|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Above, left to right: Andy Warhol, Upper Torso Boy Picking Nose, 1948-1949, © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. Andy Warhol, Three Figures in Back of Produce Truck, 1946-1947 © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. |

Andy Warhol, Revealed

In celebration of its 20th anniversary, The Warhol has reimagined its gallery spaces with a rehang that takes its cues from the life and times of Andy Warhol.

When he did venture out of his family’s South Oakland duplex, he would often head to one of the three neighborhood movie theaters where, for a nickel or two, he could lose himself in the movies. He adored movie stars, especially Shirley Temple. The thin, unathletic boy loved watching the cherubic, tap-dancing little girl who was born within a few months of him. Star-struck, young Warhol convinced his older brother Paul to write to the celebrities for their photographs and autographs. From 1939 to 1941, a time when World War II raged and steel mills spewed black smoke into the Pittsburgh air, he affixed the glamour shots of Buddy Moreno, Henry Fonda, Mae West, and Veronica Lake onto the black sheets of his scrapbook. His prized possession, coffee cup stain and all, was a large color photograph, inscribed “To Andrew Warhola, from Shirley Temple.” Today, the beautifully-preserved scrapbook rests inside a display case on the seventh floor of The Andy Warhol Museum. The North Side palace of Pop art is celebrating its 20th anniversary with a dramatic rehang of its collection galleries, telling the story of Warhol chronologically—through art, memorabilia, and re-creations—for the first time. A Pittsburgh Kid

A Young Andy in New York

The reimagined galleries reveal many such artifacts of Warhol’s life, from his working-class Pittsburgh background to his New York stardom at The Factory and beyond. It’s a fresh, decade-by-decade exploration that brings together the many facets of Warhol’s work—film, video, television, and music. It all begins on the seventh floor, with stories of young Andy. It ends on the second floor with a new space for traveling exhibitions and a nod to Warhol’s lasting impact on artists that came after him. “It’s a new framework to craft the narrative,” Shiner says. “People were always afraid of the idea that a chronological hang would equal a mausoleum, that it would be static. Luckily the collection is so large and vast, we can always show new things.” From the day The Warhol opened in May of 1994, it’s been faced with the challenge of how to focus on a single artist without becoming a shrine. “At the time, we asked ourselves, if you visit once and see it, why come back?” says John W. Smith, director of the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, who was the interim director of The Warhol during its debut and spent 11 years there, much of it as assistant director for collections, exhibitions, and research. “We realized we had to develop exciting and dynamic programming.” It helps that the portrait of Warhol is ever-evolving, even 27 years after his death. “We’re trying to impart the idea of the multiplicity of Andy Warhol, both in terms of who he was and the kinds of things he produced,” explains Nicholas Chambers, the Milton Fine Curator of Art and lead architect of the top-to-bottom rehang, which took two years to execute. “Warhol was ambitious at 20,” Smith says. “What’s exciting to me is that The Andy Warhol Museum is as ambitious at 20 as it was when it first opened.” THE CHOSEN ONEAndrej Warhola, a construction worker who emigrated from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, scrimped and saved enough to bequeath $1,500 to Andy for his art education at Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon University). The yellowed document, on loan from the Warhola family in Pittsburgh, is on public display for the first time. As the youngest of Andrej and Julia’s three sons, Andy was considered the best bet for college and the child most likely to support the rest of the family, says Shiner, a prediction that turned out to come wildly true. But Warhol (who dropped the second “a” in his name in the 1950s so it sounded less ethnic) almost flunked out of his first year of art school, and was put on academic probation. “They thought his drawing was too primitive, too avant garde,” Shiner explains. The Pop Artist Emerges

“Warhol was ambitious at 20. What’s exciting to me is that The Andy Warhol Museum is as ambitious at 20 as it was when it first opened.”

- John W. Smith, Director of the Rhode Island School of Design Museum

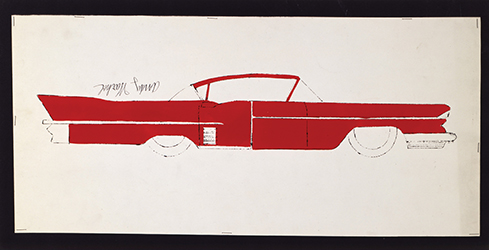

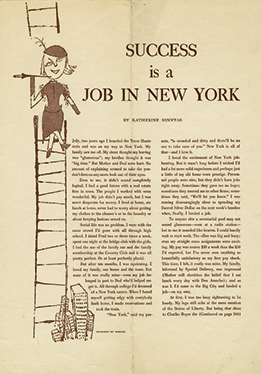

“He did a style more in line with what was considered beautiful drawing at the time,” adds Shiner, pointing to the fruit truck paintings along a wall on the museum’s top floor. While the fruit stand paintings were conformist by Warhol’s standards, he drew outlines of the women’s breasts and buttocks through the sheer fabric of their dresses. He also worked hard at figuring out the system. “He had an extraordinary work ethic,” Chambers says. “He always studied the world where he wanted to succeed, be it art school or the art world.” By his senior year, confident in his own ability, Warhol started to thumb his nose at the art establishment with his Nose Picker series. In 1949, his painting titled The Broad Gave Me My Face, But I Can Pick My Own Nose was rejected by the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh for its annual exhibition of local artists, but it was the star of a show of rejected works, exhibited elsewhere. Today, Nose Picker 2, a primitive-looking boy with a finger in his nostril, is on display at The Warhol—an early sign of the artist’s contrarian sense of humor. THE GO-GETTERAfter graduating from Carnegie Tech, Warhol moved to New York City, taking in the artistic energy of the city filled with not only American artists but Europeans who had immigrated to escape the war. A largerthan- life photo reproduction on the museum’s seventh floor shows a jaunty and suited Warhol upon his arrival in New York in 1949. He looks ready to take on the world—and he did, making endless cold calls to magazine editors. Warhol learned all about pounding the pavement from his mother, Julia. A folk artist, she sold metal flowers fashioned out of Campbell’s Soup cans door-to-door. “The boys would hide in the bushes and watch her,” Shiner says. All three inherited her knack for rustling up work. Shortly after arriving in New York, Warhol was contracted as a commercial artist by Glamour magazine. The Warhol showcases his very first paid illustration, which accompanied a story in the magazine titled, What is Success? It was a question Warhol would answer on a global scale. And the subhead of the story—Success is a Job in New York—is something Warhol definitely took to heart.The Business of Being Andy

“ People were always afraid of the idea that a chronological hang would equal a mausoleum, that it would be static. Luckily the collection is so large and vast, we can always show new things.”

- Eric Shiner, Director of The Warhol

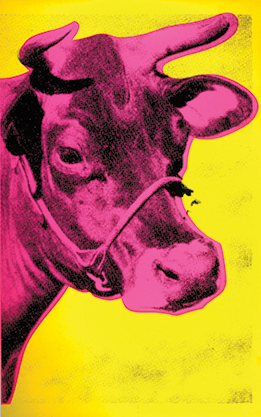

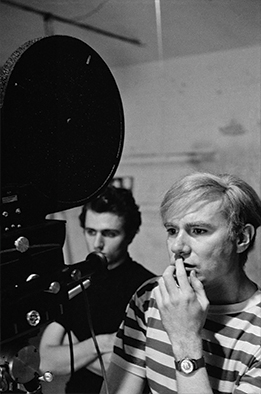

His newfound prosperity also turned Warhol into a collector of fine art, starting with a drawing by Jasper Johns. But it wasn’t enough for Warhol. His drawings may have been in households throughout America, but his name wasn’t. “Warhol wanted to be famous,” says Shiner. That lightning-bolt fame came in 1962, when the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles hosted a show of Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans, an exhibition that both electrified the art world and elicited disdain. His star grew as he made silkscreened celebrity portraits— now on spectacular display on the museum’s fifth floor—in his New York studio, The Factory. Visitors to The Warhol get a taste of The Factory vibe with the bricks painted silver in the renovated first-floor and in a new home for the Silver Clouds installation, Warhol’s famous floating Mylar balloons, a visitor favorite. A ONE-MAN MARKETWarhol was obsessed with new media, and using it to document his life and world. From Polaroids to his ever-present audio tape recorder; and, from the time he got his hands on his very own movie camera in 1963 until his death, film and video. In 1966, he decided to use current technology to create the Exploding Plastic Inevitable (EPI), his raucous multimedia roadshow that took in $18,000 in its first week, featuring ear-splitting musical performances by the Velvet Underground and Nico while films and handmade slides beamed from multiple projectors. “It was an over-the-top, assaultive environment,” explains Greg Pierce, the museum’s assistant curator of film and video. Warhol was behind the scenes controlling the first EPI performances in New York, but then sent his crew on the road to create the attention-grabbing shows in other cities across the country. “It got him a lot of publicity,” Wrbican adds. “It got a lot of terrible reviews but it wasn’t all terrible. It depended on the reviewer and how hip he was to the culture.” While Pierce couldn’t replicate an EPI show exactly, he did transform part of the museum’s sixth floor into what he calls an “evocation,” with the drone strums of the Velvets pumping through the gallery. Add to that a mirror ball, digitized copies of slides from the original performance, and nine reels of Warhol films, all surrounding visitors simultaneously. To give it an authentic feel, two of Warhol’s EPI Background Reels, remastered in digital format—Velvet Underground and Gerard Begins—are among the key elements of the experience. “This is the first time they’ve been shown since 1966,” says Pierce.

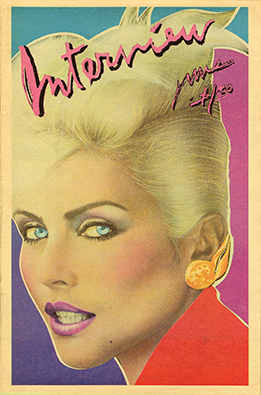

Warhol demonstrated his own ferocious work ethic throughout his life. In 1972, he made his famous Chairman Mao portraits, which marked his return to painting and now hang on the museum’s fourth floor against a backdrop of Warhol’s bright-purple Mao wallpaper. And for the first time, the materials he used to create one of his most radical works of art—due to method and not subject—are on public display. These never-before-seen Mao graphite drawings, several photocopies of the drawings, and the acetate that was the source image for both the drawings and the unusual editioned print that followed are among thousands of artifacts plucked from the artist’s storied Time Capsules, 610 brown cardboard boxes, metal filing cabinets, and steamer trunks into which Warhol stashed objects both mundane and invaluable. Now understood to be a massive work of art, the Time Capsules are still being carefully catalogued by museum staff. What this reveals, says Wrbican, is that Warhol defied one of the primary definitions of an editioned print by the simple act of making a copy of a copy, repeatedly, using a standard analog office photocopier. This resulted in the creation essentially of more than 300 prints which are totally unique (rather than being distinguishable only by their unique assigned number in the edition). “They were made in a strange way, serial copying, so that each one became more elongated and distorted,” explains Wrbican. “After several dozen copies, it became abstract.” In the newly renovated archives area on the museum’s third floor, visitors can get an up-close glimpse of decorative art objects such as a radio designed by architect and industrial designer Walter Dorwin Teague (1936) and a stunning etched-glass vase (maker and year unknown, but possible Czech, 1920s) from the museum’s archives that sat in storage, seen only by museum staff, for 20 years. They’ll be displayed alongside other pieces of Pop art history that have been unearthed in Warhol’s Time Capsules, with rotating views of the latest finds. Over the years, they’ve revealed everything from Clark Gable’s slightly worn two-tone spectator shoes to Warhol’s lovingly-worn copy of Judy Garland’s soundtrack to A Star is Born—its box half crushed, its grooves played out—providing a clearer picture of the artist’s true musical tastes. THE BEAUTY OF BUSINESSWarhol’s businessman persona became even more pronounced after Valerie Solanas shot and nearly killed him on June 3, 1968. As a result, over the next several years he dropped some longtime Factory dwellers, leading to much bitterness. Soon after, some of the remaining Factory insiders renamed his workspace “The Office.” A new fifth-floor installation evokes its spirit, showcasing items like the black push-button phone flecked with paint that Warhol cradled as he chatted with his famous friends. Visitors can also glimpse for the first time the artist’s 1985 appointment book and Rolodexes with contact information for the likes of Lou Reed and film director George Cukor. These tools of the trade are exhibited near Warhol books and Interview magazines, a publication he co-founded in 1969. On the walls hang portraits of Warhol’s key staff who helped the prolific but disorganized artist churn out art. And the same stuffed harlequin Great Dane named Cecil that guarded The Factory’s front door from 1969 to 1987 now stands at attention inside the new museum space. Before he became the stuffed dog among hipsters, the canine, born Ador Tipp Topp, was a champion at the 1924 Westminster Kennel Club Show. He was stuffed a decade later by Ralph Morrill, known as a genius taxidermist who worked at Yale University. Warhol, who once said he never met an animal he didn’t like, stumbled upon the regal-looking pet at a New York antiques shop. The shop owner told him it was Cecil B. DeMille’s dog and Warhol paid $300 to take him home. Turns out the famous film director had never owned the dog, but Warhol believed the story, named the dog Cecil, and gave him a part in his book, Factory Diaries. Many of the ideas incorporated into the massive rehang are the result of 20 years of collaborations on Warhol exhibitions around the world, from Arkansas to Moscow. “We loved that the 15 Minutes Eternal show that has been touring Asia includes examples of the type of equipment that Warhol used to make his work, from Polaroid cameras to screens to paints and papers,” says Shiner. “It’s a new part of Andy’s universe to bring to Pittsburgh.” Like its namesake, The Warhol is a work in progress. As Chambers puts it, “There is no singular story to tell about Andy Warhol.”

Support for the rehang of the museum’s permanent The Warhol would also like to recognize the following Jet Setter Sponsors First Class Sponsors Gold Preferred The Warhol also recognizes PNC Financial Services as

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rockhound · Picture This · Small Prints, Big Artists · Special Section: A Tribute to Our Donors · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Catherine Evans · About Town: A Legacy of Science · Artistic License: Home-field Advantage · Science & Nature: Big Blue · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |