|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Small Prints, Big Artists

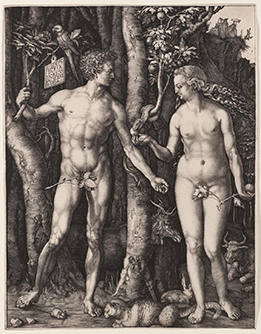

Printmaking was a game changer. A new look at its history as an art form highlights works by some of the best-known artists of the Renaissance and beyond. For four consecutive days last March, curator Linda Batis sat in the print storage room at Carnegie Museum of Art, sorting through a collection she knew well but hadn’t seen in years. The room, lit softly to preserve the aging paper, houses the museum’s collection of 8,088 prints—the largest in oversized drawers and the smallest in four-inch-high boxes on shelves. Chronologically, Batis looked through a group of works known as “old master prints,” which date between 1470 and 1750 and come from Western Europe. It wasn’t long before she pulled out a particularly brilliant print, an impression of Adam and Eve by German printmaker Albrecht Dürer.

Made in 1504 from a copper engraving, the small and sophisticated print is considered a masterwork by one of the earliest European printmakers. In it, the idealized pair stands gazing toward each other in nearly symmetrical postures. Eve holds a fig passed to her from the serpent’s mouth and Adam clutches a knotted branch from the Tree of Life. Textures of tree bark, snakeskin, and human flesh are unmistakable. “Momentarily, it takes your breath away,” says Batis. In fact, the Museum of Art’s impression of Adam and Eve is one of the finest examples in the world. Now it’s among more than 200 works selected by Batis for Small Prints, Big Artists: Masterpieces from the Renaissance to Baroque, the first exhibition at the museum comprised exclusively of old master prints. On view now through September 15 in the Heinz Galleries, the show features a cross section of work that not only tells the history of printmaking as an art form, but also includes dedicated sections on two of the greatest printmakers of the time: Albrecht Dürer and Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn. Though Batis is not based in Pittsburgh—today she lives and works in Greece— she spent 12 years as an associate curator in the Museum of Art’s fine arts department specializing in old master prints. She knows this collection well, perhaps better than anyone, says Louise Lippincott, curator of fine arts. So when Lippincott hatched the idea for the show, she contacted Batis and invited her to guest curate. Over a year, Batis made several weeks-long trips to Pittsburgh to dig in and revisit the works in person. “It’s like getting to see old friends,” she says. Sifting through the collection last March, Batis kept a running tally in her mind. Like a judge who scores a gymnastic event for both artistic merit and technical skill, she vouched for the beauty of the image and then, with her nose close to the page, set about ranking each impression for technical quality. Here, it’s important to understand a few distinct terms.

Each item in the collection is an “original,” which is to say an ink impression taken directly from the artist’s woodcut or metal plate. Around the world there may be dozens of surviving impressions of each work. Though at first they may appear to be duplicates, not all impressions are created equally. For instance, the first few impressions taken from a plate have crisper lines. Some are made on better paper. Others have richer ink. The image on the plate or woodcut may be beautiful, but for any number of reasons, the impression may fall flat.

The MastersThe earliest prints in the exhibition, dating to 1470, are pages from a “block book.” In this primitive publishing style, “the text and pictures were printed from the same block of wood, and then the print was hand colored after that,” Batis explains. The imagery appears almost cartoonlike and marks a rare example of color in the collection. From there the show moves through time, artist, and region to illustrate the major trends in Western printmaking. There are the Little Masters of Germany and their tiny prints the size of postage stamps; Mannerism and the strangely elongated figures of Hendrick Goltzius; and 18th-century Italian printmaking and the large-scale etchings of Rome by Giovanni Battista Piranesi. But the greatest highlights of Small Prints, Big Artists come at the beginning of the exhibition, and again at the end. Bookending the show are substantial collections of works by Dürer and Rembrandt. Separated by more than 100 years, these two productive artists employed vastly different styles. “It’s partly a question of artistic approach, and partly a question of how much the technique of printmaking had changed from Dürer’s time to Rembrandt’s time,” says Batis. “We’ll show how printmaking developed from being a really primitive medium into something incredibly sophisticated.”

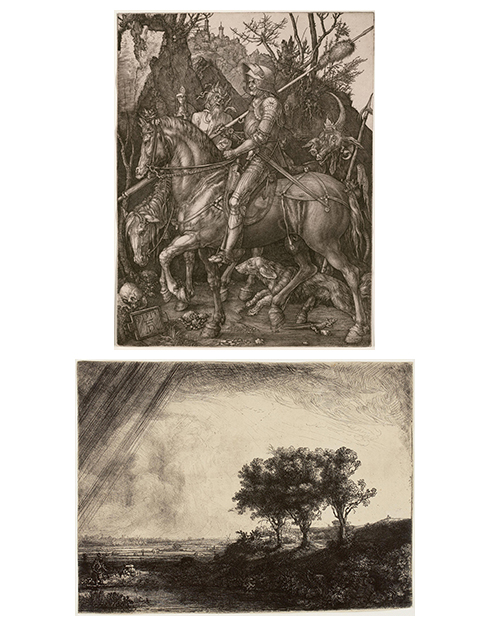

- Curator Linda BatisIn late 15th-century Germany, Dürer worked primarily in woodcut, quickly surpassing the established rudimentary craft of block books to create detailed prints of incredible complexity. Woodcut is a relief printing technique in which the non-printed or “white” space is chiseled away, leaving the image at surface level to be washed with ink. Engraving, a similar practice that replaces wood with a copper plate, also became a common technique of Dürer’s. With extreme precision and detailed lines, he compressed vast biblical stories into single pages. These works were widely collected throughout Europe and garnered the artist notable fame at a young age. In addition to Adam and Eve, the exhibition includes fine examples of the three prints widely considered to be Dürer’s most important: Knight, Death, and the Devil (1513), Saint Jerome in His Study (1514), and Melencolia I (1514). “While Dürer was the master of line, Rembrandt was the master of tone,” says Graham Shearing, an art collector in Pittsburgh who owns works by both artists. By the 17th century in the Netherlands, artists had branched away from religious and mythological subjects and begun to create landscapes and scenes from everyday life. The use of woodcut and engraving faded out in favor of etching, a less laborious technique that precluded the need for metalworking skills and more closely mimicked the practice of drawing. Starting with a wax-covered plate, an artist would use a needle like a pencil, stripping away the wax to expose lines of metal. The exposed lines were then dipped in an acid bath, eaten away, and filled with ink to create a print.

Consider Rembrandt’s The Three Trees (1643), his greatest and most striking landscape. The scene is dominated by three trees standing on a small bluff. They are enveloped in sunlight and surrounded by ominous and swirling clouds. Within the shadows are elements of man—a fisherman watching over his line, two lovers in the brush, and a town in the distance obscured by the storm. Created using a combination of engraving, etching, and drypoint (in which sharp needles scratch directly into the metal plate), the print is richly textural and conveys a sense of nature’s dominance over man.

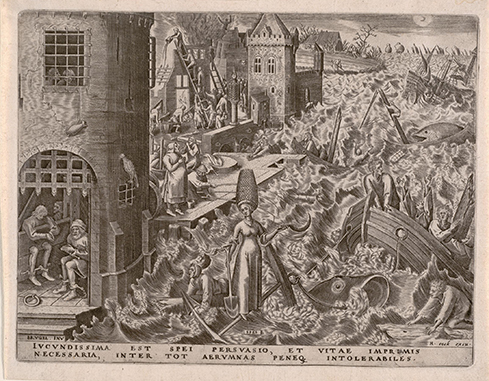

STOP, LOOK, AND LINGERSupplementary materials speckled throughout the galleries illustrate how printmaking enabled art to circulate widely throughout Europe for the first time, gaining new fame for artists and sparking a catalytic effect on communication. In the 16th century, “the majority of Europeans, including the aristocrats, couldn’t read,” says Lippincott. “But they could understand a picture, so these prints became incredibly powerful forms of visual communication.” The work of mid-16th-century Flemish printmaker Pieter Bruegel is a good example. In his allegorical series The Virtues, each of the seven virtues appears as a female figure within a complex scene of grotesque and fantastical subjects. The series is filled with symbols, proverbs, and lessons for living, says Batis. “To us they look weird and bizarre, but to contemporary viewers they would have instantly meant something.” A set of iPads stationed nearby helps visitors decode these hidden symbols. “Like when you see that Nike swoosh and it triggers something in your memory,” Batis notes, “they would have seen the woman with a bird on her head and known that she was Charity.” In this way, Small Prints, Big Artists is an exhibition that asks viewers to linger. “What is kind of difficult about a print is it requires an extraordinary attention to detail,” says Shearing, who has also spent time in the museum’s collection room. To get the very most out of an old master print, he says, “imagine viewing a print in a darkened room using one of those little pen lights. You hold it at a distance and see the entire print, and then you move the pen light onto little individual elements.” Surely a knowledge of history, technique, and the elements of allegory will add interest for any viewer. But for Batis “the most important thing is to look,” she says. For her, the most striking details in the show are textural—the contrast between the metal shield and a young woman’s skin in Dürer’s Coat of Arms with a Skull (1503), and the spare sky in Rembrandt’s The Goldweigher’s Field (1651), which portrays the wet atmosphere of Holland. “These prints have tremendous power as images,” she says. “And that’s the first level on which they should be appreciated.”

|

||||||||||||||||||

Andy Warhol, Revealed · Rockhound · Picture This · Special Section: A Tribute to Our Donors · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Catherine Evans · About Town: A Legacy of Science · Artistic License: Home-field Advantage · Science & Nature: Big Blue · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |