|

||||||||||||

|

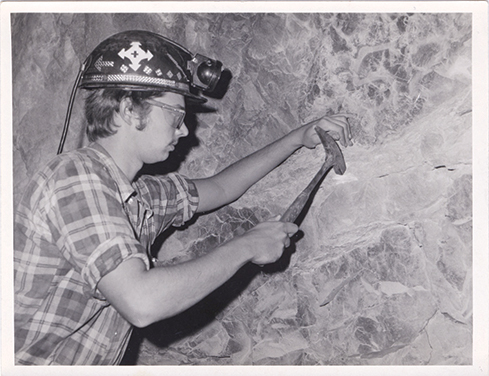

More than 100 of Bryon Brookmyer’s best specimens are on view in Hillman Hall of Minerals and Gems. Front and center is one of the world’s most amazing calcite specimens, unearthed by Brookmyer. Photo: Joshua Franzos |

Rockhound

How Bryon Brookmyer turned his mineral-collecting hobby into a gold mine of Pennsylvania geological history—now an important part of Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s vast collection of underground treasures from the Keystone state. Growing up in the tiny Pennsylvania Dutch town of Blue Ball, Bryon Brookmyer spent nearly every waking hour outside. Like lots of kids, he would scour the fields in search of arrowheads and cool-looking rocks. The rusty yellows and browns of limonite and the golden glitter of pyrite, better known as fool’s gold, always caught his attention. By the early 1960s, Brookmyer got his first bike—and that’s when things took a serious turn. This meant he could pedal to the nearby quarry and hunt around for his favorite golden, pink, and purple rocks, which he would proudly display in canning jars “borrowed” from his mom. One day, he arrived at the quarry to find it overflowing with hundreds of rockhounds, the nickname for members of regional mineral, fossil, and lapidary clubs. So, he did what any enterprising 10 year old would do— he sold those jars for $20 a pop. “I thought I was rich,” recalls the 59-year-old, laughing. But Brookmyer quickly realized he wasn’t interested in the money. Not really—it was all about the rocks. And fortunately for Carnegie Museum of Natural History, not just any rocks, but those which speak to the rich and sometimes colorful geologic history of his home state. That epiphany sent him down a path he’s been following ever since. “I never wanted to become a dealer,” he explains. “I never wanted my hobby to be my job.” In March, Brookmyer’s hobby became Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s windfall, as the avid field collector struck a deal with the museum for his vast collection, making the museum the home of the most complete collection of Pennsylvania minerals, dating back nearly 175 years. “It means a lot that the collection is in a museum in Pennsylvania where people who live here can see it.”

- Bryon Brookmyer

As a young man, Brookmyer always made a clear distinction between his work and his passion. He decided that a job was simply about making a living, but his hobby was about enjoying life. So for years, he punched the clock at Bethlehem Steel, and today he puts in his 40 hours a week at a local water treatment plant near his Mechanicsburg home. “I have no talent for writing, art, or music,” he says, “but I love to get out into nature and see how beautiful it can be.” And in his estimation, nowhere is the beauty of nature more evident than in the “wonderful and diverse” minerals that lay beneath—sometimes pretty deep beneath—the Pennsylvania terrain. 300 VARIETIESRocks are comprised of one or more minerals and can range in size, density, and weight from mountains and boulders to pebbles and specks. Minerals are defined by their specific crystal structures and chemical compositions. An astonishing variety of 300 minerals, including calcite, dolomite, pyrite, and quartz, have taken up residence in the Keystone state, and each reveals a part of Earth’s millennias-old history. Although Brookmyer’s collecting history doesn’t stretch back quite that far, over decades he evolved into a rock star renowned for his fieldwork. Experts attribute his status to his hands-on approach, meticulous research and study, dogged determination, and clear focus of purpose. He saw a specific need and went after it. Marc Wilson, collection manager and head of the section of minerals at the Museum of Natural History, explains: “The major importance of Bryon’s collection is its near complete representation of localities within the commonwealth. It’s the best privately-owned collection of Pennsylvania minerals concentrating on the state’s mineral history and heritage for the last 50 years.” “ It’s the best privately-owned collection of Pennsylvania minerals concentrating on the state’s mineral history and heritage for the last 50 years.”

- Marc Wilson, Hhead of the Section of Minerals, Carnegie Museum of Natural HistoryIn this sense, Brookmyer followed in the footsteps once walked by Andrew Carnegie. From the very beginning, the industrialist recognized rocks and minerals as an important part of Carnegie Museums’ mission. In 1904, Carnegie himself purchased and donated to his Museum of Natural History William Jefferis’ 12,000-piece mineral collection, which features a suite of Pennsylvania specimens dating from the 1840s to 1900. More than a century later, the museum acquired the Pennsylvania mineral collection spanning from colonial times to the 1920s formerly owned by the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. The missing link? Specimens from the ’20s going forward. Enter Brookmyer, who took it upon himself to fill in those blanks. Long since having traded in his bicycle for a pick-up truck, Brookmyer thought nothing of driving for hours to track down a lead anywhere in the state. Prime locations included old mine tailings (leftover and scrap piles), highway or railroad cuts, and farm fields (before planting, of course)—in other words, wherever rock was or is in the process of being excavated.

Brookmyer always arrives prepared for battle. His weapons of choice are drills, shovels, chisels, pry bars, hand lenses, and maps. “It’s not what you see on the Flintstones,” he says. “And I’m not a big, he-man guy. I move rocks, carry a backpack, walk the drill in and out, and then walk specimens in and out.” It’s a muddy and dirty, physically demanding, and exhausting undertaking. But the work, when you can get it, is exhilarating, says Brookmyer. The truth is, he admits, “most of the time, you end up empty handed.” But when you do score, the results can be breathtaking—like the time he discovered stunning amethyst crystals. He unearthed the superstar of his collection in 1974. Brookmyer plucked the coal-black magnetite, one of only a few naturally occurring magnetic materials, from an iron ore deposit in one of his favorite spots in the southwestern part of the state. The specimen is currently a centerpiece in the museum’s Hillman Hall of Minerals and Gems. “The size and perfection of its dodecahedral [12-sided] crystals combined with its beauty makes this one of the premiere magnetite crystal specimens in the world,” Wilson marvels. “It would be an outstanding find anywhere, but for Pennsylvania, it’s unbelievable!” Not to be outdone is a stunning wavellite, an aluminum phosphate mineral found in small amounts at various spots around the world, with Arkansas being a prime source. Brookmyer’s Pennsylvania sample contains a spectacular cluster of beautiful lime-green wavellite balls. Wilson says that some of the most amazing calcite specimens in the world have come from Brookmyer’s field expeditions in the southwestern part of the state. One is particularly interesting, he notes, because it exhibits well-developed twinning in a single crystal.

A GOOD HOMEAfter decades of tedious and strenuous work, one thing Brookmyer likes to note is this: “What you see in the Hillman Hall of Minerals and Gems is far from what you find in the ground.” And the finished product takes even more time, effort— and lots of space. In addition to his tools (which for years have occupied his garage) and the dozens of specimen cabinets (which took up residence in the bedrooms), Brookmyer assembled an entire lab in his basement where he would painstakingly clean, trim, and catalog every single item he uncovered. Today, Brookmyer is married and the father of 5-year-old twins, Ian and Emily—something, he readily admits, that’s been a total “life changer.” Acknowledging that there are still specimens to be found and that he would still like to be the one to find them, his priorities have clearly shifted. In fact, where cabinets loomed large in his home there’s emerged a beautiful princess castle for his daughter. Those cabinets are now resting comfortably in their new home, the basement office of the museum’s minerals department. “It’s a truly remarkable addition to the museums,” Wilson says. Adding to its luster is the fact that the museum was able to purchase all 2,705 specimens (and the cabinets in which they were stored) below fair market value thanks to support from The Hillman Foundation and a type of planned gift known as a bargain sale. Because Brookmyer sold the specimens for less than what they’re worth in the name of education and research, he’ll have the opportunity to claim a charitable income tax deduction for the difference between the sales price and the appraised value—that is, for his gift to the museum. Brookmyer and his wife, Heather, are members of Carnegie Museums’ Cornice Society by virtue of this planned gift. “I’m quite proud,” Brookmyer says. “Things couldn’t have turned out any better. It means a lot that the collection is in a museum in Pennsylvania where people who live here can see it. And who knows, maybe it will light a fire in the next kid-collector.” From Wilson’s perspective, the arrangement “is mind boggling” but not unexpected. The pair has known each other since the late 1980s, when Wilson worked for the New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources. When he made the move to Carnegie Museums some 22 years ago, he reached out to Brookmyer for help. “Bryon is one of the most knowledgeable and successful collectors of Pennsylvania minerals,” Wilson says. “I asked his assistance in evaluating our holdings and advice on how best to continue to build on them.” Those consultations lead to a short-term agreement that has had a lasting impact. Initially, Brookmyer said he would loan the museum 234 of his best specimens for display in the Hillman Hall of Minerals and Gems for just five years. But every five years since, he’s renewed his commitment. These original specimens, centerpieces in the museum’s Pennsylvania display, were included in the sale and are now part of the museum’s permanent collection. This addition, says Wilson, establishes Hillman Hall as one of the finest mineral galleries in the world, and the museum as the destination of choice the world over for researchers and enthusiasts to view and study the products of Pennsylvania’s rich mineral heritage. From a personal vantage point, Brookmyer says the experience is humbling in more ways than one. When he and Heather plan a family outing to visit the museum and the collection that bears his name, he knows he’ll have to confront a hard truth. “My kids are more interested in seeing the dinosaurs,” he says. “They just don’t make a lot of cartoons about minerals.”

|

|||||||||||

Andy Warhol, Revealed · Picture This · Small Prints, Big Artists · Special Section: A Tribute to Our Donors · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Catherine Evans · About Town: A Legacy of Science · Artistic License: Home-field Advantage · Science & Nature: Big Blue · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |