|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

One of Ai Weiwei’s most famous works is the 1995 performance Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, which is documented in this triptych. The work not only began the artist’s continuing reuse of antique ready-made objects, it also demonstrates his questioning attitude towards cultural values and social history.Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995, image courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio, © Ai Weiwei |

Ai Weiwei at the Warhol

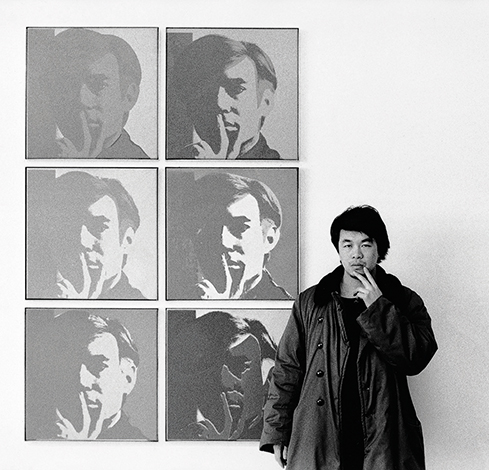

It was only a matter of time before the famed Chinese artist-activist would exhibit alongside one of his earliest artistic inspirations. Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei opens June 4 at The Warhol. In 1983, Ai Weiwei (pronounced eye wayway) arrived in New York City to soak up American contemporary culture, a freewheeling contrast to the repression in his native China. The 26-year-old unknown artist attended a few art openings where he happened to spot Andy Warhol across the room. An outsider who spoke imperfect English, Ai was too shy to approach the American Pop-art superstar who utterly fascinated him. Even so, Ai could feel Warhol’s aura in the room and it seemed to follow him around New York, where he lived for the next decade. “Warhol was in the air,” Ai would later say.

Quietly defying the Communist state, Ai set in motion an underground arts culture. Over the next two decades, he transformed himself into the most famous artist-activist in the world, achieving a Warholian celebrity status as he spread his creative energy and causes to hundreds of thousands of fans around the world who follow him on social media. His fame as a dissident artist only heightened when he was placed on house arrest in 2010 and detained illegally for 81 days the following year. Ai has always been inspired by the American artist who died 29 years ago but was decades ahead of his time. “To me, Warhol always remained the most interesting figure in American art,” Ai says.

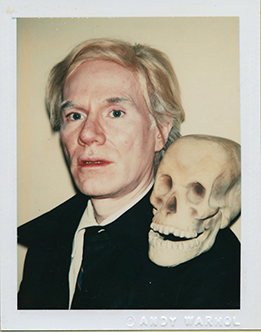

The parallels and intersections of these two unlikely kindred spirits fuel Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei, a buzz-generating exhibition on view June 4 through August 28 at The Andy Warhol Museum. Organized by The Warhol in partnership with the National Gallery of Victoria, the first-of-its-kind exhibition made its December debut in Australia, drawing record-breaking crowds. Ai, now 58, is expected to come to Pittsburgh for the opening of the show, which includes 200 works by the pair, juxtaposed on every floor of the museum. Their backgrounds could not be more different: Warhol grew up in working-class Pittsburgh as part of an Eastern European family and lost his father at age 14; Ai and his parents spent the artist’s childhood and formative years in exile, banished to several remote labor camps, the last at the edge of the Gobi Desert, where they lived for 16 years. But each grew naturally into their roles as creative agitators challenging the status quo. Ai is still challenging it, now as a celebrity-artist bringing attention to the plight of the refugees fleeing Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya and washing up on the Greek island of Lesbos, where he set up a studio earlier this year. “It’s the most important show we’ve ever done,” says Eric Shiner, director of The Andy Warhol Museum. “It has so much weight to it now, especially with Weiwei’s steadfast dedication and focus on the refugee crisis.” Though Ai is more overtly political than Warhol ever was—though works like Electric Chair and Race Riot were powerful insights into the culture of Warhol’s time—both used their art as a means of dissent and redefined contemporary culture. “Being gay, being underground, Warhol was an outsider who perfectly delivered the reality of his time and became the author, in so many ways, of late 20th-century America,” Shiner says. “He has since gone on to be the representative of that period of America, just as Weiwei —outsider, rebel—will stand as the representative of China at this moment in time in so many ways. Weiwei will be just as iconic as Warhol is today.” OBSESSIVE OBSERVERSBefore the Internet, before Twitter, and before reality TV, Andy Warhol obsessively documented his life— including everyone and everything around him—by taking Polaroids, shooting films, publishing books, even recording everyday phone conversations. In an interview with Shiner, Ai said he has always been fascinated by Warhol’s “desperation to communicate, as evidenced by his films and publications such as Interview.” In fact, as a young man in New York City, the first book that Ai bought was a signed copy of The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again). Decades later, Ai’s own thoughts were immortalized in a book titled Weiwei-isms. The artist also documents his life in the real time of the 21st century, taking selfies and transmitting his messages out to his growing legion of Instagram, Twitter, and Weibo (the biggest social network in China) followers. “[The Internet] totally changed my situation because, finally, I found this most precious gift that allowed somebody like me, who had already lost all hope to communicate, a new opportunity to express myself.”

- AI WEIWEIIt all began in 2005 when he started blogging, an occasion that changed his life, and his practice. “[The Internet] totally changed my situation because, finally, I found this most precious gift that allowed somebody like me, who had already lost all hope to communicate, a new opportunity to express myself.” He spent day and night online, and it was in those moments, says Ai, “when I felt closest to Warhol.” Ai’s fame skyrocketed in 2009, when he made a series of impassioned blog posts about the shoddy schoolhouse construction that claimed the lives of 5,000 children during the Sichuan earthquake a year earlier, a detail the Chinese government chose to suppress. He listed the children’s names on social media and referenced the disaster in his work. As a result, he was brutally beaten by government police—sharing hospital images with the world as proof—and later imprisoned. “Weiwei is constantly taking photos and recording you, almost nonstop,” says Shiner, who has visited the artist in his suburban Beijing studio multiple times. “I don’t think any two artists have ever been so obsessed with documenting their daily activities as Warhol and Ai.” The exhibition pairs two films by the artists that document their surroundings: Ai’s 10-hour film of the Ring Road in Beijing and Warhol’s eight-hour film of the Empire State Building. “The Empire State Building is a vertical cross section of New York, and Weiwei’s film is a horizontal cross section of Beijing. They are very different but they come from a similar place,” Shiner says. “I think viewers will find it fun to sit there and watch what happens in the streets of Beijing.” Both artists also developed their own studios, mass producing artwork while also nurturing their own community. Ai says he was inspired by The Factory, Warhol’s studio known not only for its silver walls and unique mass production of art; but also a culture all its own, with a long list of characters and personalities that came and went. “So many things happened in his studio,” says Ai. “He even got shot there. … The Factory was truly a melting pot. Warhol created his own society there.” Ai also has created his own society by setting up his Bejing studio, FAKE Design, where 30 young people from around the world conduct research, communication, and design work. “We are very productive and are more or less like a family. We have about 20 cats and a couple of dogs,” Ai says. “We receive many visitors, from university students and local artists to activists and art lovers.” But FAKE can’t be as open as The Factory. “Around my studio, there are 15 to 20 surveillance cameras,” Ai says. “Often there are police parked nearby. Our Internet is monitored and our phones are tapped.” Not surprisingly, political repression is a prominent theme in the Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei show. In one gallery hangs Warhol’s wallpaper of the Washington Monument, a backdrop for Warhol’s 13 Most Wanted Men, and a controversial collage of wellknown criminals of 1962 that he created for the New York World’s Fair in 1964, only to have it painted over by fair officials a few days after its installation. That lineup is juxtaposed with Ai’s mug shots of Chinese radicals who have all gone under house arrest. Nearby, Ai’s marble Surveillance Camera (2010) and jade Handcuffs (2011) stand as symbols of the police state filtered through his artistic lens.

Based on these blooms, Ai created Flowers for Freedom, a huge photo mural of colorful bouquets. Visitors will find the second floor of The Warhol entirely devoted to flowers—from a large porcelain flower installation by Ai to Warhol’s many well-known floral silkscreens and drawings. On July 22, 2015, the Chinese government finally returned Ai’s passport.

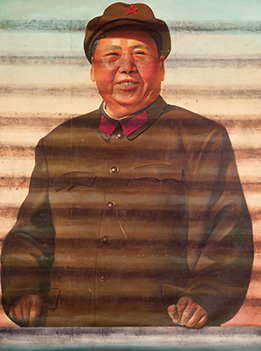

In a series of photos titled Study of Perspective, shot between 1995 and 2003, Ai flips the proverbial bird at some of the world’s best-known landmarks—Tiananmen Square and the White House among them. Ai says repetition “gives work a stronger position, and it makes the impression double and triple ... Because we live in a post-industrial information age, information is repeatedly re-used to establish a ground for communication.” READYMADE POLITICSOther pairings have direct references. Warhol’s various paintings of Coca-Cola bottles are hung near Ai’s famous Neolithic vase that he emblazoned with the Coca-Cola logo. “He questions what we value in society, what we call culture. What is more important—a ceramic urn that is hundreds of years old or a work of contemporary art?” Shiner notes. “By painting the Coca-Cola logo on it, he says maybe we think contemporary art is more important. Ancient art is valuable but not nearly as valuable as when he paints the Coca-Cola logo on it.” One gallery includes Warhol’s colorful silkscreens of Mao, made by utilizing the dictator’s portrait in his famous Little Red Book, which contrast with Ai’s less benevolent images of Mao, created in the 1980s. “Warhol viewed Mao as a world celebrity, on the front page of the news, a powerful leader,” says Shiner. “Weiwei, of course, has a different view of Mao as a destroyer of culture.” Ai was just a year old when the government sent his father off to labor mines in rural western China, and at one point the family lived in a small hole in the ground. Ai remembers how his father, who was trained as a painter but took up poetry when he was forced to go without paints, had to clean filthy toilets, and yet worked hard at making them spotless. “I really respected my father as someone who was highly aesthetically trained and lived and breathed poetry, but at the same time handled the most lowly and brutal work and never complained.” Occasionally described as the new Marcel Duchamp, another one of his artistic heroes, Ai acknowledges that both he and Warhol owe the artist a debt of gratitude. Among his other avant-garde creations, the French- American painter and sculptor was known for his found objects, or “readymade,” artwork. “Duchamp had the bicycle wheel, Warhol has the image of Mao,” says Ai. “I have a totalitarian regime: that is my readymade.”

“Warhol, in many ways, created a fake world, a fake Hollywood, a fake culture of his own universe,” says Shiner. “Weiwei, too, loves the idea of fake.” His most famous fakes are the Circle of Animals/ Zodiac Heads, 12 figures of the traditional Chinese zodiac, cast in bronze. This iconic work—on view at Carnegie Museum of Art’s Hall of Architecture through August 29 as a complement to The Warhol exhibition —is a reimagining of the figures that once adorned the famed fountain-clock of Yuanming Yuan, an imperial Beijing retreat that was looted by the British in 1860. Regarded as important national symbols, the Chinese government demanded their return to China when two of the original figures from the estate of Yves St. Laurent went up for sale in Western auction houses, selling for $5.4 million. Ai, who not surprisingly challenges his government’s support of cultural history, is quick to point out the original figures upon which he based his sculptures were not, in fact, Chinese, but rather created by an Italian sculptor. “It’s the most important show we’ve ever done. It has so much weight to it now, especially with Weiwei’s steadfast dedication and focus on the refugee crisis.”

- ERIC SHINER, DIRECTOR OF THE WARHOLAs a devoted supporter of refugees arriving in Europe, Ai has been dogged in calling the world’s attention to the current refugee crisis through his work. In February, Ai wrapped his Zodiac Heads, on view in Prague, in the gold thermal blankets given to refugees to help them keep warm. His fervor led to a controversy when he had himself photographed as a corpse, his face in the sand, recreating the haunting image of a Syrian toddler whose lifeless body washed up on a beach in Turkey while fleeing to Greece in the fall of 2015. “People were stunned beyond belief; it created a backlash,” says Shiner. “Everyone was mad at him, saying it was in bad taste, was disrespectful. Yet it got everyone talking about the refugee crisis.” Standing with Ai, The Warhol covered his exhibited Surveillance Camera with an emergency blanket and shared the image on social media. Through the run of the show, the museum will also collaborate on related programming with City of Asylum, a North Side community of artist-activists that provides sanctuary to endangered literary writers. For all of the serious themes the two artists share, both show a whimsical sense of humor, including a love of cats. The exhibition includes cat wallpaper drawn by Ai and cat sketches by Warhol, who owned many cats— 25 of them named Sam and one named Blue Pussy. Ai says that while he found inspiration in Warhol’s work, it wasn’t a blueprint for his own radical way of seeing the world. “In some ways, we are similar,” Ai says. “We both enjoy metropolitan life and like to be involved in cultural activities. However, I never tried to copy what he did. He is the product of American culture and I am not.” For Shiner, the show encapsulates what The Warhol is all about. “We look at how Warhol started as an anomaly and became the paradigm, and that is exactly what Weiwei has done, and then some.” Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts, The Fine Foundation, and The Heinz Endowments, with additional support from Christopher Tsai and André Stockamp.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Window into the Wild · Backyard Science · The Adventure Continues · Special Section: Tribute to Our Donors · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Eric Dorfman · Artistic License: After Hours · Science & Nature: Teacher's Aide · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |