|

||||||||||

St. Mary’s Lake reflects the beauty and expansiveness of Montana’s Glacier National Park.Photos Courtesy of Macgillivray Freeman Films |

The Adventure Continues

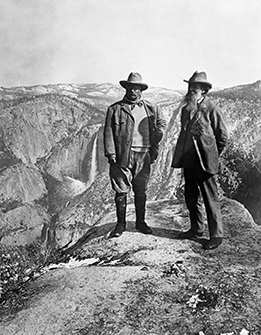

A cinematic road trip now playing at Carnegie Science Center celebrates the rush, relevancy, and advocacy of today’s national park experience. President Obama dined on salmon pre-chewed by a bear while hiking Alaska’s Kenai Fjord with survivalist reality-TV star Bear Grylls. Calvin Coolidge finally learned how to cast a fishing lure in the South Dakota Badlands. Theodore Roosevelt, camping in Yosemite, woke to find himself and his distinguished companion, John Muir, covered in a blanket of fresh snow.

Presidents aren’t the only visitors to create indelible memories in America’s national parks. Pristine, inspiring, and occasionally overrun, some 84 million acres of protected wilderness and historic places hosted a record-breaking 307.2 million sightseers in 2015. Locally, Carnegie Science Center is celebrating the centennial of the National Park Service, a major milestone in the preservation of the country’s natural wonders, by screening National Parks Adventure. Directed by veteran IMAX documentarian Greg MacGillivray and narrated by Robert Redford, who fell in love with Yosemite at age 11 while recovering from a mild case of polio, it honors the spirit of hundreds of iconic landmarks and natural playgrounds. While past accounts, including the popular 2009 PBS series by Ken Burns, have explored the parks’ history, National Parks Adventure salutes the modern park experience. It’s a sweeping, at times heart-pounding, glimpse inside the ice-climbing, Mesa mountain biking, and big-game escapades of a trio of extreme adventurers, whose thrilling quests suggest that there’s enough unexplored territory to last a few more centuries. It’s also one of the last giant-screen motion pictures to be shot fully in 70mm film, giving due justice to nature’s daunting scale and wondrous beauty. “Keep close to nature's heart ... and break clear away, once in a while, and climb a mountain or spend a week in the woods. Wash your spirit clean.”

- POET AND CONSERVATIONIST JOHN MUIRMax Lowe, one of the three explorers featured in the 45-minute film, hails from Bozeman, Montana. Growing up in Grand Tetons National Park gave the 27-year-old athlete and photographer a heartfelt appreciation for the parks’ eternal appeal. “In our parks, you can have a full-body experience—smelling fresher air, enjoying the sights and sounds. It’s fully immersive. That’s what captivates me,” he explains. “The experience gives us an emotional connection to place.” Lowe’s daredevil climbing and biking evoke a joyous, visceral thrill for viewers. While the film lavishes attention on some of the most celebrated western parks— Yosemite, Yellowstone, and Utah’s “Mighty Five” of Zion, Bryce Canyon, Arches, Canyonlands, and Capitol Reef—the park service also protects wonders that stretch across the country, including 19 sites in Pennsylvania. Well-known locales include Shanksville’s Flight 93 National Memorial, Johnstown Flood National Memorial, the Allegheny Portage Railroad National Historic Site, Fort Necessity National Battlefield, Gettysburg National Military Park, Philadelphia’s Independence National Historical Park, and nearby Valley Forge National Historical Park. “Let this great wonder of nature remain as it now is. You cannot improve on it. But what you can do is keep it for your children, your children’s children, and all who come after you, as the one great sight which every American should see.”

- TEDDY ROOSEVELTIn all, there are more than 400 sites— including lakeshores, seashores, recreation areas, scenic rivers and trails, and the White House—cared for by the federal agency. The most visited in 2015 (and every year since 1946): the Blue Ridge Parkway, which weaves through parts of Virginia and western North Carolina to the Smokies in Tennessee and is known as “America's favorite drive.” The most traveled national parks, in order of popularity: the Great Smoky Mountains (in a landslide), Grand Canyon, Rocky Mountain, Yosemite, Yellowstone, and Zion. Some 40 parks from coast to coast earn awe-inspiring screen time in National Parks Adventure, a few of which are likely to be completely new names to audiences.

“One of our researchers came up with this remote, absolutely amazing-looking park hiding on the shore of Lake Superior in upper Michigan,” says director Greg MacGillivray of Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, where the crew headed after the plan to shoot winter scenes in Yellowstone fell through due to the lack of snow. “Even the park staff out there were like, ‘Really? You wanna come film us?’” MacGillivray told local reporters. “But it turned out to be one of the most magical places.” KEEP IT FOR YOUR CHILDREN'S CHILDRENTeddy Roosevelt was a New York City kid who grew up to be a rancher, hunter, and the country’s preservationist-in-chief. He was not the first president to create a park; that was Ulyssess S. Grant with Yellowstone in 1872. Nor did he found the park service; that was Woodrow Wilson in 1916. But Roosevelt captured the nation’s imagination as a passionate orator and writer on the country’s magnificent landscape. “Let this great wonder of nature remain as it now is,” he famously declared in a ceremony protecting the Grand Canyon as a park in 1908. “You cannot improve on it. But what you can do is keep it for your children, your children’s children, and all who come after you, as the one great sight which every American should see.”

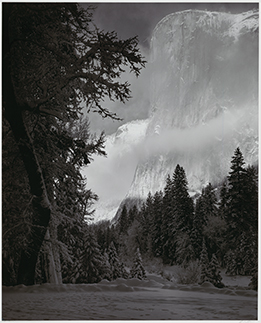

Carnegie Museum of Art’s collection includes iconic images of national parks and western landscapes by American artists striving to capture their beauty. Thomas Moran, who painted the geysers of Yellowstone in 1871, nearly despaired, calling the area “beyond the reach of human art.” He prevailed; his sketches and illustrations were instrumental in persuading Congress to declare the region the first national park. Painter and writer George Catlin documented the Native American cultures of the Plains. Ansel Adams, one of the most celebrated photographers of the 20th century, portrayed the stark beauty of the montane west, particularly Yosemite. He started photographing the park during a family vacation in 1916. The museum’s collection includes a stunning image by Adams of El Capitan (at right) taken in the winter of 1968 as well as an earlier image capturing the majestic sweep of the Yosemite Valley enveloped in the clear air and bright light of the High Sierra. Widely reproduced, Adams’ “visual diary” deepened public appreciation of the parks. But it was Scotsman John Muir’s paeans to the Sierras—which he so eloquently described as the “Range of Light”— that laid the foundations for the park service and 20th-century ecological awareness. Muir was more than the founder of the Sierra Club, now the nation’s largest and most influential grassroots environmental organization. He was its patron saint, preaching the gospel of conservation until his death in 1914. His most famous disciple was, of course, Roosevelt. Reenacted in National Parks Adventure, it was the pair’s 1903 three-day visit to Yosemite’s snowblanketed Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias and the Yosemite Valley that is widely known as “the most significant camping trip in conservation history.” According to the National Park Service, Roosevelt’s executive orders preserved nearly 230 million acres of land, roughly the size of the Eastern Seaboard, from Maine to Florida. He set aside 150 national forests, the first 51 federal bird reserves, five national parks, the first 18 national monuments, the first four national game preserves, and the first 24 irrigation projects. While later presidents followed suit, it was Roosevelt’s cousin, Franklin, who most expanded the park system and its mission. FDR brought historic sites under the park service, marshaled the Civilian Conservation Corps to maintain the parks during the Depression, and created Olympic, Great Smoky Mountains, and Kings Canyon National Parks.

As it observes its 100th birthday, the Park Service is debating how to continue its mission to conserve wild species and places while guaranteeing universal access to all. Some parks are now struggling with traffic and air pollution as millions of cars and motorhomes pass through. In response, Zion National Park instituted a mandatory shuttle bus system for all visitors. Dangerous human-animal encounters, including the deaths of two visitors mauled by bears in Yellowstone in 2012, have prompted worries that visitors are getting too close to nature. The system also faces $12 billion in costs for overdue infrastructure maintenance. Given the challenges, this year’s centennial is tempered by the realization that the beloved parks need continued vigilance and investment from those that love them. And a new 25-year master plan calls for the system to redouble its efforts to promote biodiversity —as well as diversity among human visitors. “In many ways, the National Park Service is our nation’s Department of Heritage,” the report observes, requiring renewed efforts in education as well as conservation. To explorer Max Lowe, the importance of the national parks is patriotic, natural, and spiritual. “The national parks exist within our society because they have value,” he says. “The National Park Service is the voice of wild places for the majority of us who live in cities. Our desire to protect the parks is evidence of the enduring beauty of place.” National Parks Adventure is sponsored locally by Baierl Subaru.

|

|||||||||

Ai Weiwei at The Warhol · Window into the Wild · Backyard Science · Special Section: Tribute to Our Donors · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Eric Dorfman · Artistic License: After Hours · Science & Nature: Teacher's Aide · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |