|

||||||||||||||||

|

Window into the Wild

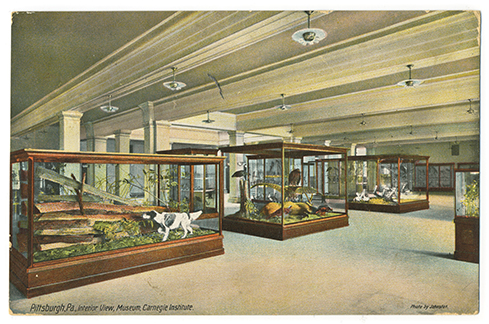

Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s world-class habitat dioramas, some built in the early 1900s, still wow today’s visitors. It was taxidermy that first drew Andrew Carnegie to the natural world, and to the idea of a natural history museum for Pittsburgh. While ordering a tiger-skin rug in Singapore, Carnegie struck up a conversation with a taxidermist who had just returned from a four-month adventure in Borneo collecting orangutans for a museum. Not long after the memorable encounter, the famous Scotsman made a contribution to the Society of American Taxidermists, believed to be his “very first gift to museology.” Fourteen years later—and a little more than a year after the November 1895 opening of his Carnegie Institute—Carnegie hired Frederic Webster, the first of many master taxidermists who had a hand in shaping today’s Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

To assist Webster, the museum hired Gustav Link, who helped mount many of its earliest animal groupings, including the dramatic display of a fallen elk, which still stops museumgoers in their tracks in today’s Hall of American Wildlife. Apparently killed by a Native American arrow, the elk, tongue out and lifeless, is surrounded by a menacing group of California condors and turkey vultures. “Millions of people have seen this elk, talked about it, pondered this scene,” says Steve Rogers, a longtime collection manager at the museum and a taxidermist. “That’s important because if you don’t know animals, you can’t love them.” Helping the public know and understand— even love—the natural world around them, and their place in it, is the sweet spot of natural history museums. They are, after all—by way of their massive collections, awe-inspiring exhibits, and cuttingedge research—nature’s record keepers. By the early 1900s, animal groupings in American museums advanced to full-blown habitat dioramas, taxidermy immersed in re-creations of the natural environments in which the animals were found. Sculpted rocks, plants, and earth, as well as curved background paintings, tell a biological story of a specific time and place, and blend the foreground seamlessly into the detailed background. The quality and quantity of these dioramas became the gold standard by which all great natural history museums were measured. Created in a time when photography was still new and travel was limited, dioramas have carried millions of museum visitors to other times and places.

At Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Link’s son, Gustav, Jr., also a museum preparator, took on the task of building the museum’s very first habitat dioramas with painted backgrounds. One of his earliest works features a Great Horned Owl, swooping down—talons at the ready—to snatch up a skunk. The curved background, depicting sunset in the wooded hills of Green County, Pennsylvania, and dramatized with low lighting, hints at the predator’s sharp night vision. Another display featuring large sea birds named red-footed boobies was inspired by an early Carnegie Museum expedition to Half Moon Cay, currently a national monument and bird sanctuary in Belize, at the time only reachable by steamer ship. These classic dioramas, along with five others built between 1923 and 1933, are back on view at the museum as the focus of a small exhibition titled The Art of the Diorama. Housed in a rear first-floor gallery fashioned much like a Victorian museum— complete with a chandelier, mahogany furniture, and a pair of bubble-glass mini-dioramas that were popular as home décor—their craftsmanship takes center stage. A pair of female artists previously unrecognized for their contributions, Anna Dierdorf and Hannah von Fuerhrer (the wife of the museum’s longtime chief artist Ottmar von Fuerhrer), are credited with creating much of the vegetation. “They’re beautiful works of art made at the height of their craft,” says Becca Shreckengast, Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s director of exhibition experience. “They spent three-quarters of a year or an entire year of work on each of them,” says Rogers. “Even after all of these years, these dioramas rival the best work anywhere.”

AS RELEVANT AS EVER

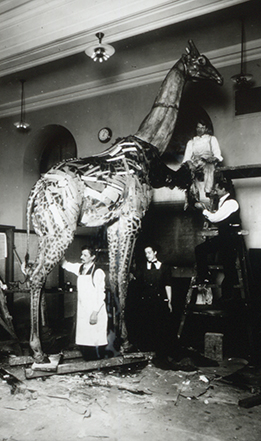

In the early 20th century, dioramas were considered so vital that museums continued to invest in them through the lean years of the Depression. But interest began waning after World War II, and by the late 1990s, about the time the Internet started to explode, dioramas fell out of favor in a big way. In 1999, Willard Boyd, former president of Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History, wrote that dioramas “are often viewed by today’s visitors as a dead zoo located in a dark tunnel.” Some museums, most notably the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, ditched many of their habitat dioramas for electronic interactives and stand-alone specimens. Others continue to question the usefulness of these aging displays, but Carnegie Museum of Natural History isn’t among them. The museum debuted its new Hall of African Wildlife to much acclaim in 1993 using taxidermy mounts created for the museum between 1910 and 1920 by brothers and master taxidermists Remi and Joseph Santens. Their work reflects a knowledge of anatomy and artistic skill unrivaled today. Two years later in 1995, the museum renovated its Hall of North American Wildlife, which features 16 habitat dioramas that include nearly 100 years of specimen acquisitions. “Our dioramas absolutely speak to the 21st- and 22nd-century audience. They’re every bit as relevant as the day they went in. What makes them so is how we use them.”

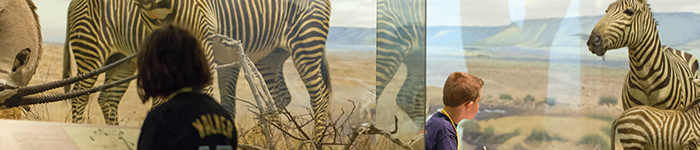

- ERIC DORFMAN, DIRECTOR, CARNEGIE MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORYThis level of quality sometimes demanded armies of volunteers to work alongside taxidermists and muralists. For the Alaskan moose diorama, a committee of women volunteers donated 1,100 hours to create perfect faux leaves for its alders (2,000 leaves), willow (1,800), and cranberry (3,200 for one bush). “Our dioramas absolutely speak to the 21st- and 22nd-century audience,” says museum director Eric Dorfman. “They’re every bit as relevant as the day they went in. What makes them so is how we use them.” Take the “seek and find” element added to the dioramas in Botany Hall that encourage visitors to spy, for instance, the Red Admiral butterfly or Virginia Bluebell. Or consider the brand new “In the Field” mural in the Hall of American Wildlife that features a stream that winds through Powdermill Nature Reserve, the museum’s biological field station in the Laurel Highlands. Nearby, clipboards and pencils encourage visitors to go on a field excursion of their own, looking closely not only at the plants and wildlife in the mural, but in the neighboring white-tailed deer diorama also set in the Laurel Highlands. “My hope is that we will encourage people to visit Powdermill and have a real wildlife experience, where their enthusiasm and level of knowledge has been augmented by what’s here at the museum,” says Dorfman. He’s not alone in this renewed interest in dioramas. In 2015, Chicago’s Field Museum crowdfunded $155,000 in just six weeks to construct its first new diorama in more than 60 years, using animals mounted in 1899. A few years earlier, the American Museum of Natural History spent $2.5 million restoring its popular Hall of North American Mammals. What’s more, climate change and other environmental threats present opportunities to make dioramas more relevant than ever. At Carnegie Museum of Natural History, blurring the boundaries between visitor and diorama—with a touch of theatrics thrown in—is the wave of the future, says Dorfman, pointing to the mood and storytelling of The Art of the Diorama. Perhaps the museum’s most successful example, he says, is the watering hole diorama in the museum’s Hall of African Wildlife, with its touchable bronze warthog, a leopard perched in a tree above visitors’ heads, and the sounds of birds filling the gallery. “We want drama that will give you, I hope, the same kind of gut-level response that people in the earliest days of this museum would have had just by seeing the objects alone,” he says. “My approach is inspired by the European Gothic cathedrals with vaulted ceilings and stained-glass windows,” he adds. “Many people in the Gothic period could not read, just like many of our visitors cannot read because they’re too young. I hadn’t been at the museum very long when I saw a young boy about 3 years old take what was clearly his first look at Tyrannosaurus rex. He looked up and said, simply, ‘Wooooow!’ And I want to bottle that.” A PITTSBURGH FAVORITEDioramas can create impressions that last a lifetime— or several. Generations of Pittsburghers have been equally wowed, frightened, and fascinated by Arab Courier Attacked by Lions, which depicts a knife-wielding North African camel rider fighting off a pair of now-extinct Barbary lions, one of which rests dead on the ground. The dramatic display won a gold medal at the Paris Exposition of 1867 and was hailed as a major advance in taxidermy. It was purchased by the American Museum of Natural History in New York, where it was wildly popular, but museum administrators ultimately considered it light on science and made plans to discard it. Recognizing its artistic worth, Carnegie Museum’s Webster rescued the Arab Courier, paying between $25 and $50 for it in 1899. Once it arrived in Pittsburgh, Webster and the older Link gave the display new life, replacing the camel driver’s damaged right hand, which grasped the knife, with a plaster cast of Link’s hand.

By year’s end, the museum will restore and reinterpret the signature exhibit and build for it a new heritage-style case, all in preparation for its move to a more prominent location on the museum’s first floor, where Jane, the juvenile T. rex cast, now stands. Jane will relocate to the museum’s gift shop, which will eventually double in size. “The Arab Courier is our second most famous object next to Dippy, so it should have pride of place,” says Dorfman. “In many ways, it’s as much a piece of art and cultural interpretation as it is a piece of natural history. To put it in a space that is shared between art and natural history celebrates the interplay between our two museums that share a building.” Shreckengast and team plan to have a CT scan performed on the camel driver’s head to confirm whether or not real human remains were used in the display that’s considered romantic “Orientalism,”which had its heyday in the mid-to late 19th-century.

“It’s a real treasure of the Carnegie, and we’d like to give it more context,” says Shreckengast, noting that it was rare even in the mid-1800s to use human remains in dioramas, a fact that the new signage will make clear in explaining the evolving methods used by taxidermists.

Looking ahead to next spring, Shreckengast also plans to bring out of storage many of the museum’s Paleozoic dioramas, built in the 1950s and ‘60s by an outside firm. Representing a time when plants became widespread and the first vertebrates were colonizing land, these displays will be housed in newly-built cases on the Foster Overlook, just above the Jurassic superstars of Dinosaurs in Their Time. THE HUMAN FACTOROften with their noses pressed against the glass that separates them from their favorite diorama, children ask: “Are these animals real?” Yes, parents respond. “So, they’re dead?” Yes. “Why?” That answer, it seems, doesn’t always come as quickly, or as confidently. “Lots of important conversations happen around dioramas.”

- BECCA SHRECKENGAST, CARNEGIE MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY’S DIRECTOR OF EXHIBITION EXPERIENCE“Lots of important conversations happen around dioramas,” says Shreckengast. “As educators, we need to introduce tools that facilitate discussions about conservation and about why there are dead animals on display. Because we’re not always doing this, we’re not part of that conversation, and we want to be.” Museum professionals consider the hunters who collected and donated many of the animals on view at the museum conservationists because they not only had an interest in the animals they tracked, but they supported expanded scientific understanding of the animals for their ultimate preservation. Standing in front of the early Elk diorama in the Hall of American Wildlife, Shreckengast points out how many of the museum’s dioramas were built about 50 years after the Industrial Revolution. “I think people were really reacting to the fact that nature as they knew it was disappearing,” she says. “But in all of the dioramas from that time, except this one, it’s almost as if humans didn’t exist. They’re pristine environments with no signs of human impact.” With climate change and other pressing environmental challenges facing today’s planet, Shreckengast suspects today’s audiences are feeling that same desire to reconnect with nature. This is where the museum and its dioramas could help deepen discussions around conservation. “Whether or not we are showing humans affecting these worlds is the next conversation about dioramas that we need to have,” she says. “We want and need to show human impact, and if we create anything new, we will.” What might this look like? Trash in the corner of a diorama, perhaps, or Christmas tinsel woven into a bird’s nest, says Shreckengast. She’s seen a few of these dioramas at other museums—a display of deer with a fence painted in, showing that their path had been stopped—but not many, at least not yet. It’s just as important, Shreckengast and Dorfman agree, to give that counterpoint between what the world was like in the 1920s and 1930s and today. “There’s a place for us to be at the forefront of the interpretation of the diorama; of bringing it to the next level,” says Dorfman, pointing to the subtle but effective blurring of boundaries and layering of stories in The Art of the Diorama. “We can contextualize objects in a way that doesn’t always require words on a wall.”

|

||||||||||||||||

Ai Weiwei at The Warhol · Backyard Science · The Adventure Continues · Special Section: Tribute to Our Donors · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Eric Dorfman · Artistic License: After Hours · Science & Nature: Teacher's Aide · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |