Winter 2014

Winter 2014|

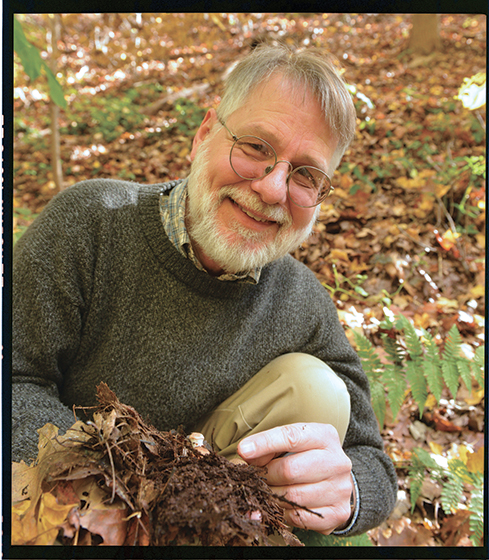

Tim Pearce

On a beautiful fall day, Tim Pearce walks through Schenley Park and barely notices the spectacular sights around him. His gaze is diverted downward, to the “leaf litter” beneath and beside a large fallen tree—nirvana to a snail guy like Pearce. He grabs a handful of wet leaves caked in dirt and gets lost in the moment. “Cool—look at these guys!” he exclaims, as he picks apart its contents. As assistant curator and head of mollusks at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pearce spends a lot of time sifting through dirty piles that he and others collect, much of it from Pennsylvania’s 67 counties. The affable nature lover—with master’s degrees in paleontology and biology from, respectively, the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Michigan, where he also earned his doctorate—is still, at his core, that 8-year-old kid in rainy Seattle, Washington, marveling at all the snails and slugs that were his neighbors. The mollusk collection he now manages, which numbers about 3 million specimens, boasts more land and freshwater snails from Pennsylvania and its adjacent states than all other U.S. museums combined. Those numbers continue to grow, as Pearce and a small band of volunteers and grantfunded assistants work on a definitive census of the state’s land snails. One recent grant, funded by the state’s Wild Resources Conservation Program, required Pearce to identify the snail species most susceptible to climate change. He determined they were those that live in the state’s highest elevations; they’ll have nowhere left to go should our climate keep getting warmer, he notes. “If I say ‘think of an animal,’ most people think of a mammal. We need to think more about and learn from mollusks, our second largest category of animals on the planet.” How can you find such tiny creatures?Because I’m a scientist! That’s a quote from the movie Ghostbusters, by the way. What we do, simply, is bring back bags of soil and leaves, dry them, then filter off the larger pieces until we find specimens. When did your interest in mollusks begin?I’ve been interested in nature my whole life. My mom tells me that when I was 3 years old I collected a cottage-cheesecarton full of snails and took it with me to a doctor’s visit. What classifies as a mollusk, and why is it important to study and collect them?Mollusks are snails, mussels, scallops, oysters, squid, slugs. Most have shells, and some have shells on the inside. If you take all the multi-cellular animals in the world, the arthropods— the bugs, insects, and crustaceans such as crabs— make up 75 percent of all animal life. But mollusks are the second largest phylum, or group. Land snails and slugs are food sources for other animals, and freshwater mussels filter waste from rivers and lakes. So they’re important to their ecosystems in that they serve an important purpose. And because museums have specimens of mollusks preserved over centuries, we can tell what once was, and then infer what could influence their extinction. A great deal of conservation work is based on museum collections like ours. How far along are you in your census of Pennsylvania land snails?I’ve gridded the state off into 6-mile squares, and my goal is to get a leaf-litter sample from every one of these squares. About 50 percent of my grid squares have been collected after 12 years. Eventually, if I start seeing patterns I’ll believe them. Right now, I don’t believe any patterns I see because snails in the state are still under-sampled. Do you have historic data to compare the new samples to?We do have important historic data because we’ve got a museum full of specimens, and a lot are from Pennsylvania; that’s the largest part of our collection. The entire collection has moved to a new space. How did that come about?We received a large grant from the National Science Foundation to help us address two main problems: The collection wasn’t accessible, and the specimens were in perilous conditions. The beautiful wooden cabinets that stored them were about 100 years old and still giving off acid vapors. Given enough time they would have turned the shells into a pile of powder. We’ve moved everything to these archival, metal cabinets in our new basement space. And the collection is now about 85 percent digitized, which makes it easier to search. You give regular tours of the collection to visitors (every second Saturday). Do you enjoy that?I love sharing my enthusiasm for mollusks with the public, because most people don’t know anything about them. And visitors who come into the collections are just amazed. I feel very strongly about it. We as a museum need to demonstrate to the public that we’ve got these fantastic, irreplaceable collections. People are using them to do valuable research, and it’s important for visitors to see that.

|

Changing the Equation · To Have and to Hold · Art Responding to Life · Living Large · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Artistic License: An American Treasure in the Making · About Town: Ask a Scientist · Science & Nature: Painting the Parade of Life · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |