|

||||||||||||||||||||

Andy Warhol, Silver Clouds [Warhol Museum Series], 1966/1994, © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.Halston, Dress, 1972, Ultrasuede, The Museum at FIT, Gift of Mrs. Sidney Merians |

Silver & Suede

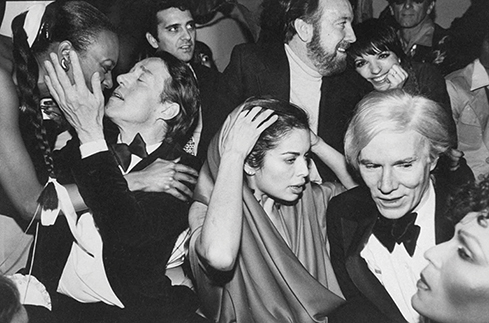

How the co-evolution of Andy Warhol and Roy Halston changed the face of American art, fashion, and celebrity. Roy Halston’s living room, grand in its spareness, contained minimal furniture. My life is now and modern, the fashion designer was known for saying. And so his three-story townhouse served as a rotating gallery for his vast collection of art. It was 1970s New York City and the likes of Liza Minnelli and Elizabeth Taylor would visit for dinner and gossip. With the fireplace roaring year-round, Halston served baked potatoes with caviar and a simple butter lettuce salad. After dinner, he might encourage impromptu fittings, making gifts of garments in silk and cashmere. The mezzanine wall was a certain kind of centerpiece. Stacked vertically in a series of three, portraits of the man himself accentuated the room’s height and spoke to the kooky and admiring relationship between Halston and the artist Andy Warhol. At the time, Warhol lived just a few blocks away on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. “Andy would walk down Lexington Avenue and come to play with Halston,” recalls Lesley Frowick, Halston’s niece, who lived and worked with the designer. “They’d hang out for dinner and drive off to an event in a limousine.” It was a moment particular to its time. Designers and artists, once relegated to the wings of runway shows and off-center corners of gallery openings, were becoming the ultimate celebrities. The emergence of disco and glamour in nightclubs placed a magnetic set of personalities at elbow’s length. Life “behind-thescenes” was more public than ever. Halston, young and handsome, was then nearing the apex of his career, one that would remake American fashion from the buttoned-up and heavily fussed to the streamlined attire of a modern working woman. Though his name is less recognizable than Warhol’s today, Halston’s influence on the world of fashion was broad, permanent, and not unlike Warhol’s on art. His structural one-piece garments were as easy to wear as they were luxurious to touch. And his ability to build an empire was an early example of the broad reach attained by celebrity moguls today. A new exhibition opening May 18 at The Andy Warhol Museum, Halston and Warhol: Silver and Suede, sets the lives and work of the two men side-by-side. Co-curated by Frowick and Nicholas Chambers, the Milton Fine Curator of Art at The Warhol, the show highlights the quirks of Halston and Warhol’s co-evolution, juxtaposing works of mutual inspiration and demonstrating, through photography and personal memorabilia, the broader social scene and intimate moments that defined how these two men came into themselves as artists. A Brush With JackieThough Halston and Warhol didn’t meet until the mid- 60s, their similar gravitation toward pop culture and creative expression is evident much earlier. “While they didn’t directly collaborate on a project together until the 1970s, there are fascinating parallels that can be drawn between the beginnings of their careers,” says Chambers.

Halston was born in Des Moines, Iowa, in 1932 to a modest family of Anglo-Saxon and Norwegian descent. Though they moved frequently to accommodate his father’s changing jobs, the family proved an early and stable supporter of Halston’s creative work. As young as age 9 he began designing hats out of straw, feathers, and household items, which his mother, sister, and cousins wore around the family farm or to church on Easter Sunday. Halston entered the fashion scene as a milliner, operating his own successful hat shop in Chicago before being lured to New York by French fashion designer Lilly Daché. About a year later he was named the chief millinery salon designer at luxury-goods department store Bergdorf Goodman. He developed a network of wealthy clients, but perhaps none so influential as one. In 1961, Jacqueline Kennedy wore his pillbox hat to her husband’s inauguration, after which Halston’s designs became a sensation. “Andy and Halston both came of age at the same time,” says Frowick, who is writing the first authorized biography of Halston. “Both of their fathers worked very hard. It was right after the Depression, so they came up knowing what a really hard work ethic was. In fact, they were workaholics.”

“We’ve secured for the show one of the pillbox hats [Halston] designed for Jackie Kennedy,” says Chambers. On loan from the JFK Library in Boston, the hat will appear alongside Warhol’s Jackie paintings from the museum’s collection. “It’s very much about creating juxtapositions between their works,” he notes, “and we start off by making that point via an icon of American culture.” Creative DialogueThe show pulls most of its works from three sources: The Warhol’s collection, the archive of Halston’s personal effects given to Frowick by her uncle, and the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York, which owns a vast collection of Halston garments. To complement the exhibition, The Warhol is publishing a richly visual 242-page catalogue, which includes commentary from a variety of voices.

Vivid glimpses into the lives of Halston and Warhol come from so many angles that the impressions overlap like collage. One particular highlight is an interview with Pat Cleveland, a member of a core group of Halston models called “Halstonettes.” When asked how fashion and art related to each other in the 1970s, she replies, “The people made the connection.” During the 1970s, both Warhol and Halston expanded their reach as creators. Warhol acquired a camera and began working regularly in film. He developed ideas for a soap opera—cast with some of Halston’s models—and a 10-episode program titled Fashion. He managed the band The Velvet Underground. Halston established a ready-to-wear line, designed his famous shirtdress in Ultrasuede (a machine-washable fabric that would become a trademark), and signed massive licensing deals, including lines for fragrances, cosmetics, eyewear, bedding, carpets, and swimwear—some of which he’d later promote in Warhol-designed advertising campaigns. Of the impulse to try new things, Warhol offers this explanation in his book America: “The Pop idea, after all, was that anybody could do anything, so naturally we were trying to do it all. Nobody wanted to stay in one category; we all wanted to branch out into every creative thing we could.” "They were a phenomenon. People wanted to be close to them and know what it was all about."

- Lesley Frowick, Halston's Niece

Mutually InspiredEach in their own way, Halston and Warhol had been pushing boundaries from the start, even though Halston’s early career was more self-censored. “He was working in an old-world sort of environment at Bergdorf, having to answer to the man,” says Frowick. “Warhol was a free man. Halston was not restrained, however, when he did his Coty Awards in 1972. Here he probably took some inspiration from Andy’s wild side.”

These patterned garments were a relative departure for the designer. “When you think of Halston, you really think of solids,” says Fred Dennis, senior curator of costumes at the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology and an expert on Halston style. But their simple structure is still classic Halston. “It’s that very clean line, almost the direct opposite of Haute Couture in Europe,” he notes. “Everything was over-the-head like a t-shirt.” Halston famously created his drapey silhouettes by flinging reams of fabric around models in his studio, strategically pinning material and stitching it together, sometimes with only one seam. It’s in this “paring down” effect that the exhibition brings to light one of Warhol and Halston’s most fundamental aesthetic overlaps. “During that time, everyone was sort of reductive,” says Dennis. “Warhol took a simple soup can and made it an art icon. He was abstracting down to the common denominators, and Halston was doing the same thing with clothing.” In addition to a diverse collection of works by Warhol—many once owned by Halston, including diamond dust silkscreens of Martha Graham, Mao Zedong, and Warhol’s beloved dollar signs—the show presents an assortment of personal items that Chambers finds especially compelling.

Though their professional partnership began to unravel in the 1980s (after Halston’s business was swept up in a larger corporate sale and ultimately taken from his control), their friendship continued up to Andy’s death in 1987. Soon after, Halston left New York for California. "I’m particularly interested in some of the photography and ephemera that relates to the relationship they had outside of the spotlight. it’s just totally infectious and wonderful."

- Nick Chambers, The Warhol's Milton Fine Curator of ArtDecades later, Frowick finds great personal meaning in the show. She was there to witness the quiet bond the two men shared in the spotlight: “They were both reserved,” she says. “You’d go to a party and there’d be all this commotion around these people. And then you’d go over and see Halston and Warhol just sitting there, not saying anything. They were a phenomenon. People wanted to be close to them and know what it was all about.” Halston and Warhol: Silver and Suede is all about inviting new audiences into both worlds—the very public, and what’s behind it. Most fundamentally, the show provides a dedicated space for the two men to continue their dialogue and create, as Frowick puts it, in one final collaboration.

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Unraveling Race · The Tedious Intrigue of Art Conservation · Sun Struck · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Nicholas Chambers · Artistic License: The Science of Sculpture · Science & Nature: Nature as Classroom · About Town: Friends of the Forest · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |