|

||||||||||

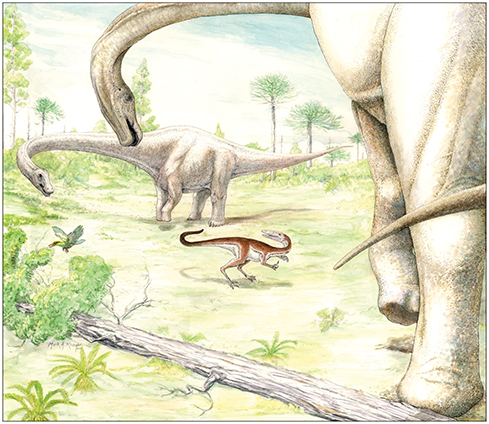

Above Illustration: Jennifer Hall |

Paleontologists have unearthed the most complete skeleton ever found of a super-massive dinosaur, providing the best glimpse yet of how these lumbering giants lived. At about the same time Tyrannosaurus rex was ruling the American West with ferocious force, a beast seven times its size reigned supreme south of the border in Argentina.

The unearthing of Dreadnoughtus schrani, a new super-massive dinosaur from southern Patagonia, doesn’t just make the menacing king of the tyrant lizards look puny. Measuring as long as a tennis court, weighing as much as a herd of African elephants, and standing two stories tall in life, the plant-eating powerhouse unveiled this past September is one of the largest land animals to ever walk the earth. It’s a discovery so colossal it took a team of paleontologists, including Carnegie Museum of Natural History dinosaur hunter Matt Lamanna, nine-plus years to excavate and study it. “Dreadnoughtus means ‘fearer of nothing,’” says Lamanna, noting that adults of the new species would have towered over predators at the end of the Age of Dinosaurs (between 84 and 66 million years ago) and, with a single swipe of their tails, clobbered the competition. “When you’re a behemoth the size of a whale—and you’ve got a brain the size of an apple—it’s probably just about impossible to feel any fear.” And if it had squared off against T. rex? “If this thing had simply leaned on T. rex, it would be game over,” Lamanna quips. Among the most giant and mysterious of dinosaurs, titanosaurs such as Dreadnoughtus were house-sized herbivores with tiny heads, long necks, hefty bodies, and tapering tails. They’re part of a group called sauropods, made famous in Pittsburgh by two stars of the Jurassic, Apatosaurus and Diplodocus, the latter affectionately known as Dippy. And at first glance, Dreadnoughtus looks like Dippy on steroids. But about 70 million years and a whole lot of bulk separate the two. “Their overall length and height would be pretty close, but their mass is where they would’ve differed considerably,” Lamanna explains. “You can think of the 15-ton Diplodocus as the wide receiver of the sauropod group, whereas the 65-ton Dreadnoughtus would be the offensive lineman.”

Most importantly, having more than 70 percent of the types of bones of Dreadnoughtus, excluding most of its head, opens an unprecedented window into the anatomy and lifestyle of the world’s largest dinosaurs. “It’s by far the best example we have of any of the most giant creatures to ever walk the planet,” says Ken Lacovara of Drexel University, Lamanna’s colleague and lead author of the team’s findings published in Scientific Reports, an open-access journal from the publishers of Nature. The next most complete massive titanosaur, Futalognkosaurus, is only about 27 percent complete. “In a lot of ways, titanosaurs are the final frontier in our understanding of dinosaur evolution,” says Lamanna. “They’re the last major group for which we don’t have a good idea of how the species are related to each other.” Going SouthLamanna and Lacovara have been chasing dinosaurs together for more than a decade— first in Egypt (where they unearthed Paralititan, a much less complete giant titanosaur), then China, and, most recently, in Patagonia. Add in Lamanna’s trips to the Australian Outback and Antarctica, and the pair has largely been zeroing in on the southern end of the world for a reason: Dinosaurs in the Southern Hemisphere are far less known than their more famous counterparts in North America, Europe, and Asia. The short explanation for this is simply that not as many people have searched for dinosaurs in that part of the world, or for as long. The remoteness and hostility of the environments also plays a big role. “Digging for dinosaurs in Antarctica, or even in Patagonia, is like getting on a spaceship and going to another planet, because you’re uncovering entire worlds of animals and plants that nobody knew existed,” says Lamanna. “I really want to know what was living in the southern part of the world at the end of the Age of Dinosaurs. I think the chances of finding something radically different, radically new, and of extraordinary scientific significance are unusually good in those places.”

He can trace his appetite for such adventure back to a March 1987 issue of Discover magazine still tucked away on a bookshelf in his office. What caught his 11-year-old eye? A black-and-white illustration of Carnotaurus, “an evil-looking carnivore from Patagonia” discovered only three years before. The caption informed the budding paleontologist that the odd-looking beast, whose name translates to “meat-eating bull,” played the same predatory role as T. rex in the north, and may have shared an ancestor (scientists now know that, despite their similar appearance, these two are only distantly related). “Dreadnoughtus means ‘fearer of nothing.’ When you’re a behemoth the size of a whale—and you’ve got a brain the size of an apple—it’s probably just about impossible to feel any fear.”

- MATT LAMANNA, CARNEGIE MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY DINOSAUR HUNTER“When I was 11, I think my interest in Carnotaurus could be summed up as something like ‘wow, there are all these really cool, new, and weird dinosaurs out there that I know nothing about,’” Lamanna says. “But as my knowledge of Carnotaurus and other southern dinosaurs grew, my interest in them matured, so to speak. I got interested in their evolution—how they were related, or not, to each other and to dinosaurs in the northern continents, and what that might tell us about the shape of the world during the Age of Dinosaurs.” Two National Geographic articles—one, in 1996, featuring African dinosaurs, and the other highlighting Patagonian dinosaurs a year later—set him on the path he continues to follow. “At the same time T. rex and Triceratops were stomping around North America, equally bizarre, equally awesome, equally spectacular dinosaurs with very little evolutionary connection to Northern Hemisphere dinosaurs were ruling the day in the Southern Hemisphere,” Lamanna says. “When I realized this, it was incredible. And it continues to shape me to this day.” One Big FindFast forward to February 2005, the first of four field seasons—four to eight weeks each— spent digging for Dreadnoughtus. Patagonia is a known fossil hotspot, but most of the big finds have hailed from the northern end of the region. So the team chose to head as far south as possible, to a set of remote, rocky badlands the size of Connecticut containing the Cerro Fortaleza Formation. With the beautiful Andes mountains stretching as far as the eye could see in the background, beneath the team’s feet were ridge after ridge of potentially fossil-bearing rocks from the Late Cretaceous. “It’s the kind of landscape that makes a paleontologist drool,” recalls Lamanna. On the very first day, Lacovara spotted a small patch of bones on the surface and recorded the location with his GPS. He did this 10 more times, then took a break to set up camp. “We returned a few hours later and began excavating at the first location,” Lacovara recounts. “The first bone we uncovered was a giant femur [thigh bone] that’s taller than me.” Having unearthed an even bigger femur the previous year—one that turned out to be an isolated find—he didn’t think too much of it. Until the team found the two shinbones beneath it, just where they should be. “By the end of the day, we had exposed about 10 bones at the surface. Many of the largest dinosaurs are known by fewer than 10 bones, so we knew we had something special.” What’s more, notes Lamanna, the huge shinbones were connected to the ankle. Sounds obvious enough, but as it turns out, locating and identifying massive dinosaurs isn’t as easy as one might imagine. While these giant animals left giant fossils, it’s extremely rare to unearth a nearly complete skeleton; smaller dinosaurs tend to be fossilized all in one spot, but the lumbering giants don’t. And as the team quickly learned, digging up supermassive sauropods is an awful lot of backbreaking work, done almost exclusively with hand tools. “I spent a total of about a year living in a tent next to this dinosaur,” Lacovara says. “You have to be really motivated and well equipped for the job.” He compares the commitment of studying giant sauropods—from discovery to the hailed public announcement and everything in between, including driving a U-Haul truck loaded with priceless fossils from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh by way of the turnpike—to taking out a mortgage. “It takes a long time and it’s a huge investment,” he says. “Not all the work is academic. I had to be a carpenter, truck driver, and negotiator, too,” the latter a reference to working with government officials in Argentina to get a shipping container full of Dreadnoughtus bones out of the country and safely to his lab. Size Does MatterOn that fateful day roughly 77 million years ago, it seems that the two Dreadnoughtus individuals were simply at the wrong place at the wrong time. Lacovara, a geologist by training, believes that after they died—or as they died—they were submerged by a flooding river, turning the ground beneath their feet into a soupy mix of sand, mud, and water. “They likely sunk quickly and deeply—which, lucky for us, accounts for their completeness.”

“As we were working, it was quite the thrill—for visitors and for us—to bring out say a rib and let a child hold a piece of a dinosaur that at that time didn’t even have a name yet,” says Russell Christoforetti, a skilled PaleoLab volunteer who clocked more than 3,000 hours preparing Dreadnoughtus. All the while, Lacovara searched for not only a fitting but memorable name that would do the beast justice. During a big snowstorm two winters ago, he sat on his couch at home and amassed a list of 30 possibilities. He hung the handwritten list on the refrigerator and for two years, every time someone stopped at the house, he’d ask them to respond to the list. Dreadnoughtus— inspired by an armored battleship, which like Lacovara’s dinosaur had nothing to fear—was “the runaway winner,” he says. “It was my pick immediately,” says Lamanna. “We thought it was high time a plant-eating dinosaur got a badass name.” It’s a dinosaur, Lamanna and Lacovara believe, that has a lot to teach them, and the world, about titanosaurs. “There are so many fundamental things we don’t know about them,” says Lacovara, such as the arrangement of their muscles and ligaments and how they moved. That’s why the researchers performed laser scans of each and every bone—itself a massive task, considering their size—and published the resulting 3D models online, marking the first time models have been released publicly for a brand-new dinosaur species. And that’s just the beginning. Ten additional studies and six Ph.D. dissertations are currently in the works, all focused on learning even more about the secret lives of super-massive dinosaurs like Dreadnoughtus. “It’s amazing to think there’s a possibility that some kid is going to open up a magazine or be messing around online and come across Dreadnoughtus or Anzu [Anzu wyliei, nicknamed the ‘Chicken from Hell,’ a new species of oviraptorosaur named recently by Lamanna and colleagues] and form an entire career around it, the way I formed my career on Carnotaurus,” says Lamanna. “Or maybe that kid goes on to do other things, scientifically speaking, and an interest in paleontology is just the start. As paleontologists, we’re not out there curing cancer—but we just might inspire the person who eventually does.”

|

|||||||||

Changing the Equation · To Have and to Hold · Art Responding to Life · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Tim Pearce · Artistic License: An American Treasure in the Making · About Town: Ask a Scientist · Science & Nature: Painting the Parade of Life · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |