|

||||||||||||||

|

How would the U.S. Census classify you? As is printed on these college students’ t-shirts, the answer to this question has continually changed since the census began in 1790, reflecting changing ideas about race in American society. All Images Courtesy of American Anthropological Association and Science Museum of Minnesota |

Unraveling Race

A new exhibition challenges us to forget everything we think we know about the man-made concept of race. There is no denying the power of race to influence laws and policies, attitudes and experiences, opportunities lost and opportunities gained. The story of America is also in large measure the story of race. And it can be told through the U.S. Census. In 1790, the inaugural census asked Americans to identify themselves using the following classifications: Free White Males 16 years and upward; Free White Males under 16; Free White Females; All Other Free Persons; Slaves. As the decades passed, the question regarding race was revised, modified, and rephrased to include and then ultimately exclude the terms colored, mulatto, quadroon, and octoroon. Fast forward to the most recent survey taken in 2010 which includes a “mark one or more” option for race, allowing for 63 possible racial combinations, plus a write-in option for “some other race.”

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, information on race is required for many federal programs and is critical in making policy decisions, particularly those related to civil rights. States use the data to meet legislative redistricting principles, promote equal employment opportunities, and assess racial disparities in health and environmental risks. Yolanda Moses, professor of anthropology and the associate vice chancellor for diversity, equity and excellence at the University of California, Riverside, sums up the propensity to base certain decision-making on race this way: “Countries that use race as a marker on censuses are countries that have a history of slavery.” To that point, language on the last census questionnaire admits that its own racial categories “generally reflect a social definition of race recognized in this country and not an attempt to define race biologically, anthropologically, or genetically.” There is one question the census fails to consider—the question at the heart of an upcoming traveling exhibition opening March 29 at Carnegie Museum of Natural History: Are we really so different? Developed by the American Anthropological Association (AAA) in collaboration with the Science Museum of Minnesota, RACE: Are We So Different? boldly explores the idea of race through the lenses of history, human variation, and lived experience. The Story of RaceSince its launch in 2007, more than 30 venues large and small, in urban and not so urban settings, in all corners of the country have presented RACE: Are We So Different? Among them: the Institute of Texan Cultures, Kalamazoo Valley Museum, the Louisiana State Museum, the University of Northern Iowa Museums, and the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. It all started with a series of conversations. When Moses was AAA president in the late ’90s, she encouraged her colleagues to think about how the organization could make a difference beyond the world of academia and research. “We wanted to become more publicly engaged and deal with social issues,” she recalls. “We thought we could look at race, what it is and what it isn’t, and be very instrumental in changing the way people talk about it.” Moving it from idea to reality took time, funding, and vision. With Moses at the helm, the input of a 25-person advisory board, and contributions from 17 different professional disciplinary associations, the path forward began to take shape. “It’s been a collaboration between scientists, historians, policy makers, and legal scholars,” she says. Along the way, the exhibition has met with resistance. “At first,” Moses says, “museums didn’t want it. They saw it as controversial, that it would upset donors and make people uncomfortable.”

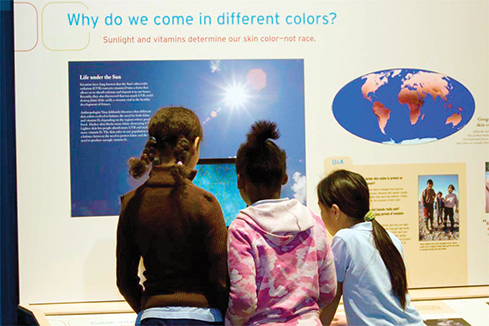

Nina Jablonski, a distinguished professor of anthropology at The Pennsylvania State University, understands why. “Race is a messy concept, it is vague and slippery. It always has been and still is. It’s a topic most people prefer to ignore.” Not Jablonski. A biological anthropologist and paleobiologist, she has devoted much of the last 25 years of her career to studying the evolution of human skin and skin color. She’s found that skin pigmentation has nothing to do with race and everything to do with the ultraviolet radiation from the Sun. Dark skin evolved as a means of protecting humans from the Sun’s damaging effects. As people migrated away from the Equator, their skin began to adapt by producing vitamin D and, consequently, losing pigment. Add to the mix the natural inclination of humans to mingle and mate, and the spectrum of color is amazingly diverse. “There is a tremendous amount of variation between skin color within ‘racial’ groups,” Jablonski notes. “Race is a messy concept, it is vague and slippery. … It’s a topic most people prefer to ignore.”

- Nina Jablonski, Professor of Anthropology at the Pennsylvania State UniversityLooking in the mirror and at each other, millennials may be starting to view race in just that way. “Younger, self-proclaimed mixed-race people don’t want the old templates,” she says. “They are refusing to tick the race box.” After all, as Jablonski points out, those boxes or labels aren’t neutral. “The label itself becomes a destination, a guidepost for expectations.” Only Skin DeepSo what does race sound like? In one of the exhibition’s many interactive stations titled “Who’s Talking?,” visitors are asked to identify someone’s race simply by listening to them speak. The results are almost always surprising. Another station, “The Colors We Are,” invites visitors to scan their own skin and view it amid the wide array of human skin tones. The 5,000-square-foot exhibition shares some compelling personal stories, too. “We All Live Race” features a variety of people— a Korean girl adopted by a white family, a Mexican girl who says she “passes” for white —talking about race. “Youth on Race” tells the story of high school students and their lives inside and outside of the classroom. In “A Girl Like Me,” a video also featured on the exhibition’s website, teen filmmaker Kiri Davis sheds light on the damaging messages sent to African American girls about their worth as human beings, all based on their physical attributes. One of her subjects, Stephanie, recounts how her mother once warned her about looking “too African” when she let her hair go natural rather than straightening it. “Well, I am African,” exclaims Stephanie, defensively—and what’s wrong with that? A large floor map in the RACE exhibition provides an interactive centerpiece for lessons about human migration, gene flow, and the continuous distribution of human traits across the globe. An animation dubbed “African Origins” shows how humans emerged from Africa and then spread to populate the world. Other components challenge beliefs about distinguishing people by race—that sense of I know a German when I see one. One game invites visitors to sort people according to traits that scientists historically used to demarcate races. When these categories fail, visitors learn about the inadequacies of such outdated theories. After all, the exhibition reminds us, two random Koreans are as likely to be as genetically different as a Korean and an Italian. And in one simple, sobering moment, piles of cold hard cash show in graphic form the vast wealth disparities between whites and other ethno-racial groups. “People who didn’t come to the museum together were talking to each other, and they were talking about race.”

- Joanne Jones-Rizzi, Exhibition DeveloperRACE: Are We So Different? defies conventional wisdom by stating unequivocally that race is a social construct, and a relatively new one—just a few hundred years old—at that. It declares the concept of race as manmade, created as a means for people with wealth and power (like conquerors and colonizers) to maintain their wealth and power. It explains that because human populations are not biologically distinct from one another, race has no scientific merit. Still, it’s a force to be reckoned with. A Conversation StarterOn January 10, 2007, RACE made its debut at the Science Museum of Minnesota. At the time, Joanne Jones-Rizzi, one of the show’s developers, kept her expectations in check. “It was such a huge endeavor and the content is so charged,” she says. “People were skeptical.” But if you build it—and offer free admission— they will come. Thanks in part to a grant offering everyone a free pass on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, expectations were exceeded. On that one day alone, attendance hit the 6,000 mark. “It was just remarkable,” Jones-Rizzi recalls. But perhaps what was even more remarkable was that people started talking, to their friends and family and to complete strangers. Jones-Rizzi credits the different videos throughout the exhibition with helping to break down barriers. The short films feature scholars and historians talking about their work, as well as real people—young and old—sharing their lived experiences. “Those voices provided the catalyst for our visitors to talk,” Jones-Rizzi says. “People who didn’t come to the museum together were talking to each other, and they were talking about race.” The same phenomenon occurred in other museums. At the Smithsonian in 2011, Washington, D.C. public school teacher Abigail Klein saw people get emotional about their personal connections to the materials in the exhibition; others expressed their suspicions and anger. As a volunteer docent, Klein was ready for anything. “We rehearsed and role played so that we would be able to talk to visitors while keeping our defenses down and our personal views out of it.”

Corporations, community groups, schools, and government agencies joined in the conversation. According to Moses, the Pentagon used the exhibition for training purposes and the National Institutes of Health for research. The D.C. run met with such success, she continues, that it was held over for an additional three months during the summer so that international tourists could experience it. Back in Minnesota, Best Buy also opted to use the exhibition as a professional development tool. That was something the museum encouraged by establishing Talking Circles. Borrowed from Native American traditions and moderated by trained facilitators, the circles provided a space for groups to come together to talk openly—and listen. This type of involvement—ranging from corporate sponsorships to community outreach programs, legions of volunteers to school groups—continues to be a hallmark of the exhibition as it travels across the country. “ [The exhibition] is rich in science and very rich in humanity. You learn how powerfully and subtly perceptions of race play out.”

- Bryce Seidel, President and CEO of the Pacific Science Center“We saw it as a wonderful opportunity to help people,” says Bryce Seidel, president and CEO of the Pacific Science Center. During its three-month stay at the Seattle museum late last year, RACE brought in more than 108,000 visitors, including some 270 field-trip groups of area 5th to12th graders and hundreds of volunteers. “Museums are viewed by the public as being neutral,” he says, “so they’re great places for this kind of exhibit.”

RACE, Seidel continues, “is rich in science and very rich in humanity. You learn how powerfully and subtly perceptions of race play out.” Pittsburghers Speak UpWhat lessons will Pittsburgh learn? No one can say for sure, but Dina Clark, director of the YWCA Center for Race and Gender Equality, can’t wait to find out. Clark is looking to connect the city’s youth with museum staff. She plans to work with a corps of teen volunteers who will participate in a youth summit staged during the run of the exhibition. “Youth respond to their peers,” she says. “I want our volunteers to be ready to share and answer questions about the topic of race.”

Harris’ historic portraits and his subjects’ responses will be presented in a Community Voices Gallery alongside their contemporary counterparts. Visitors will also be invited to post their own responses.

From Clark’s perspective, the timing of the exhibition couldn’t be better. After hosting major events like the G-20 in 2009 and the One Young World Summit in 2012, the world has come to see Pittsburgh in a new light, and Pittsburghers have seen the world in their own backyard. She’s hoping the exhibition will inspire and leave a lasting impression on this city of neighborhoods. “There’s nothing wrong with being proud of your ethnicity, culture, and history,” Clark asserts, “but that shouldn’t be used to segregate. Don’t be fearful of the differences, appreciate them.” RACE: Are We So Different? is presented locally by EQT Foundation. Additional support is provided by The Pittsburgh Foundation, The Heinz Endowments, and Dominion Foundation.

|

|||||||||||||

Silver & Suede · The Tedious Intrigue of Art Conservation · Sun Struck · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Nicholas Chambers · Artistic License: The Science of Sculpture · Science & Nature: Nature as Classroom · About Town: Friends of the Forest · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |