|

|||||||||||

|

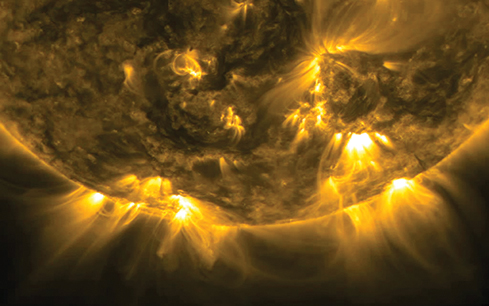

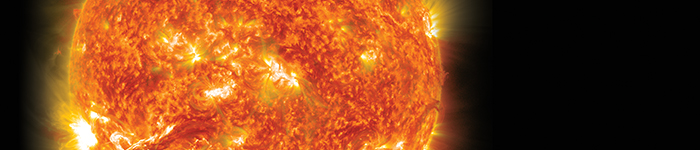

That which gives power can also take it away. Solar flares, which are often followed by massive magnetic eruptions of plasma known as coronal mass ejections, can wreak havoc on Earth-bound GPS systems and aviation navigation systems. PHOTOS: Solar Dynamics Observatory/NASA |

Sun Struck

As the Sun rises due east for the spring equinox, Carnegie Science Center celebrates life with our unpredictable “neighborhood star.” Talk about a magnetic relationship. At a distance of 93 million miles, the Sun exerts a sizzling, powerful pull on our planet that’s been unabated for more than four billion years—and, by all estimates, will remain so for another five billion. The vast gap, bridged in a mere eight minutes by sunlight that reaches Earth, turns out to be the ideal distance to support human life. All the while the Sun centers a vast plain of eight planets, at least five dwarf planets, hundreds of thousands of asteroids, and as many as a trillion comets. Mike Hennessy, Carnegie Science Center’s longtime education program developer, describes Earth’s position relative to the Sun as “the Goldilocks zone”: not too hot (like boiling Mercury and Venus), not too cold (sorry, Mars), but just right.

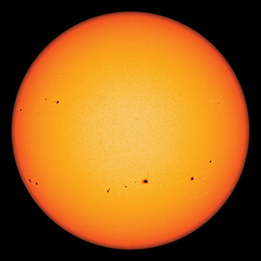

“The Sun drives our weather, ocean currents, seasons, and climate,” says Hennessy. “And it’s the Sun that starts photosynthesis, with red and blue light from the spectrum being absorbed by leaves.” Shielded from the Sun’s enormous power by its own magnetic shield and atmosphere, Earth sustains carbonbased life with its precious combination of elements. That’s not to say, of course, that the Earth isn’t vulnerable to the Sun’s volatile nature. Made up of about 91 percent hydrogen and nearly 9 percent helium, the Sun is a massive nuclear reactor producing unimaginable amounts of energy through the fusion of light hydrogen atoms into heavier helium. Continuous atomic explosions eject energy outward, superhot plasma roils its interior, and shifting magnetic fields further disturb its surface, causing sunspots. “The Sun drives our weather, ocean currents, seasons, and climate.”

- Mike Hennessy, Education Program Developer, Carnegie Science CenterThis fierce and constant turmoil creates space weather. And while the surface of Earth is protected from the high-energy particles and radiation produced by major Sun events like solar flares, changes in radio waves can disable Earth-bound GPS systems and aviation navigation systems. Geomagnetic storms have crashed city-wide electric power grids, like the 1989 blackout that left nine million people in the dark in and around Quebec. Even a glancing blow from the Sun can shake Earth’s magnetic field, nudging the Northern Lights into view in lower U.S. latitudes, as happened in 2011. As a way to help the public understand the crucial role this at once familiar and strange “neighborhood star” plays in the solar system, the Science Center developed SolarQuest: Exploration of the Sun-Earth System, a new planetarium show and traveling education program that brings the Sun-Earth relationship into focus with dazzling imagery. “Our storyline basically traces the journey that a photon of light takes from the Sun’s core out into the solar system and then hitting the Earth,” says Hennessy. “We begin with the Sun’s nuclear fusion, talk about how radiation takes thousands of years to make its way to the surface of the Sun, before shooting out, and then, eight minutes later, jumpstarts reactions in Earth’s atmosphere such as the aurora borealis and seasonal change.” The Science Center is one of several dozen U.S. science institutions awarded sizeable grants from NASA to create innovative interpretations of heliophysics, an environmental science that combines meteorology and astrophysics in its examination of how the Sun affects the solar system. Awarded $765,000, the Science Center is the only institution using its grant for a traveling theaterstyle assembly program, part of its popular Science on the Road program, which reaches some 200,000 regional PreK to eighth grade students a year. Hennessy believes there’s no substitute for live action.

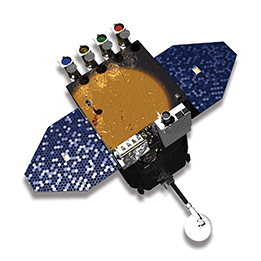

“Theater is a powerful gateway for inspiration, to get a large number of students interested in space science,” says the 16-year Science Center veteran. “There’s power in telling science like a story.” The stunning 10-minute planetarium show, which debuted in the Science Center’s Buhl Planetarium last July, is the centerpiece of this latest Science on the Road offering, thanks to a portable digital planetarium also funded through the grant. Drawing on real-time data generated by the Solar Dynamics Observatory, a research satellite launched by NASA in 2010 to observe the Sun 24/7 for five years, SolarQuest examines the Sun’s often unpredictable behavior. It helps audiences of all ages make some sense of it all: What events trigger changes in solar activity? How does Earth and its protective magnetosphere respond? And what are the impacts on us Earthlings? Sunspots and Solar CyclesFor most of human history, peering inside the Sun’s interior was impossible. Galileo, who had already proved the theory of heliocentrism (placing the Sun at the center of the universe), reported the existence of sunspots in the early 17th century. Today we know that these planetsized dark spots on the surface of the Sun form whenever the Sun’s magnetic fields rupture. Electrical currents deep inside the Sun twist and tangle these strands until they become unstable and explode, sending streams of energy into space.

At the close of 2013, the Sun emerged at the peak of its decade-long cycle as expected, with daily spectacular sunspots and solar flares. But only a few years earlier, at the low point of the cycle, sunspot activity not only was suppressed, but seemed to be obliterated. Between 2008 and 2009, sunspots almost completely disappeared and solar activity suddenly dropped to hundredyear lows. Earth’s upper atmosphere cooled appreciably. The Sun’s magnetic field weakened, allowing cosmic rays to penetrate the solar system in record numbers. Space junk decayed more slowly and started accumulating in Earth’s orbit. “That absolutely stumped physicists,” says Malerbo. Researchers doing computer modeling of the event now believe the culprit was a shift in plasma currents, which suppressed sunspot formation. “The Sun contains huge rivers of plasma similar to Earth’s ocean currents,” Malerbo explains. “Those plasma rivers affect solar activity in ways we’re just beginning to understand.” NASA’s 21st-century satellites, armed with sophisticated telemetry and spectroscopy, have allowed heliophysicists to infer the complex activity below the solar surface. Just as an ultrasound examination allows doctors to look inside the human body via sound waves, new technologies probe the belly of the sun. “Because the solar interior is opaque, we must devise sophisticated measurements,” explains Barbara Thompson, coordinating scientist for NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory at Goddard Space Center in Maryland. Previous solar missions transmitted information periodically, but the Solar Dynamics Observatory never stops. It collects 130 megabits of data per second— the daily equivalent of a half-million digital songs—and streams it directly to a ground station in the New Mexico desert. Once received, it’s available to scientists worldwide. The vast amounts of resulting data are a treasure trove for solar scientists of all stripes. “The old model was to simply collect data,” notes Thompson. “Now, part of NASA’s mission is making data accessible. It’s truly an international effort. We’re not just serving data—we provide tools and information to manipulate data and produce results.” Now in the works for 2018 is a satellite that will fly to the Sun’s surface and transmit data until high temperatures ultimately destroy it. In the meantime, while seismologists comb current-day data for signals of plasma flows and explosions from the solar interior, other experts analyze every last morsel of available data. “Magnetic field people do an incredible amount of magic,” Thompson says. “They turn protons into precise information about processes happening 93 million miles away.” “The Sun is unpredictable,” Malerbo says. “By studying the solar cycle using the latest technologies, we’re learning as much if not more than we do in manned missions.” Hennessy agrees, adding: “We have a pretty good handle on how the Sun affects overall climate and processes on Earth. But as our technological world advances, we have more work to do to understand and predict the Sun’s variability.”

Did You Know?

|

||||||||||

Unraveling Race · Silver & Suede · The Tedious Intrigue of Art Conservation · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Nicholas Chambers · Artistic License: The Science of Sculpture · Science & Nature: Nature as Classroom · About Town: Friends of the Forest · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |