|

||||||||||||

| Museum spaces & faces the public rarely sees.

Collectively, the four Carnegie Museums are the caretakers of more than 22 million scientific objects and specimens, nearly 43,000 works of art, a World War II submarine, and a 2,200-acre nature reserve. Each year, the museums host scores of camps and classes, and at least 150 special exhibitions, films, theater shows, and live performances. Helping to pull it all together: 1,047 staff members—a team of public-facing curators and scientists, educators and administrators, fundraisers and customer service staff. And all those who work behind the scenes—carpenters, conservators, and collection managers, art handlers and exhibit designers, bookkeepers, editors, and electricians, registrars, technologists, and more. Here’s a peek inside some remarkable, off-limits museum spaces and the staff members who power them.

Of the 30,243 works in the Museum of Art’s collection, 1,372 are paintings. Like most major collecting museums, the Museum of Art has a relatively small portion of its holdings—7 percent overall, 3 percent of its paintings—on view at any given time, with works routinely out on loan, rotating within the museum’s galleries, included in temporary exhibitions, and in storage. Added in 1974 as part of the Scaife wing, painting storage was built to allow for growth. “Staff at the time probably thought they’d never fill it,” says Elizabeth Tufts Brown, associate registrar for collections and archives. Today, paintings line 122 storage racks—each two-sided and measuring about 12 feet high and 10 feet wide, with a weight limit of 593 pounds. The museum added the racks in three stages, as the collection grew in number and the works grew in average size. Over 40 years, the number of paintings has grown by about 300, and many of the works from the ’70s and ’80s are quite large. Painting storage is now at capacity—housing 817 paintings, 142 sculptures, 101 framed photographs and prints, three textiles, and nearly 600 audio and video works—which is one reason the museum has undertaken its first major storage reorganization. Gabriela DiDonna and Tufts Brown are two of the museum’s four registrars, the official record keepers of the collection. They trail each work, making sure it stays safe as it travels within and outside of the museum. “Most people are familiar with university registrars,” says Orian Neumann, chief registrar. “Instead of tracking people, we track artwork.”

The name of the room refers to its size, not the size of its bones. That’s compared with the Little Bone Room just across the hall in the basement of the museum. Always locked, the Big Bone Room is located just around the corner from tracks used in the early 1900s to move boxcars full of dinosaur bones that were regularly shipped by train to the museum from Dinosaur National Monument in Utah, which yielded the greatest stockpile of Jurassic dinosaur bones ever found. Amy Henrici is one of eight collection managers caring for the museum’s 22 million objects and scientific specimens. The vertebrate paleontology collection she manages spans 465 million years and is the fourth largest in North America. It includes 79,464 catalogued specimens. And while it’s worldfamous for its sauropod (long-neck, plant-eating) dinosaurs, they account for only a small fraction of the collection’s impressive fossil holdings: 80 percent mammals, 11 percent fish, 5 percent reptiles (including 690 dinosaur fossils), 3 percent amphibians, and .5 percent birds. The collection also boasts 467 holotypes (the specimen the name is based on), including Diplodocus carnegii and Tyrannosaur rex. The first specimen to be logged: An Eocene fish fossil roughly 50 million years old from Wyoming, donated in 1896.

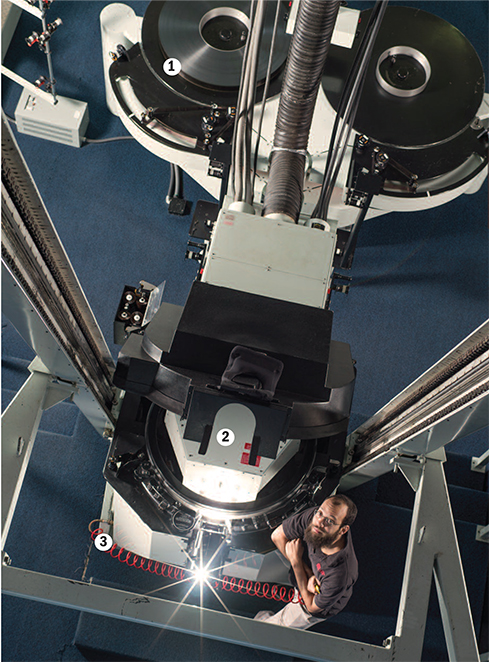

The Rangos Omnimax Theater, a four-story, IMAX® dome theater, is one of fewer than 50 remaining in North America. It's the biggest screen—and the only dome screen—in Pittsburgh. One of the things that makes it special is its rare use of 15/70 film, which is about 10 times larger than standard 35mm film, accounting for its amazing clarity. The IMAX projector is known for its unique “rolling loop,” which also contributes to the quality of the image. Films arrive at the Science Center in multiple reels, so projectionists splice them together—an intricate process of cutting and taping multiple rolls of film into one. Dark Knight Rises arrived in a record-setting 49 sections, taking staff about a week to stitch it together. The bulb for the projector is 15,000 watts—so bright that it could be seen with the naked eye from the moon! Because it’s filled with pressurized xenon gas, it could violently explode if dropped. That’s why three projectionists at a time, all wearing safety gear, are charged with changing it, a process that can take about three hours.

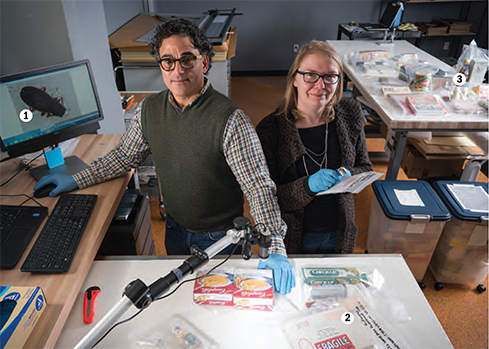

The Warhol’s conservation lab, housed in a space that was once the museum’s café, is hiding in plain sight. Tucked away on the museum’s underground level and operational for only a year, its glass wall doesn’t yet provide signage or other hints as to what’s happening inside. In this photograph, lining the table are the contents of one of 10 oversized isolation bins filled with objects from Andy Warhol’s Time Capsules—a collection of 610 cardboard boxes filled to the brim with keepsakes and ephemera from the artist’s everyday life. A sign taped to the lid of another reads, “Keep mummy foot on top.” Inside are items doublebagged and isolated from the boxes following a 2011 pest infestation of the museum’s archives. Because the contents of the Time Capsules— estimated at half a million objects—include such things as dog treats, cookies and cakes, cosmetics, soap, wool, hair, and even a mummified foot, they’d become a target for bugs. Tapping the expertise of entomologists at the Museum of Natural History, Amber Morgan and John Jacobs worked to identify three kinds of miniscule beetles that had infiltrated some of the Time Capsules, Warhol’s largest work of art. They then performed pest mitigation treatments and developed a museum-wide, integrated pest-management program, in the process making The Warhol a leader in contemporary art and archives management. “While an infestation is generally a bad thing, we were able to turn it into a positive by using it as a catalyst for developing a full preventative program,” says Morgan. “Our word of caution: you don’t know if you have an infestation unless you check.”

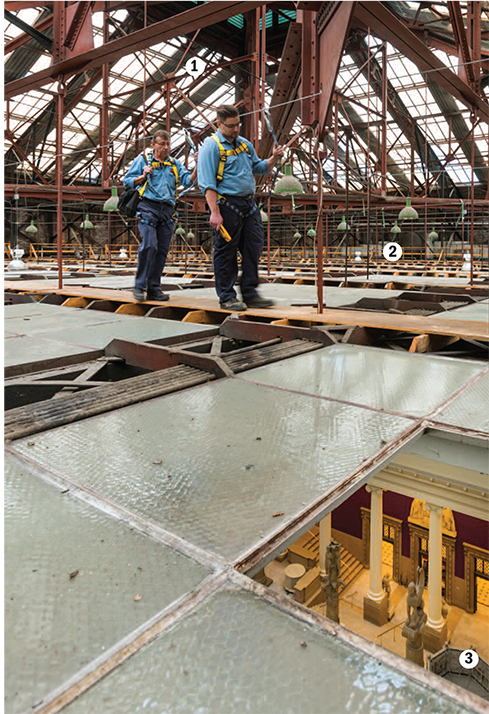

If you look closely at the glass-paned floor, you can catch a peek of Carnegie Museum of Art’s Hall of Architecture 68 feet below, aglow in natural light. The attic is the foundation for one of two glass cupolas, or small domes, adorning the building’s roof. While strapped into safety harnesses attached to a Carnegie-stamped steel beam, Tim Holewinski (rear) and Zach Johnston change light bulbs. In 1907, the Oakland facility became one of the first buildings in Pittsburgh to convert to direct current (DC) electricity. In 2015, all 4,000 incandescent bulbs in the building were replaced with LED bulbs, for an annual savings of $62,800. Leading this charge was the facilities, planning, and operations team, which maintains 40 buildings in southwestern Pennsylvania, including the historic Oakland facility built in 1895 by Andrew Carnegie.

|

||||||||||||

Masters of the Mesozoic Sky · The Art Revival of Mr. Chow · What is Contemporary? · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Adil Mansoor · Artistic License: The Museum as Laboratory · First Person: Race Against Extinction · About Town: Awarding the Changemakers · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |