|

||||||||||||||||

|

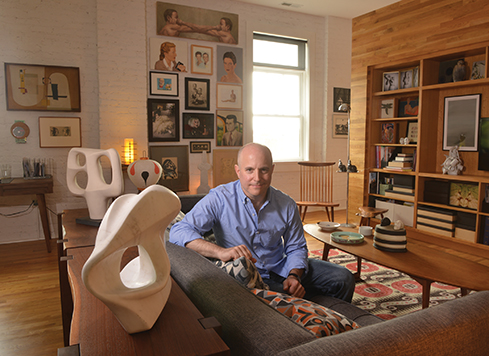

Duane Michals with work from Collector, which runs through March 2, 2015. Photo: Bryan Conley |

To Have and to Hold

A glimpse into photographer Duane Michals’ personal art collection reveals fascinating connections to his own art-making. What motivates other art lovers to collect? Regional collectors reveal their own labors of love. Duane Michals was strolling along the popular Rue de Seine in Paris in 1964 when he happened by a print in the window of an art gallery. Staring at the image of a hand with a sleeping woman’s face coming out of the wrist, he realized it was by René Magritte, one of his favorite artists.

The next year, he was even more thrilled when Magritte, the great surrealist, agreed to let Michals photograph him at his home in Brussels. “I had the run of his house for a week,” says Michals. “It was the most generous event of my life.” Michals’ book, A Visit with Magritte, is part of the enormous volume of work he produced over the next six decades. Best known for his photographic sequences and the text he handwrote in their margins, at the time controversial practices, Michals’ artwork earned him his share of detractors but also a reputation as an innovative storyteller. As his international fame as a photographer grew, so did his personal art collection that lined the walls of his Manhattan brownstone. The intimate relationship between that collection and Michals’ own art-making is now in the spotlight at Carnegie Museum of Art. Running concurrent to Storyteller: The Photographs of Duane Michals, a definitive retrospective of the artist’s work, is Duane Michals: Collector, a group of 49 works that Michals bought over his lifetime and recently donated to the museum. (The retrospective is on view through February 16, 2015, and Collector closes two weeks later.) “It’s a oncein- a-lifetime opportunity to see how Duane’s artwork is related to the things he lived with for a long time,” says Amanda Zehnder, associate curator of fine arts. “His collection is very eclectic, but it makes sense when you see his work.”

Though the 82-year-old McKeesport native made his mark using a camera lens, his collection includes work as diverse as a 1799 etching by Francisco de Goya, a 1999 painting by Mark Tansey, and a trio of early photographs by André Kertész. Key themes, says Zehnder, reflect ideas Michals has spent a career exploring—humor, imagination, and no surprise, the interplay of image and text. In some ways, Michals says, donating his collection to Carnegie Museum of Art completes a circle. “I’m looney for Pittsburgh,” he says. “It was very natural for me to give it to the museum, which was so important to me as a kid.” “Every time I look at the work I own, it reinforces the aesthetic pleasure spot in my brain.”

- DUANE MICHALSThe artist who grew up in a workingclass household without art—“we could barely afford a calendar”—discovered its magic within the Museum of Art’s galleries, a debt of gratitude he repaid with an unexpected and extraordinary gift. “It’s very rare that an artist you support turns around and is this generous to a museum,” says Lynn Zelevansky, The Henry J. Heinz II Director of Carnegie Museum of Art. For collectors like Michals, art isn’t an investment. It’s about the sheer joy of living with something that touches their souls, and inspires them to seek out the next treasure. Growing the number of collectors regionally is important not only to the museum but to Pittsburgh, Zelevansky asserts. “Pittsburgh needs collectors to grow in the arts,” she says. “They’re crucial. People who get hooked on art are the people who are looking for meaning beyond the consumption of things.”

And so it is with Michals and three regional collectors—David Werner, Chris King, and Evan Mirapaul—each of whom find meaning in art in different ways. Michals, for instance, buys an eclectic mix of art from all time periods to nourish his creative spirit. “Every time I look at the work I own, it reinforces the aesthetic pleasure spot in my brain,” he says.

Sue and David WernerTwenty-five years ago, David Werner began collecting American 19thcentury paintings, but quickly felt frustrated at the New York auctions. Whenever the State College ophthalmologist bid on a significant work, he watched it slip out of his grasp to higher bidders. Then Joe Keiffer, a New York artist, explained to him that too many collectors were chasing too few American paintings, so the prices were astronomical. Even if he got lucky, building such a collection wouldn’t stand out among the crowd. Keiffer advised Werner to go in a new direction and collect a different kind of art: Scandinavian. “Scandinavian?” Werner exclaimed in disbelief. Why in the world would he collect Scandinavian art? Because, Keiffer said, there was great work there at more reasonable prices, and with far fewer collectors chasing it. So Werner boarded a plane to Copenhagen, bought a handful of beautiful Danish landscape paintings, and never looked back. So taken by the work, he expanded his newfound passion to Swedish, Norwegian, and Finnish fine and decorative arts. “It was a Domino effect,” he says. “Each one of these countries is an independent nation with their own histories of conflict and compromise. Each one has a personality, but there is a certain degree of flow between them.” The airy State College home he shares with his wife, Sue, is filled with dozens of Scandinavian paintings, ceramics, sculptures, and rugs—one of the most extensive Scandinavian collections in the country. “It’s been an opportunity to do something unique in the art world that I also really enjoy,” says Werner, a Museum of Art board member and vice chair of its collections committee. For Werner, buying and living with art is both an aesthetic and academic adventure. He and Sue take art and bicycling vacations in Europe, where he spends entire days visiting museums. During a visit to a museum in Stockholm, he was captivated by a Gustaf Fjaestad painting of a landscape dominated by hoarfrost, a crystallized frost that forms on trees. When one came up for auction 18 months ago he pounced, and the prized possession now hangs in the couple’s bedroom. One of his greatest finds occurred just five miles from the couple’s home, at an estate sale. Werner bought a Viking-style chair so covered in grime and cobwebs that Sue gasped when he brought it home, insisting it be kept in the basement. “It’s filthy and it’s going to scare the grandchildren,” he recalls her telling him. He spent hours cleaning it, eventually revealing beautiful inlay carvings. It wasn’t until the couple was in the Musée d’Orsay museum in Paris that they understood what they had. As Werner walked by a glass display case, he stopped in his tracks, declaring, “That’s our chair.” Except the museum chair was half the size. He realized then that the discarded chair he had picked up for a song was crafted by Lars Kinsarvik, the Norwegian woodcarver and designer, for the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris. He loved tracing the chair’s long history, which taps Norway’s Viking past and represents national romanticism just prior to the country’s independence in 1905. “A country’s art is often an expression of the country’s soul,” he says, noting that he and Sue loaned the chair, an important example of Norwegian Art Nouveau, to the Museum of Art for its traveling show Inventing the Modern World: Decorative Arts at the World’s Fairs, 1851–1939. Sue, who has veto power over purchases but rarely exercises it, says, “It’s more than his hobby. At times his passion can become an obsession—but a good one.”

Chris KingThe wood wall above Chris King’s bed was empty, and the contemporary art lover was just waiting to find the right work for the intimate space inside his sleek Garfield apartment. A friend showed him a self-portrait he had just bought from Pittsburgh-based painter Fabrizio Gerbino. In it, a nondescript object obscures the artist’s face. That was it, Chris thought—the perfect piece. Even better, Gerbino was a friend whose abstract industrial paintings King had bought in the past. He called the artist and learned he had a similar painting in his studio in nearby Stowe Township. “It’s interesting and mysterious,” King says. Whenever he can, the business consultant enjoys buying art directly from artists who are based in Pittsburgh and Chicago, cities the Beaver County native now calls home. Immersed in Pittsburgh’s art scene, he owns works by many regionally based artists with national reputations, including Diane Samuels, Ed Eberle, David Stanger, Vanessa German, and Gerbino. King is drawn to their unflinching passion. “I think a lot of artists are such interesting people— to devote yourself to your art knowing that it’s a very rough road.” “ I think a lot of artists are such interesting people—to devote yourself to your art knowing that it’s a very rough road.”

- CHRIS KINGHis 1,400-square-foot apartment looks much like a contemporary art gallery, with paintings lining its clean white walls and abstract sculptures atop modern wooden furniture. For King, collecting is a way to feed his love of design and surround himself with beautiful objects. A wonderful benefit, he says, is meeting artists who share the back stories of their work. One wall in his living room is filled, floor-to-ceiling, with portraits, including a work by Stanger that’s a mirror image of two men punching each other in the face. “He transferred paint from one panel to the next,” notes King, explaining Stanger’s process for creating the reflective image. “It took 10 to 15 steps.” Above his desk is the artist’s sketch that shows where the fist should land on the face. In another corner rests a sculpture of an African-American queen, her face an iron, by Homewood-based artist Vanessa German. In an interesting personal twist, German, who uses recycled materials for her sculptures, bought objects during an estate sale held for King’s aunt and uncle. He recognized some of his relatives’ castoffs in her later work. So it’s fitting that he placed her sculpture on an antique wooden table once owned by his aunt and uncle. “I love it,” says King of the work German calls a contemporary power figure. “It’s iconic.” Evan Mirapaul

“They say, ‘I could have bought a Rembrandt in 1962 for 16 cents,’” he says playfully. “Or, ‘the dealer didn’t know what he had.’” But inside his 19th-century Troy Hill home filled with 21st-century photographs, Mirapaul doesn’t spend his days regretting what he didn’t buy. “I’m a contrarian on that,” he notes. “I’m more thrilled thinking about what I didn’t buy than what I could have bought. I know I would have been bored; or it wouldn’t hold its value; or it was overpriced.” He does confess to having one regret: He wished he’d purchased a Composite by Ray K. Metzker (images stemming from the artist’s insight that a single work could be created from an entire roll of film) that he passed on in 1993. So he went so far as to track down a similar one almost a decade later. “I paid probably three times as much,” he says. Metzker, a renowned modernist photographer who passed away this past October, is now the most represented artist in Mirapaul’s collection of photographs and drawings. Hanging prominently in his living room is a Metzker Composite made of dozens of photos of tiny human figures combined in an enigmatic pattern. Many of the works in Mirapaul’s collection feature text versus recognizable images. Among some of the most interesting: typewriter drawings by Allyson Strafella, a lithograph of a facsimile Walmart receipt by Joe Lupo, and an Erica Baum photograph titled Pause, which features the word as part of a scan of a player piano roll from the early 20th century. “People call me a photo collector,” he says. “I consider myself a works-on-paper collector. I’m interested in text. I like things where there is some kind of language being used to which there is no possible access. It’s a system but you can’t read it. It’s more of a question than an answer.” The former violinist for the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (“a recovering professional musician,” he quips) Mirapaul has collected thousands of photographs of people holding violins. Among them: an Irving Penn portrait of famed violinist Jascha Heifetz, a performing Jack Benny held aloft by U.S. troops in Nuremberg Stadium, and vintage images of women posing with their instrument, often in restrictive period clothing. “The violin transcends every border, nationality, social status, and gender,” says Mirapaul, a Pittsburgh transplant. “For example, some people get photographed with a violin to show how ‘country’ they are, while others get photographed with a violin to show how wealthy they are.” “I like things where there is some kind of language being used to which there is no possible access. It’s a system but you can’t read it. It’s more of a question than an answer.”

- EVAN MIRAPAULHe began collecting images in 1989 after he and his brother, Matthew, happened upon the exhibition On the Art of Fixing a Shadow: 150 Years of Photography at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., which expanded their idea of what a photograph could be, and introduced them to cutting-edge work by artists like Duane Michals. Then, upon traveling to San Francisco and visiting the city’s many photography galleries, the pair discovered that owning original art was within their price range. (Today his collection is so extensive he loaned a Duane Michals print to the Museum of Art for inclusion in the current exhibition Storyteller.) When Mirapaul returned to Pittsburgh in 2010 after more than a decade in Manhattan, he opted to pay it forward by founding the PGH Photo Fair in 2012, an annual event that brings internationally known photography dealers to the city. “Many people in Pittsburgh view art as institutional, not personal,” he says. “They just haven’t had the experience my brother and I had of going to a gallery and saying, ‘This is not that expensive and I really like it.’ It can be transformative.”

|

|||||||||||||||

Changing the Equation · Art Responding to Life · Living Large · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Tim Pearce · Artistic License: An American Treasure in the Making · About Town: Ask a Scientist · Science & Nature: Painting the Parade of Life · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |