|

||||||||||||||||||||||

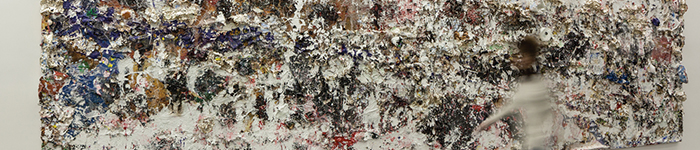

Installation view of Voice for My father.Photo: Courtesy of UCCA |

The Art Revival of Mr. Chow

The famous restaurateur returns to his roots as a painter, debuting his first U.S. exhibition at The Andy Warhol Museum.

As a young man, he channeled the pain over his lost culture into painting. He went on to study at Saint Martin’s School of Art and the Hammersmith School of Building and the Arts, both in London. While Chow enjoyed some early success, he says there was little support for a Chinese artist, and that he longed to promote his homeland to the West. So in 1968, in his late 20s, Chow put down his paintbrush and focused his artistic energies on opening Mr. Chow’s restaurant in London, an upscale Chinese restaurant known for its dramatic staging, original artwork, and celebrity clientele. After expanding his business to Beverly Hills, in 1979 Chow opened a third location in Midtown Manhattan, which instantly became an epicenter for artists. It was there he befriended Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, Julian Schnabel, and Jean- Michel Basquiat. Chow fed them Peking duck, bought their art, and commissioned Warhol and others to paint his portrait. Today the friendship between Warhol, the late king of Pop art born in Pittsburgh, and Chow, the avant-garde Chinese restaurateur, has come full circle. After a nearly 50-year hiatus, Chow began painting again, and his first U.S. exhibition is on view, fittingly, at The Andy Warhol Museum. Michael Chow aka Zhou Yinghua: Voice for My Father runs through May 8. The show draws parallels between the two talented friends, both self-made men. “Andy was 14 when he lost his father, roughly around the same time as Michael,” says Eric Shiner, director of The Warhol. “So, what does that mean as they paved their own ways? Does that compel or push or drive one to succeed?” Both men became brilliant marketers and businessmen. But Chow took a much more circuitous path as a painter—one that he believes has hurt him today. Becoming an artist is never easy, but try resurrecting such a dream in your 70s, following a career in restaurants. “The perception of me as a restaurateur is very, very high,” Chow says. “The perception of me as a painter is very, very low. They say no true artist can be a restaurateur, can be Chinese, can be old. But I will overcome that.”

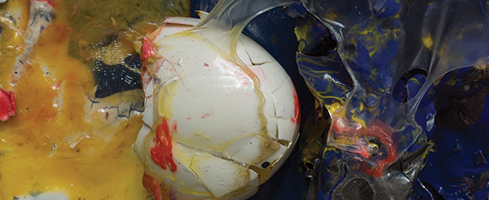

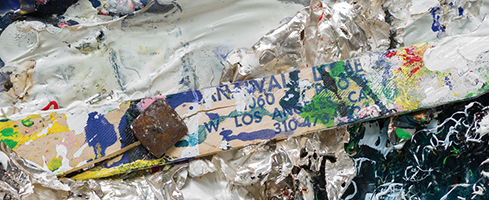

Shiner has heard from doubters, too. “When I first say we are doing a Michael Chow show, people are dismissive. They say, “Well, why would you do that? He’s a restaurateur.’ Or, ‘Is he really that good?’ But the paintings speak for themselves. I hope this exhibition cements him as the fantastic artist he is.” Inside his Los Angeles studio, Chow spends eight to10 hours a day painting, climbing up and down a ladder to create his massive works. It’s a good workout for a body that he says has become frail. Peering out of black owlish glasses, he paints and embeds egg yolks, gold leaf, paint lids, money sealed in plastic bags, sponges, and other items on his artwork, coating them with resin and giving the canvases a sculptural feel. “I am drowning in paint,” he quips.

Shiner says the large, collage-like abstract paintings work on several levels. “They are incredible and complex and textural and violent,” says Shiner. “They engage the visitor from afar as beautiful compositions—and then, as you are drawn closer, you really have to analyze them. You’re drawn into them because you want to start looking to see what you can find. So it becomes a bit of a scavenger hunt. “When you think of him as an art collector and as someone who’s constantly buying things, it’s interesting that it plays out in his paintings,” says Shiner, noting the recycled items jumping out of Chow’s canvases.

The exhibition also harks back to the artist’s idyllic youth in China, when he was known as Zhou Yinghua, a sickly boy with asthma who was pampered by servants. He adored his father, a legend in China who wrote more than 200 operas and performed some 600 roles during his 60-year career. Striking photos of his father performing in long robes and beard are central to the exhibition. They’re precious keepsakes for the son who never again saw his father, whom he later learned was not only tortured and imprisoned, but died while under house arrest during Mao’s Cultural Revolution. “All my life, I have been searching for my father, my culture, my country,” Chow says. His paintings are an homage to his father—a mix of Western and Eastern sensibilities, and of pain and optimism. “At age 12, I was devastated because I lost my culture,” he says. “Optimism comes from extreme pain.”

Befriending AndyThe exhibition also includes Chow’s wideranging collection of portraits of Chow himself, painted by other artists, including four by Warhol. Chow first saw Warhol’s work in the early 1960s. Still painting himself, Chow was a ticket taker at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. He was impressed with the Pop artist and was inspired to act. “I didn’t know Andy at the time personally, and I had the audacity to send him Polaroids of myself in 360 degrees, through a friend, and ask for a portrait.” But Warhol didn’t do it—at least not then. Later, when the pair became friends in the ’70s, they would laugh about Chow’s chutzpa. Warhol honored the request belatedly when he painted four portraits of Chow, his right arm under his chin, his stare straight-on. Chow bought two of the four paintings, each covered in “diamond” dust. After Warhol painted the images, the paint still wet, he would sprinkle them with finely ground glass to give them a glittering feel. He originally experimented with real diamonds, but deemed them too expensive. Chow later regretted not buying the other pair, painted in red and black, now part of The Warhol’s massive collection. “Andy would always make more, hoping clients would buy more, and when they didn’t sell, they would eventually come to us,” explains Shiner. Chow says he never discussed painting with Warhol. But artwork was all around him in his New York restaurant. “It was an old artist cafeteria—a very chic one,” he says. “[In the 1980s], Keith Haring had a birthday party at Mr. Chow’s. We had 106 bottles of Cristal champagne. We were very decadent back then.” “Every once in a while, an artist has been toiling away for years and then is recognized. But keep in mind, Michael wasn’t toiling away. he wasn’t painting; and then he decided to go back to it, and he hit it out of the park.”

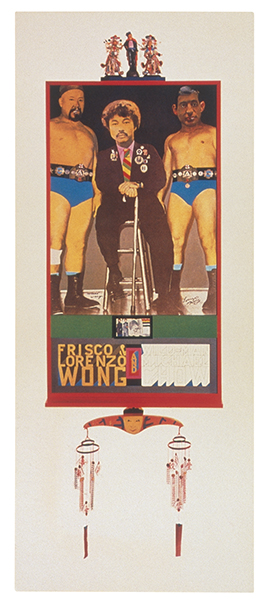

- ERIC SHINER, DIRECTOR OF THE WARHOLAlso part of the exhibition is the first portrait Chow commissioned, painted by his friend Peter Blake. Titled Frisco and Lorenzo Wong and Wildman Michael Chow, it depicts the restaurateur as a wrestlermanager with half-Chinese, half-Italian bodyguards. It hung in Chow’s London restaurant for decades. Another famous painting by Keith Haring, Mr. Chow as Green Prawn in a Bowl of Noodle, shows three green Chows wading enthusiastically in a bowl of noodles. A Successful Second ActThe celebrity artists were just one part of the scene at Mr. Chow’s. “Everyone from Mick Jagger to Twiggy seemed to be there,” says Bob Colacello, a Warhol biographer and former editor of Interview magazine. The celebrity clientele kept following Chow as he opened restaurants in Tribeca (the second New York location), Miami, and Malibu. Today there are seven locations, the most recent addition in Las Vegas.

“In the early 1990s, it went through a big hip-hop phase,” Colacello says. “It attracted a very mixed clientele, everyone from P. Diddy to Ron Perelman. There was this mix of celebrities, society, the art world, pretty young things, bright young things, pretty bright young things. What is amazing is that Michael has stayed on top and still is, in so many places. It’s really difficult to do that. Many restaurants start out as fashionable and get so much press that they are taken over by a less fashionable crowd.” He never made the menu nouvelle. “It was never gluten-free or sugar-free or fatfree,” says Colacello. “It’s fabulous fried parsley and Peking duck.” Chow never sang in the opera like his father, but he designed his restaurants as theatrical experiences, complete with a multi-level, stadium-style table arrangement perfect for people watching, tuxedoed waiters, and doors made out of original Lalique glass. Today, Chow’s wife, Eva, oversees the day-to-day operations of the restaurants, and he stays involved despite his devotion to painting. “I’m doing a long-running musical theater for 47 years,” he says. “My philosophy is to never bore the audience. A restaurant is not a business. It’s a theater. I never left being an artist.” Even so, he may never have expressed those feelings with a paintbrush again had it not been for the encouragement of Jeffrey Deitch, art dealer and former director of the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles. About five years ago, Deitch asked Chow if he would give a talk at the museum about the breadth of his artistic accomplishments— from architecture and design to collecting Art Deco and contemporary art. Deitch visited Chow’s house and happened to see a beautiful small painting against the wall. “What’s that?” Chows recalls him asking. “That’s mine,” Chow replied. He created the painting in 1962 and showed it at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. It was, coincidentally, a breakout year for Warhol, who had his first major solo Pop art show, Andy Warhol: Campbell’s Soup Cans, at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles. Deitch was struck by how the painting combined elements of the European avantgarde, American modernism a la Jackson Pollock, and Eastern art. “It’s amazing,” Deitch recalls thinking. Later, when Deitch was preparing a modern art show and showed Chow some of the work, the restaurateur told him, “I can do better than that.” “He plunged into painting. I remember him showing me his first work,” Deitch says. “It wasn’t modest. It was gigantic. He went all the way with full energy. It is a remarkable phenomenon after 50 years of not working on painting. He still had all his painterly skill and confidence.” But then again, Chow was not only trained in art and architecture; over the years, he’s absorbed so much simply by creating a chic hangout for artists. “Who else was friendly with Andy Warhol, Julian Schnabel, and Keith Haring?” Deitch asks. “He didn’t just look at people’s work. He had remarkable knowledge and firsthand engagement with art.” Shiner adds, “Every once in a while, an artist has been toiling away for years and then is recognized,” he says. “But keep in mind, Michael wasn’t toiling away. He wasn’t painting; and then he decided to go back to it, and he hit it out of the park.”

In 2015, Chow returned to China for the first time for the debut of Voice for My Father. It opened to huge adoring crowds in Beijing and Shanghai during the country’s week-long celebration of what would have been his father’s 120th birthday. After his death, his father was politically exonerated, and today is revered by the cultural establishment. Shiner heard about the exhibition and asked if he could put on a smaller version of the show in Pittsburgh. Chow was beyond thrilled. As he climbs up and down his ladder to create his large and sculptural paintings, Chow says he sometimes wonders to himself: What would Andy think of his work? His friend Bob Colacello, the Warhol biographer, thinks he has an idea. “‘Oh gee, Michael, I wish I would have thought of that. That’s really good. That’s so clever. “Oh wow, you used silver.’”

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

Masters of the Mesozoic Sky · Unseen · What is Contemporary? · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Adil Mansoor · Artistic License: The Museum as Laboratory · First Person: Race Against Extinction · About Town: Awarding the Changemakers · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |