural Center. Murray’s Don’t Be Cruel, made in 1986 and featuring a cracked table twisting apart in space, usually consumes nearly an entire wall in the museum’s Scaife Galleries.

“I think it’s significant for our public that we use the museum’s exhibition program to check back in with artists who were featured in past Internationals,” says Eric Crosby, the Henry J. Heinz II Director of Carnegie Museum of Art. “An International provides a snapshot in time, but an exhibition like this allows us all to experience the work in greater depth.”

“The way that Reaves’ work makes disintegration seem pleasurable brought me back to Murray. I was able to name how both artists were binding pleasure and repulsion to the home and body, rendering both on the very brink of collapse.”

– Curator Rebecca Matalon

At first, the connection Matalon makes between Reaves and Murray might seem odd. Born 46 years before Reaves, Murray worked using a different medium, painting.

“The way that Reaves’ work makes disintegration seem pleasurable brought me back to Murray,” Matalon explains, admitting that she previously struggled to fully appreciate Murray, who in 2005 became the fifth woman ever to be celebrated with a retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. “I was able to name how both artists were binding pleasure and repulsion to the home and body, rendering both on the very brink of collapse.”

Jessi Reaves, Emotional strategy sconce, 2020, Collection Carolyn Ramo. Image courtesy the artist.

Ambiguity and contradiction

Reaves first explored remixing classic modernist furniture—refusing the distinction among art, craft, and design—while doing mostly upholstery work in a furniture-design studio after graduating from the Rhode Island School of Design. She received her BFA in 2009, during one of the worst economic downturns since World War II. At the studio, she was able to use the owner’s tools and discards, making assemblages from found material as many artists living through recessions did before her.

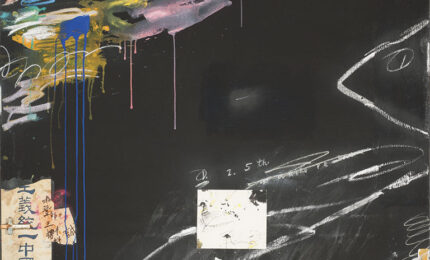

Elizabeth Murray, Tangled, 1989-90, Collection Dr. Robert Feldman, Cohoes, New York, ©2020 The Murray-Holman Family Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Like Reaves, Murray is difficult to categorize, which partially explains why she hasn’t been adequately celebrated since her untimely death in 2007. Working during the 1970s–90s, Murray was a contemporary of artists such as Jack Whitten, Alan Shields, Lynda Benglis, and Richard Tuttle, and came of age as an artist responding to minimalism, pop, and surrealism. She remained resolutely committed to painting even as critics debated its relevance, and as conceptual and performance art were becoming an ever-increasing part of the discourse. Her work is often a discomforting mingling of abstraction and representation, breathing fresh life into domestic objects such as cups, utensils, and tables—and painting itself. In her images, the references are often intentionally multiple. In Fire Cup, for instance, the image is both Murray’s signature chalice tipped on its side as well as sperm penetrating a cream-colored egg, says Matalon. “This ambiguity, this multiplicity is also key,” she says. Bordering on the sculptural, Murray’s monumental, cartoon-like inventions burst through the confines of the traditional canvas. Making It Up, made in 1986, takes up 80 square feet and has twisted corners, resembling a sheet snapping in the wind. The similarly sized Heart and Mind, created five years earlier, consists of two pieces—one curved like the body of an ant, the other angular and painted with oblong ovals that, taken together, create a dizzying optical illusion.

Additional commonalities between the artists emerged as Wild Life took shape, says Matalon, noting that Reaves relished the opportunity to have her work in conversation with Murray’s. In an interview for the exhibition’s catalogue, Reaves says she’s long admired how Murray’s paintings have an aggression to them. She recalled seeing Murray’s work for the first time in Chicago, as she was moving to New York. “Some of [the paintings] seemed to peel off the wall like roadkill. I felt they were really arrogant in terms of how they took up space—not just wall space but how they jut out into the room,” she says. “Following that, I’ve collected books of her work. Periodically looking at them has certainly influenced my own work.”

Elizabeth Murray, C Painting, 1980-81, Collection Eleanor and Bobby Cayre, New York, New York, ©2020 The Murray-Holman Family Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Both artists are interested in ambiguity and contradiction, notes Matalon, adding that she sees ambiguity as part of a feminist approach, which resonates with her ethos as a curator, and is also rooted in feminism. “I’m interested in artists who are historically marginalized—women, artists of color, artists working in a way that makes them difficult to place,” she says. “My work comes from a feminist conception of what it means to make an exhibition in terms of a nonhierarchical presentation of objects and histories, one that values similarities and differences, but also one that is always deeply invested in the understanding that there is not a singular history of art.”

Matalon notes that, at a certain point in her career, Murray would have bristled at being linked to feminism. In 1984, Murray told Paul Gardner of ARTnews: “If some women choose to push feminist images or make quilt art, that’s fine, but I’m not interested in doing that. If the feminist emphasis seems too calculated, I find the art hard to take.” She feared her work would be dismissed if labeled “women’s art.” However, she learned that disavowing feminism didn’t prevent her from being passed over. By the mid-1990s, Murray was sick of the art world’s “old boys club.” She joined the Women’s Action Coalition, a group advancing women’s rights through direct action, and she began protesting the lack of diversity in museums. In 1995, she organized an exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art featuring more than 100 works by women. In her curator’s statement, she wrote, “I did not want the show to be political. … But I realized soon enough that it is political.”

“The narrative that Murray’s work is not feminist persists,” says Matalon. “But making maternal and domestic subject matter central to your work during that time meant you ran the risk of marginalization, and Murray did so from the beginning. That is, knowingly or not, very much a feminist gesture,” she continues. “Motherhood is still really taboo today, though that is changing, if incrementally.”

There are also feminist implications to Reaves’ work, as she intervenes in a narrative of masculine modernist masters with lyrical and playful flourishes, including the use of materials like gauze that are considered feminine. “The design world is undeniably, throughout history, a male-dominated field,” Reaves told Josephine Graf of Mousse Magazine. “I’m dealing with a masculine/feminine binary.” However, as Wild Life makes clear, Reaves and Murray exist in very different historical contexts, and the meanings and implications of feminism have shifted and changed over time.

Elizabeth Murray, Night Empire, 1967-68, Collection Arthur and Susan Murray Resnick, ©2020 The Murray-Holman Family Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In part, it was Matalon’s ambition to pair these seemingly disparate artists without erasing their differences that prompted Crosby to bring Wild Life to Pittsburgh. “We wanted to present this show because of the clarity of Matalon’s curatorial vision,” he says. “It’s the curator’s role to discover and ultimately invite the visitor into the many wonderful correspondences and echoes, similarities and differences, between the work of artists.”

Wild Life is also an opportunity for the museum to suggest new avenues for understanding both art history and contemporary art.

“Art history doesn’t fall from the sky,” says Matalon. “It’s up to us as art workers to shed new light on and bring new interpretations to narratives that have excluded women and artists of color.”

Crosby adds that opening up these narratives provides a powerful experience for museum visitors. “There is no shortage of new stories to be told, of lives dedicated to art,” he says. “Reaves and Murray are both incredibly bold artists who have rethought the very basis of the mediums in which they work. I find it very freeing to explore the horizons of possibility they have created with their art.”

Presenting sponsorship for Wild Life: Elizabeth Murray & Jessi Reaves has been provided by Agnes Gund.

Generous support for Carnegie Museum of Art’s presentation is provided by The Susan J. and Martin G. McGuinn Exhibition Fund.