|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bright, bold, and beautiful, the artwork of Corita Kent reflects the struggles of a generation and the soulfulness of the unlikeliest of Pop-art heroes. Consider the plump tomato. Cup it in your hand—it sits like it was meant to be there. Peel its thin skin to divulge the juicy flesh contained within. Then discover one of the most visceral culinary pleasures: Squish—not squash—that tomato into a pot of soup. Juice and pulp and slippery seeds explode through your fingers with a satisfying pop. The aroma is heavenly. Life is good.

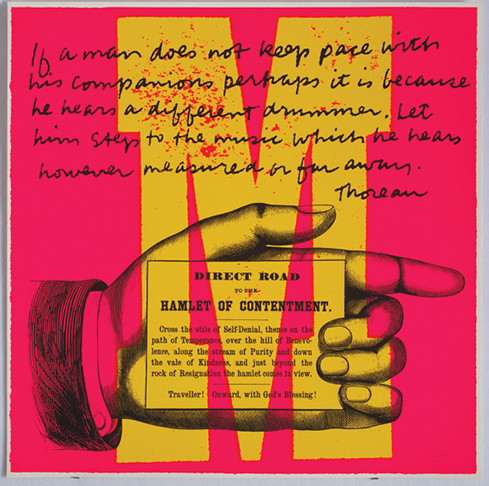

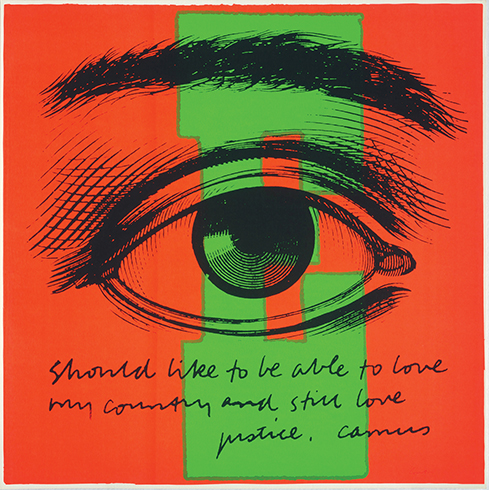

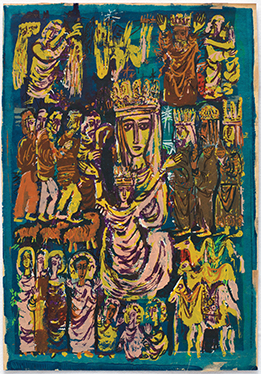

The stuff of life—culture, religion, justice, found objects, what she saw through the finder of her 35mm camera—was Corita Kent’s tomato. As an artist, a teacher, and a member of the Immaculate Heart of Mary order in Los Angeles, she held that tomato in her hand and squeezed for all it was worth. Delight and purpose permeates Kent’s work—whether it’s the 12 sly Eames chairs in at cana of galilee, or the way she turns Del Monte’s advertisement for tomatoes into an unconventional reflection on the Blessed Mother Mary in her 1964 serigraph, the juiciest tomato of all. “Whether you are an artist or not, a life is a complex stew of influences and ideas and feelings and conditions. And Corita exemplifies that,” says Ian Berry, director of the Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College and co-curator of Someday is Now: The Art of Corita Kent. The exhibition, which opens at The Andy Warhol Museum on January 31, 2015, surveys 30 years of Kent’s work. Berry describes the artist, who died in 1986, as a genius designer and a devout person who had great faith in her fellow humans. “She was also a very fierce person. She was uneasy about things that were happening in the world, and she wanted to speak out about them,” he says. “She wanted more from the world. You see that in her prints. They ask a lot of philosophical questions. A lot of them even end in question marks—questions to get us to think about how we’re living our lives, how we’re choosing to live out our days.”

Raised in Hollywood, California, Kent, the fifth of six children, was educated in Catholic schools and entered the convent at age 18. She graduated from Immaculate Heart College in 1941 and would go on to run the Los Angeles school’s esteemed art department until 1968. Early on, Kent landed on printmaking and its potential for mass communication as her medium. Her work combined bright swaths of color juxtaposed with graphic typography or blocks of text scrawled in her own handwriting. Her earliest works were largely iconographic, borrowing phrases and depicted images from the Bible. “A true appreciation of art involves a study of life, which requires working with words and ideas.”

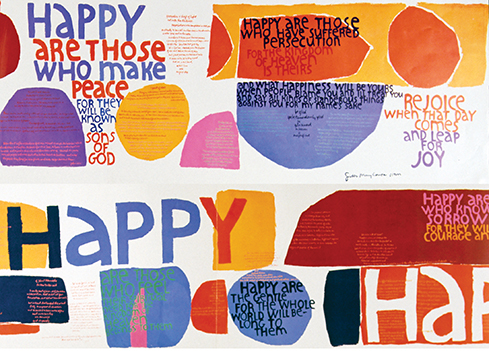

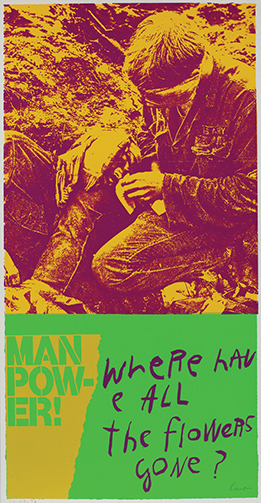

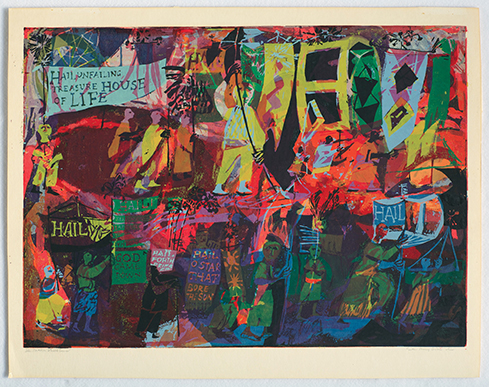

- CORITA KENTBy the 1960s, Kent was thoroughly in command of her own voice, style, and message. “Art does not come from thinking but from responding,” she would say. And respond she did, appropriating popular culture and catchy advertising to explore her faith and politics amid changes to religious life in the wake of Vatican II as well as the widening social consciousness brought about by the civil rights and antiwar movements. When Andy Warhol exhibited his Campbell’s Soup Cans in 1962 at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles—his first solo Pop art show—Kent visited, her sweater-set and wool-skirted students in tow. Her reaction was animated. “Coming home you saw everything like Andy Warhol,” she said later. Roughly contemporaries (Kent was 10 years older and died a year earlier than Warhol), both were masters of graphic design and knew how to use bright, bold color to great effect. Likewise, understanding the power of widespread circulation of their images, they each chose silkscreen as their medium. Each explored pop culture, although to different purpose. “That process of seeing something in the everyday world, and turning it and adding to it to make it complex and individual is one way of understanding what Pop art is,” says Berry. “It’s certainly a way that Corita worked, right alongside all of the artists that were creating this new image art—a new image that included a Campbell’s soup can, or an American flag, and, in Corita’s case, a logo from Sunkist orange juice.” A Voice of a GenerationThe 1960s brought widespread recognition of Kent’s work. She was engaged to create high-impact commissions, such as the IBM Building windows in New York for Christmas (Peace on Earth, 1965). For the Vatican Pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York City, she designed a 40-foot banner. Titled Beatitudes Wall, it’s dominated by the graphic repetition of the word “Happy” (as in “Happy are those who make peace for they will be known as sons of God.”) The Eight Beatitudes from Christ’s Sermon on the Mount are interspersed with organicallyshaped bursts of color filled with the words of John F. Kennedy and Pope John XXIII.

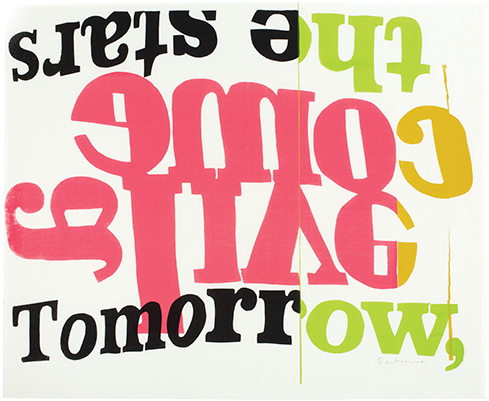

With her populist notion of art, Kent made sure her work was affordable. She allowed her designs to live on greeting cards, T-shirts, book jackets, and posters. Words were important to her—she loved to quote e.e. cummings, Gertrude Stein, Jefferson Airplane, and the Bible. She encouraged her art students at Immaculate Heart to minor in English. “A true appreciation of art involves a study of life, which requires working with words and ideas,” she said. She also loved words purely for how they looked. “I suppose from seeing posters and reproductions of posters, I got the idea of there being different possibilities of using letter forms,” she told Bernard Galm in a 1977 interview for UCLA’s Oral History Program. “I always think of the letter forms as much as objects as people or flowers or other subject matter.”

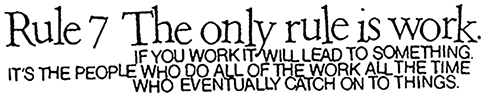

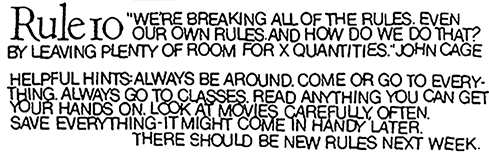

She did not hold art precious, although she clearly held it to high standards. There was a Balinese saying in her classroom studio: “We have no art. We do everything as well as we can.” Her focus was on the doing, on the physical connection of hand to tool, on remembering to see, to look long enough to understand more deeply. As head of the Immaculate Heart College art department, she posted a set of 10 rules in beautifully uneven lines of letters— rules that still get passed around art classes today.

While Rule 7 captures the central tenet of Corita’s philosophy, Rule 10 is where you see her smile and wink with a quote from John Cage:

Kent’s rules will be displayed at The Warhol within the exhibition’s interactive gallery space where visitors can tackle some of her art assignments, says Tresa Varner, the museum’s curator of education and interpretation. The Warhol’s Power Up program—an after-school and summertime series for African-American teenage girls—was named, in part, after a Kent print, and it has long been inspired by her practice. “The program is about empowerment through the arts,” explains Varner. “Corita was really mixing the everyday, but not just at the surface, commercial, consumer-cultural level; she was also digging into our faith as a nation and our politics and our views of civil rights.”

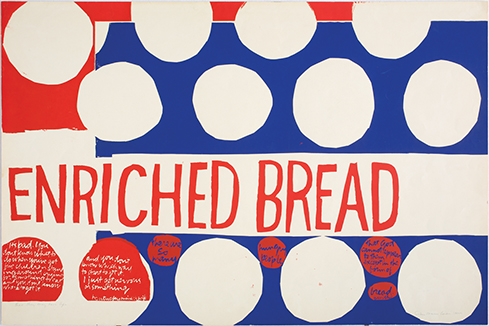

The museum’s Power Up participants get a chance to do the same, as they give voice to their own social concerns, Varner says. The young women learn art-making skills as a way to communicate important subjects around women’s health issues and rights. They’ve partnered with Planned Parenthood, for example, to design materials around misconceptions about pregnancy, HIV, and AIDs. A Timeless MessageMost of Kent’s own work was done in furious, threeweek bouts of printmaking each August when she was free from teaching responsibilities. She would always take batches of the new prints home to show her mother. “I think she always half-loved them because her daughter had done them, so she was much kindlier to them than the conservative part of the family,” she told Galm. The last time Kent brought a set to her, her mother commented, “Don’t you think you’ve gone a little too far this time?” Still, out of the set, Kent’s mother liked Wonderbread, which Kent found amusing: “There were just 12 circular images, different colors. And that was one of her favorites, which I thought was quite far out, as they say, for her, who thought I had gone a little far that year.”

In the December 25, 1967, issue of Newsweek, Kent was featured on the cover with the title: The Nun: Going Modern. Ironically, she left the order in 1968, moving to Boston’s Back Bay area to focus on her artwork. It was a foreshadowing of what was to come with the entire order. They’d been in the crosshairs of conservative Los Angeles Cardinal James McIntyre for their liberal ways and joyful adoption of the Vatican II resolutions. In 1970, more than 300 of them removed themselves from the purview of the Catholic Church and formed a lay community. Many contemporary artists have found inspiration in Kent’s work. Political artist Andrea Bowers recently wrote that one of Kent’s silkscreens hangs prominently in her bedroom. “So every morning I wake up and read, across the room, Hip Deep Ornery, with the ‘ornery’ written backwards. Somehow it feels like a description of my personality, and I am always grateful for that backwards ornery; somehow it has more grace that way,” she writes. “Just about every aspect of Corita’s work continues to influence my own practice. I am constantly in awe of her aesthetic decisions.”

Kent’s contributions, says Berry, form a critical piece of art history. “Corita is a new discovery to our current generation,” he says. “She’s right in there with a group of innovative artists who were bringing the everyday world into the realm of museum art in a way that hadn’t been done before.” “Art does not come from thinking but from responding.”

- CORITA KENTThe way she could manipulate type, for example, is still revered by graphic designers all over the world.

“She didn’t purely invent for formal pleasures, although you can see a great joy and pleasure from her formal play with design. But she was always in the service of the message,” he notes. “And these carefully chosen quotes tease out some of the big issues of the ‘60s: race, gender, war, consumption, certainly about faith in all of its definitions. She was a real reflection of her time.”

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Changing the Equation · To Have and to Hold · Living Large · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Tim Pearce · Artistic License: An American Treasure in the Making · About Town: Ask a Scientist · Science & Nature: Painting the Parade of Life · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |