|

||||||||||||||||

|

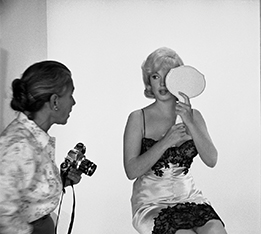

This installation by Erik Kessels, 24 HRS in Photos, compiles all of the images uploaded to the popular site, Flickr, in a single day. Photo: Gijs Van Den Berg (Les Recontres D’Arles Photographie) |

Picture This

Through its Hillman Photography Initiative, Carnegie Museum of Art has set out to answer the question: What is photography today? As ubiquitous as the smartphones used to capture them, photographs are everywhere, taken by just about everyone. Do they all matter, and who decides if they do? Photography curator and author Marvin Heiferman, editor of Photography Changes Everything and one of the Initiative’s internationally renowned collaborators, talks about why this participatory endeavor matters, and how the discussions it’s setting into motion are needed now more than ever. As a curator and writer on photography, and someone who takes and stores a lot of pictures on the phone in my pocket, I am fascinated by the types of stories about visual culture that I come across on a daily basis. That people are thinking, talking, and writing more about photography lately is not surprising, given how many pictures are taken. In 2014, it’s estimated that 2.4 billion photographs will be made every single day. If digital technology has helped turn each of us into photographers, we have all, by default, become photo editors, image manipulators, critics, and archivists as well. Photography may once have been the way to mark and celebrate special events; today, it’s just an everyday experience, another way we now share and communicate with each other. And yet even if photography has, in one sense, become nothing special, what remains remarkable is the fact that the medium never loses its extraordinary capacity to inform, startle, and delight us. Earlier this year, I was fascinated by a New York Times article about a $1,200 domestic drone in which the writer described opening up a bulky box, extracting a picture-making flying machine from it, puzzling through its complex instructions and, ultimately, having a great time testdriving his sophisticated new toy. “Oh, my goodness, this thing is fun,” he said, summing up the experience. And I bet it was. But I’m also keenly aware of other kinds of drone stories, the ones that don’t have such consumer-friendly or happy endings. What fascinates me lately, having worked in the photography field for decades, is that as picture-taking and photo-sharing become increasingly democratized and impactful, not enough dialogue about photography seems to be going on. This may seem hard to believe. There are, one might argue, ample opportunities—in museum exhibitions, magazines, journals, books, blogs, how-to courses, and at conferences— to look at, question, and argue for the medium. But surprisingly, the ways photography actually functions in the broader culture and scheme of things—how it is employed, who and what it represents, and why it works so powerfully and well— remain underexplored. Perhaps that’s because, with so many images being made by so many people for so many reasons, it’s impossible to construct or support any single or seamless story about photography. The kinds of pictures and photo-driven narratives that capture attention and go viral—such as the international spread of and chatter around President Obama’s selfie at Nelson Mandela’s funeral late last year—only hint at how deeply photographic imaging is embedded in and actively shapes knowledge, everyday life, and the world at large. “If photography is increasingly understood to be a powerful

agent of cultural and social change, why not sign on to investigate and advocate for that?”

Since its introduction in the 19th century, the art and artfulness of photography has been cyclically argued for and argued over. Carnegie Museum of Art was, in fact, among the earliest of American museums to grapple with it in its pioneering display of art photography in Photo Secession, the historic 1904 exhibition of pictorial imagery that was organized by photography innovators Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen. Throughout the 20th century, more art museums in the United States would come to recognize and support the medium, or at least their quite intentionally rarified version of it, by focusing largely on the photographs made as art. But what about all the rest of them? The much-heralded photography boom of the 1970s made it seem as if the medium, a century and a half after its introduction, had come of age. But even that transformational moment failed to calm down the nervousness that seems to perpetually hover around photography. With the democratization of digital imaging in the 21st century, and as photography is once again in the process of being radically reimagined, cultural institutions, and art museums in particular, find themselves in a curious position. They can move forward on the photographic paths they have staked out for themselves or bob in the wake of exhibition and collecting models developed elsewhere. Or—and this is where things get interesting—museums can, in this time of flux, rethink their relationship to and broaden their inquiry into a medium that reengineers itself and, as it does, reshapes our need for and expectations of representation itself. It is Carnegie Museum of Art’s decision to take the latter course that made me jump at the chance to become one of the first round of “agents” chosen to steer the early programming and course of the Hillman Photography Initiative. The word agent (I’ve got to admit) at first sounded like a strange way to describe who we were or what we might do. As it turns out, it’s pretty accurate. If photography is increasingly understood to be a powerful agent of cultural and social change, why not sign on to investigate and advocate for that? Initiative, too, is an interesting word, one that suggests ambition, reassessment, a desire to forge ahead to make new things happen. That is what’s made working on the Hillman Photography Initiative a unique opportunity for the initial group of us— artists, curators, writers, and a technologist, together with the museum’s Tina Kukielski and Divya Rao Heffley—to create a year’s worth of innovative programming.

THIS PICTUREThe project I’ve helped develop is This Picture, which explores how images have profound personal, social, and cultural meaning and are central to the shaping and conduct of our lives. Instead of following a more conventional and top-down curatorial model, This Picture asks a broad public audience to explore how photographs work and question what makes them attractive and important to us. Each month for the next year, the museum will use various media and distribution channels to present a single provocative image and ask viewers to stop, consider, and respond. The responses—which may include texts, photos, videos, and audio files—are being collected online. It is our hope that together they are creating a platform for an unprecedented and lively conversation about photography. We’re exploring not just what is visible in a photograph, but what lies beneath its surface. We ask those who participate to consider what might cause a photograph to be made, have impact, and be remembered. What any single person sees in any single photograph reveals something about who they are, what they see, and what they care about. Collectively, we want to acknowledge the multiple meanings photographs can have and talk about the multiple lives they live in our increasingly digitized world. “The more we are able to read images and understand how they work within our culture,” the artist John Baldessari said a few years ago, “then the more empowered we will be as individuals.” And so as part of This Picture, we encourage the public to think about how images capture attention, reflect values and intentions, and trigger response. As part of this effort, the museum’s education department is reaching out to area school teachers who we hope will use this project to help build visual literacy. While photography, as so many have noted, freezes time, it is equally important for us all to acknowledge that the form, meaning, and our relationships to photographic images keep changing. What is, perhaps, most ingenious about the structure of the Hillman Photography Initiative is that it’s engineered to keep changing as well. Each year a new round of agents will be recruited to rethink photographic imaging and priorities in different ways. “Given the powerful ways the medium speaks to, for, and about us,

we need to make more urgent and rigorous efforts to address photography and how it functions.” In the 21st century, and as every aspect of photography evolves—its definition, materiality, impact, and audiences—there is a broad cultural imperative and an ever-greater practical need to acknowledge what the medium has been, is, and may become. To get a clearer picture of how a photograph works and to gain perspective on what visual literacy both means and demands of us, we need to encourage more open and interdisciplinary conversations about how photography operates, where the power of images comes from, and what their significance is. The astounding number of digital images made daily underscores the fact that photography, no longer an incidental but a daily event, plays an active and central role in determining who we are, what we want, and what we will say and do. Given the powerful ways the medium speaks to, for, and about us, we need to make more urgent and rigorous efforts to address photography and how it functions. In order to do that, not only does the public dialogue around photographic imaging need to shift, but we have to rethink where that dialogue will be hosted and can take place. That’s what got me excited by and involved in the Hillman Photography Initiative. At a time when the field of photography is being radically transformed, and as many art museums are choosing to wait things out or host decorous discussions about what’s happening in photography, Carnegie Museum of Art has chosen to stake out a bolder path and a more active leadership position in the field. What an honor to have an opportunity to be a part of that. And, what a relief. The Hillman Photography Initiative, a special project within the photography department of Carnegie Museum of Art, is supported by the William T. Hillman Foundation and the Henry L. Hillman Foundation.

At Play in the Sandbox

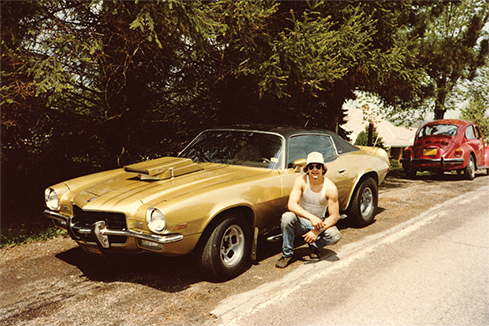

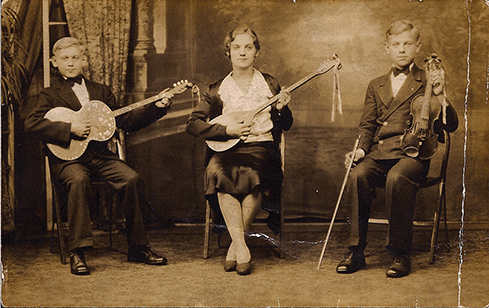

Your grandmother’s wedding photo. Your first car. That precious first taste of spring on the Schenley Park lawn. Melissa Catanese and Ed Panar want your snapshots, Pittsburghers. The kinds of memories—made in and about the region—you might rescue if your home was six feet under water. From those beloved images the artists plan to craft a family photo album of the city. “Everyone has photographs that are close and dear to them,” says Catanese. “That’s what we want to tap into—how photographs are important to others and why; what are the stories behind them.” Dubbed A People’s History of Pittsburgh, this idea to create a collective portrait of Pittsburgh has been marinating with the photographers since they first moved to the city seven years ago by way of a northern suburb of Detroit, where the pair met in graduate school. Now, as artists-in-residence at Carnegie Museum of Art as part of its newly launched Hillman Photography Initiative, they’re giving it legs. And already city dwellers have answered the call, capturing everything from a Pens-themed wedding day to an early morning mother-and-son-breakfast at DeLuca’s Diner in the Strip. (Contribute and search the archive online at nowseethis.org or bring hardcopies to the museum on June 26 and July 24 to be scanned.) At the end of the yearlong project, Catanese and Panar— owners of Spaces Corners, Pittsburgh’s only bookstore dedicated to photography books—will curate the images into a physical photobook, a thriving art form particularly among professional photographers. But first, through July 28, the pair is introducing Museum of Art visitors to photobooks of all kinds through their installation, The Sandbox: At Play with the Photobook, which is part reading room, part studio, part event space. “It’s a space where we want people to feel free to explore and discover,” Catanese says, noting that she and Panar will be at the museum Wednesdays through Saturdays (3-8 p.m. on Thursdays.) “When you were a child, you could throw sand around and let the imagination run wild in the sandbox. We look at photographs all the time, so we kind of take for granted how they can provide that strange and awesome experience of being transported to another place or time or feeling. This project is a creative reminder.” Every two weeks they’ll rotate themes, hosting events and inviting visitors to explore topics as diverse as time and place, puzzles, social studies, and science fiction through intimate groupings of images in photobooks, which Panar describes as a collaboration between the artist, subject matter, and reader. “A good photobook, which some people describe as paper movies, takes you on a journey and will never be the same experience twice,” says Panar, who recently created 100 such mini-vignettes titled City Atlas—handmade and inkjet-printed— with 100 more to come. His project, he says, “is an absurd encyclopedia of objects you can encounter in a place”—in this case, Pittsburgh’s hidden nooks and crannies discovered by the Johnstown native in his quest to explore all 90 of Pittsburgh’s neighborhoods by bicycle. “Photobooks are the gateway drug to buying art,” adds Panar. “For $15 to $85, photobooks are collectible, democratic, accessible, and affordable. They’re also an ideal way to look at photographs.” - Julie Hannon

|

|||||||||||||||

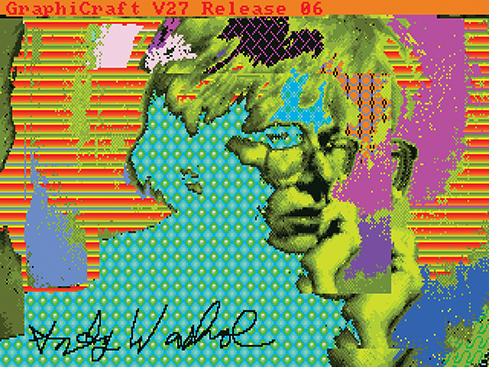

Andy Warhol, Revealed · Rockhound · Small Prints, Big Artists · Special Section: A Tribute to Our Donors · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Catherine Evans · About Town: A Legacy of Science · Artistic License: Home-field Advantage · Science & Nature: Big Blue · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |