|

||||||||||||||||||||

Doug Aitken, Migration, 2008, 4-projection outdoor video installation; Courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York; Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich; Victoria Miro Gallery, London; and Regen Projects, Los Angeles |

What is Contemporary?

This past November, I introduced myself as the curator of the 57th Carnegie International by asking “What is Contemporary?” in a public lecture. It’s a question I have been posing over the past 10 years in the form of annual talks, and one I will have yet to answer as long as contemporary art continues to be a vital way to experience the world today.

Once one of a relatively small number of big shows to routinely survey the latest developments in art from North America, Western Europe, and Latin America, the Carnegie International now takes place amidst a proliferation of exhibitions happening worldwide. From Dakar to Sharjah to Mercosul to Beijing, the ambitions that first prompted Pittsburgh to position itself as a city of cultural aspirations are now shared globally. The scope of the International has also correspondingly grown, as artists work and participate in a seemingly boundless art world.

As I approached the question again, this time as curator of the next Carnegie International, I decided to narrow the scope of the field to recent past Internationals. My reasons were twofold. First, what better way for the Carnegie International team—assisting at every step are Allison Miller and Liz Park —to learn about the history we are building on? Preparing for this talk was an immersive crash course in the works of art, big ideas, catalogues, events, online life, and swag that have made each exhibition distinctive. (If you bought a set of the 2004 R. Crumb beer glasses from the museum shop, we envy you!) More significantly, this focus would begin to transmit a vision of the Internationals not as a series of one big show supplanting the next, but as a cumulative and ongoing look at art in a field that always stands to be seen anew. Starting in 1995, I have seen every iteration of the International, and when I think ahead to 2018, I like to imagine the invisible aggregate of past and future installations that the next International is contributing to. This compilation of “What is Contemporary?” helped me do just that. I begin, as I always do, with a declaration of terms. My manifesto. Contemporary art is by definition not yet history. And therefore has no established canons, clear-cut movements, or linear chronologies. It is driven by ideas and practices, not masters and mistresses, or masterpieces, or for that matter by mediums. Artists today can be painters and sculptors, but more than likely they deploy a wide range of mediums or no materials at all—whatever is the best form for expressing their particular concerns or ideas. To structure this wide-ranging question, I use 13 themes, which I have developed to generally encompass current issues and ideas. Ranging from TERRAIN to TECHNOLOGY, these themes offer interpretive inroads to the field of contemporary art and are by no means definitive. A work that falls under FLESH might as easily be discussed in terms of TERRAIN. For instance, when Allan McCollum blanketed the floor of the Hall of Sculpture with dinosaur bones in 1991, he essentially transformed the space into what looked like a dig site. But instead of TERRAIN, I chose FLESH to signal that which falls away and leaves us all bare bones—the museum truly as mausoleum. McCollum’s boneyard also gave me a chance to learn about one of the many unique collaborations that have taken place over the years between Carnegie Museums of Art and Natural History. The artist worked closely with Mary Dawson, curator emeritus of vertebrate paleontology, who selected these particular bones from the museum’s renowned collection to cast by the dozens for this massive installation. CONTEMPORARY ART IS DRIVEN BY IDEAS AND PRACTICES, NOT MASTERS AND MISTRESSES, OR MASTERPIECES, OR FOR THAT MATTER BY MEDIUMS.“When is Contemporary?” can be answeredmany ways. For this exploration, I look at the past 30 years, or the span of a generation of memory. Marked by the fall of the Berlin Wall, the start of the American culture wars, the uprising in Tiananmen Square, among other social and political events and upheavals worldwide, 1989 stands as a decisive year for contemporary culture at large. Since there was no International in 1989, a Carnegie-centric survey of “What is Contemporary?” stakes its start to the 1988 exhibition and ends with the most recent International held in 2013. Admittedly, I am partial to the idea that America’s oldest global survey has been contemporary from the start. (The Venice Biennale is older by a year, but Pittsburgh does famously have three more bridges.) Since 1896, the Carnegie has been showing and collecting the work of living artists, originally with the hopes that some would prove to be “the old masters of the future.” Therein lies the rub: that 19th-century rhetoric just doesn’t jibe with the idea of the contemporary—as a field, an awareness, a culture currently under construction. “What is Contemporary?” is a capacious format for exploring a question that I look forward to returning to throughout the process of organizing the 2018 International. For the first Pittsburgh delivery, the museum’s theater was happily packed with the International’s frontline audience—the local community. The talk moved quickly, as it must, to synthesize each year’s reflections on an unruly field. Afterward, snacks were served in the lobby, where pierogies were piled high, Arsenal cider flowed, and conversation roared. I took this din to signal a good start to making “What is Contemporary?” as alive a question to those of you who come to see the 57th International as it is to me.

A snapshot of the 13 themes and some of the corresponding artworks that frame Ingrid Schaffner's exploration of “What is Contemporary?” based on past Carnegie Internationals from 1988-2013.

TERRAINVisible only at night, Doug Aitken’s cinematic projection on the Forbes Avenue façade in 2008 was a surreal western in which an all-animal cast moved silently through the hotels, motels, and airports that have altered their native terrain.

SYSTEMSStill on view overhead in the Hall of Sculpture is Lothar Baumgarten’s 1988 inscription of letters for the Cherokee tongue that didn’t have a written system of language until the 19th century. REFERENCESometimes it’s easy to discern the references in Gerhard Richter’s 1988 paintings based on photographic reproductions; other times, it’s the act of mechanical reproduction itself that appears referenced in abstractions that read like layers and layers of mis-registered print. HISTORYIn 1999, Kara Walker’s charming, cinematic silhouettes unmasked race relations in a revised history of the South.

IDENTITYVisual activist Zanele Muholi, whose portraits were presented in 2013 (above), put an assured face on African LGBT communities. ALCHEMYTo fully experience the alchemy of Ernesto Neto’s 1999 environmental sculpture, you needed to enter the Nude Plasmic, smell the lavender, and let your awareness of the surroundings be transformed by materials. FLESHA drain in the chest of a fragmented torso could be peeked at through the bars of a grate in the floor, where Robert Gober’s 1995 sculpture was installed to give a contemporary view of the figure as flesh. STORAGEIn 1991, Christian Boltanski constructed an imaginary archive with an empty storage box for every artist who participated in a past International.

BUSINESSInstalled in 2008 in the museum’s grand staircase—where John Alexander White’s mural The Crowning of Labor holds sway—Cao Fei’s video Whose Utopia (above) imagined the interior lives and dreams of young people at work in the frenetic wake of business in Communist China.

FORMParticles of Lara Favaretto’s confetti cubes are still turning up the traces of her 2013 sculptures, which quickly went from being solid forms to material dispersions.

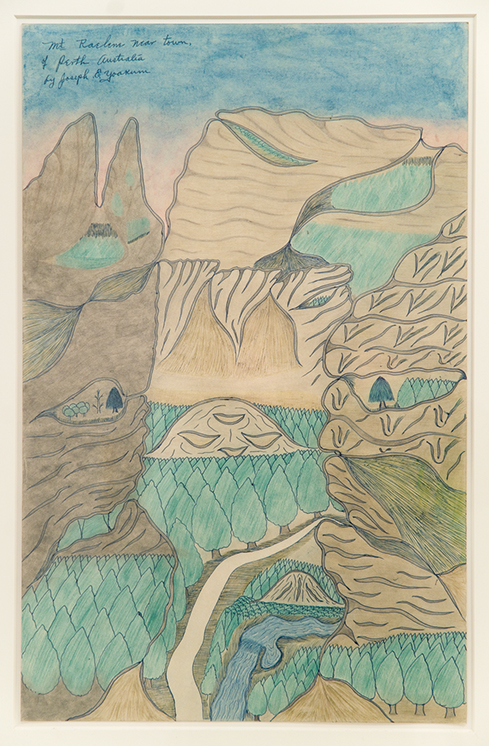

EVOCATIONIn the 1970s, when he was in his 70s, the visionary artist Joseph Yoakum started drawing an account of his world travels as conjured from memory as imaginative evocations of place. Shown in 2013, Yoakum’s work proves an artist doesn’t need to be living for their work to be alive to a contemporary point of view.

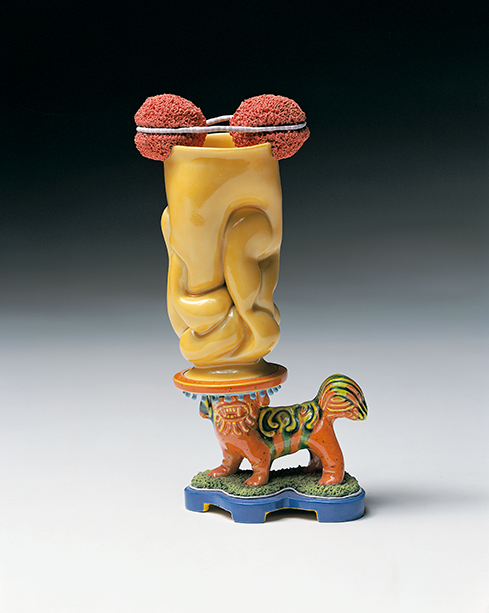

ORNAMENTThe craft of Kathy Butterly’s diminutive ceramic sculptures, shown in 2004, is as disarming as it is ornamental and decorative. TECHNOLOGYIn 2004, Harun Farocki’s Eye Machine evidenced 60 years of military assaults and otherwise almost invisible electronic surveillance and technology. RESISTANCEThe artists collective Transformazium took visitors to the 2013 International outside of the museum to the township of Braddock, where they are still energizing the community around art and the generative potential of working in resistance to mainstream approaches and venues. [The public can still borrow artwork from the Art Lending Collection at Braddock Carnegie Library.]

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Masters of the Mesozoic Sky · The Art Revival of Mr. Chow · Unseen · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Adil Mansoor · Artistic License: The Museum as Laboratory · First Person: Race Against Extinction · About Town: Awarding the Changemakers · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |