|

||||||||||||||||

Photos: Joshua Franzos |

The Tedious Intrigue of Art Conservation

How Carnegie Museum of Art conservators expose fakes, restore past glory, and play doctor to every art form imaginable. The portrait of a 16th-century society lady stored in the basement of Carnegie Museum of Art stood out for all the wrong reasons. According to the museum’s records, it was a portrait of the famous beauty Eleanor of Toledo by the great 16th-century painter Bronzino. It’s awful, thought Louise Lippincott, curator of fine arts, as she spied it hanging next to other Renaissance paintings.

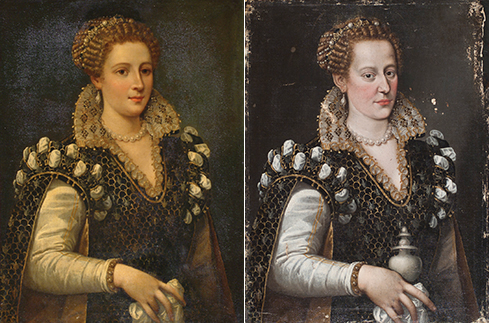

The woman’s ornate dress with its stifflace collar was historically accurate, but her face looked more like a 1920s silent film star than a 16th-century aristocrat. And that was only part of what seemed amiss. Before deciding whether or not to recommend deaccessioning it from the museum’s collection, Lippincott brought it upstairs and had it evaluated by Ellen Baxter, the museum’s chief conservator. Baxter examined the crack patterns on the paint surface and immediately knew something was off. Was it a fake? So began an art investigation complete with a trip to the x-ray room, mysteries concealed in layers of paint, and a wild ride through Florentine history. The results of this artistic sleuthing will be on display in the exhibition Faked, Forgotten, Found: Five Renaissance Paintings Investigated, opening June 28. The show will not only tap into everyone’s fascination with fakes and forgeries, but will showcase the museum’s ongoing conservation and research efforts through an intriguing mix of science and art. This detective work is part of a multi-year reevaluation of the museum’s collection as it undertakes the reinstallation of its permanent galleries. From Renaissance paintings to contemporary art, from sculpture to film, and everything in between, the museum is constantly conserving its treasures. Baxter’s rare mix of left- and rightbrained talent is illustrated by her curriculum vitae: a bachelor’s degree in art history with minors in chemistry and physics from Oakland University in Michigan and a master’s degree in art conservation from Queens University in Ontario. “She paints as well as an MFA,” Lippincott says. The skilled conservator looks at paintings differently than other people, too—not as flat, static objects, but as three-dimensional compositions layered like lasagna. The minute she saw the oil painting purported to be of Eleanor of Toledo, wife of Cosimo de´Medici, the first Grand Duke of Florence, Baxter knew something wasn’t quite right. The face was too blandly pretty, “like a Victorian cookie tin box lid,” she says. Upon examining the back of the painting, she identified—thanks to a trusty Google search—the stamp of Francis Leedham, who worked at the National Portrait Gallery in London in the mid-1800s as a “reliner,” transfering paintings from a wood panel to canvas mount. The painstaking process involves scraping and sanding away the panel from back to front and then gluing the painted surface layer to a new canvas.

“From a distance, she will look magnificent. But up close, an expert will be able to tell modern retouches from the original in keeping with ethical conservation practices.”

- Louise Lippincott, Curator of Fine Arts“That’s why the crack patterns didn’t make sense,” Baxter says. Paintings on canvas should have relatively large cracks, she explains, but the cracks she was seeing were too small, and more typical of a panel painting. Combining this observation with her knowledge of Francis Leedham’s work, she realized that the portrait and its characteristic cracks had been transferred and repainted to make it more saleable for 19th-century buyers—some 300 years after it was first painted around 1570. To test that theory, Baxter loaded the painting into her car and drove to the Monroeville Imaging Center. Surrounded by patients with broken bones and suspected gallstones, the conservator presented her subject to the technician. When she peered at the x-rayed image, she immediately saw newer layers of paint covering the woman’s face and hand. Whoa, she thought. Something is under here. Let’s see what’s left.

After experimenting with chemicals of varying solubility, Baxter removed layers of dirty varnish as well as some of the newer paint from the woman’s face and wrists, all the while taking great pains to conserve the original paint underneath. As she dabbed at the canvas, the woman’s features transformed from cookie-cutter dainty to reveal a longer nose, jowls, and a high forehead with the hairline plucked according to 16th-century fashion. The original rendition also revealed the woman holding an urn similar to the one that Mary Magdalene used to anoint Jesus’ feet. Then came a big break. Poring through Florentine art history books, Lippincott tracked down a copy of the painting, commissioned by the Medici family, which had been sent to Vienna in the 1580s and was still there. The inscription on it identified the woman not as Eleanor of Toledo but as her spirited and scandalous daughter, Isabella de´Medici.

What's In a Name?An intellectual who spoke many languages and entertained in a salon, Isabella, as the museum sleuths soon learned, was the favorite of her father, Grand Duke Cosimo. She married Paolo Orsini at age 16, a union so unhappy that Isabella remained in Florence while her husband lived in Rome. Isabella brazenly took lovers, including her husband’s cousin, and she got away with it under her father’s protection. But when her father died and her disapproving brother Ferdinando took over, Isabella met a terrible fate. Her husband and brother conspired to strangle her in 1576. Lippincott and Baxter believe that Isabella posed for the portrait and asked the artist to add the urn later on in a feeble attempt to rehabilitate her image from fallen woman to a pious one. The urn sits shallowly in her hand and its perspective isn’t quite right, which suggests it wasn’t part of the original composition. “This is literally the bad girl seeing the light,” Lippincott says. After scraping off old paint using a microscope and scalpel, Baxter will dab on new paint with a surgeon’s precision, restoring Isabella’s grandeur. “From a distance, she will look magnificent,” says Lippincott. “But up close, an expert will be able to tell modern retouches from the original in keeping with ethical conservation practices.” The painter, one of a half dozen artists employed by the Medici court, is still unknown because the work is unsigned, a common occurrence during a time when most artists were illiterate. So is the painting a fake? Absolutely not, says Lippincott. It’s an authentic 16th-century painting that was later overpainted, probably to make it more appealing to collectors. “The polite way of saying it is that it was so heavily overpainted that we mistook it for a fake, fabricated to deceive.” Joining the newly discovered portrait of Isabella in the Faked, Forgotten, Found exhibition is a painting by Francesco Francia titled Madonna and Child with Angel. It’s authentic but less well-known than the convincing fake at the National Gallery in London. A controversy unfolded when the one now owned by Carnegie Museum of Art hit the art market in the 1950s. “We ended up doing the Snoopy dance, because we have the real one!”

- Ellen Baxter, Chief Conservator on Madonna and Child With Angel

Lippincott explains that the National Gallery’s painting was commissioned to help prevent a 19th-century family inheritance dispute. “Both sides of the family thought their version was the original painting,” she says. “Everyone took them at their word. The problem arises when the paintings hit the art market.” Though the National Gallery officials believed for years that they had the original, last year conservators traveled to Carnegie Museum of Art to test a theory that the London painting was modeled on the one in Pittsburgh. Their meticulous research will be showcased in the Pittsburgh exhibition. “We ended up doing the Snoopy dance, because we have the real one!” says Baxter.

Chasing the CluesBaxter leads a four-person conservation team that touches every part of the museum’s vast collections. She specializes in paintings, while Michael Belman, the museum’s objects conservator, works his special blend of artmeets- science magic on three-dimensional art—from a fragile papier-mâché piano ambitiously crafted in 1867 for a world’s fair to a modern sculpture made from stainlesssteel tubing. Together with a technician/departmental assistant and a new researcher hired specifically for time-based media, they help care for everything from centuries-old masterpieces to contemporary art created with new materials. Lippincott likens preserving old paintings to archaeologists digging for clues about artists who are long dead: “The only way we can find what is going on is through physical evidence.” By contrast, caretakers of the museum’s modern and contemporary collections collaborate mostly with living artists who work in new and sometimes difficult materials that pose their own distinct set of challenges. Consider the anticoagulated animal blood on 42 panels created by Tim Rollins for the 1991 Carnegie International. This past summer, as part of the reinstallation of the museum’s permanent modern and contemporary galleries, the work was to be rehung with others from Internationals past as a first phase of the 2013 Carnegie International. Upon unpacking it from storage, it was discovered that the blood was cracking and flaking. To preserve the fragile ingredients, Baxter consulted with a physician and experimented with various consolidants. She finally settled on a saline solution to humidify the flakes and a Japanese seaweed and other adhesives to reattach them. She then inpainted, or filled in, the lost pigment. “It looks quite good,” she admits. By contrast, some art is intended to age over time. An installation in the museum’s permanent collection by contemporary artist Gedi Sibony features bird cages, wires, cardboard, foam core, and other fragile materials draped from the walls and ceilings. Dan Byers, the museum’s Richard Armstrong Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, was able to ask the artist if he wanted the plastic sheets to yellow naturally or if they should be replaced with clear sheets over time. Sibony opted for natural aging. Some contemporary art made of organic materials, or beeswax and latex in the case of Paul Thek’s famous “meat pieces”—is deliberately designed to have a short shelf life or to require constant upkeep. In considering such acquisitions, the museum has to weigh the maintenance costs of the work against its merit. “There is a calculation that occurs,” Byers says. “There are works that may be far too expensive to maintain over time. But if it was artwork that was paradigm- shifting, we would figure out a way to live with it.”

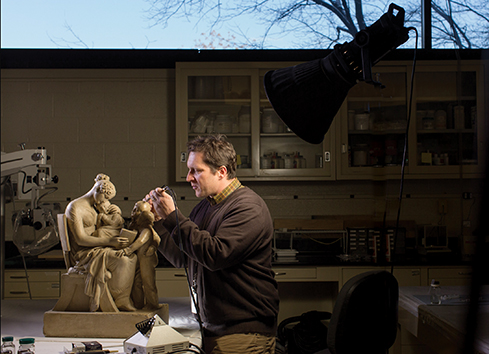

Just as Byers asks artists about their conservation wishes, Philip Leers, a senior research associate hired by the museum in 2011 to study its time-based media collection— which includes film, video, audio, and computer-based art—follows the artist’s lead. Much of the media Leers and a small team of collaborators from the Museum of Art and The Andy Warhol Museum oversees is digital, but a chunk of the collection remains on film. While it’s a relatively fragile medium, the museum does its best to honor filmmakers’ wishes, when necessary contacting artists before digitizing their work for preservation purposes. “There are filmmakers who feel very strongly that their work should only be seen on film,” says Leers, noting that the museum also doesn’t always have the right to digitize work and could instead be required to purchase a digital copy from the artist or a distributor. The most authentic way to conserve film is to create a negative through a photochemical process, Leers explains, but at tens of thousands of dollars it’s usually prohibitively expensive. Museum curators believe it’s well worth the expense to reproduce 10 reels of film by the famed African American photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris, whose vast photographic archive, a treasure of the museum’s collection, is one of the most detailed and intimate records of the black urban experience known today. Last year, the films were deemed one of the 10 top endangered artifacts in Pennsylvania by the Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts. “This is a special collection,” says Leers. “We have the only copy. We have footage of the Negro League baseball games, footage of a family vacation. We’re not thinking of Teenie as a great filmmaker, per se, but as a great photographer who films portraits of people that are very reminiscent of his photographs. Many are home movies he made for his family and his community. It adds depth and context to his photographs and gives us another glimpse into his life.” Restoring the GloryWhile Leers preserves film and video, objects conservator Michael Belman treats works made out of bronze and marble. Belman recently completed a quite daunting project: restoring the magnificent glow to the Noble Quartet, the bronzes of Shakespeare, Michelangelo, Bach, and Galileo that keep watch over the Forbes Avenue façade of the original Oakland museums. They embody the virtues of Andrew Carnegie’s gift to the city: science, literature, art, and music. The quartet was restored in 1987 by an outside conservation company, but decades later, streaked and watermarked, they were due for a touch-up. So after washing the bronzes, Belman applied a brown-tinted wax blend containing antioxidants. Using propane torches, he and an assistant heated the hulking figures in square-foot sections, applying the melting wax mixture onto the surface. Once the treatment cooled, they buffed those bronzes—for more than a month and a half—to a shine.

“The overpaint proved extremely challenging to remove and I wound up throwing everything in the book at this.”

- Michael Belman, Objects ConservatorBelman, who studied sculpture at the Tyler School of Art at Temple University before receiving his master’s in art conservation at Queen’s University in Ontario, says his fine arts background gives him a step up. “You have the familiarity with the objects that’s tough to gain on the fly.” That understanding of sculpture comes in handy as he undertakes his current challenge: restoration of a painted plaster cast by British Neoclassical sculptor John Flaxman. Maternal Tenderness: Memorial to Lady Fitzharris, an 1816 sculpture that depicts a mother reading to her three children, is a recent museum acquisition stewarded by Lippincott. When it arrived at the museum after almost 200 years in London’s smoky environment, the original painted plaster surface had been covered with successive layers of paint and grime that obscured the delicacy of Flaxman’s modeling. In order to try and return it to its past glory, Belman first removed very small samples, embedded them in resin, and cut them to reveal a cross-section of layers: original color, several layers of overpaint, and dirt. Following three months of meticulously testing various methods of overpaint removal, Belman devised a successful strategy of heating the overpaint gently with a heat pencil and removing it mechanically with a scalpel. The process—which may take another three to six months to complete—was daunting. “The overpaint proved extremely challenging to remove and I wound up throwing everything in the book at this,” says Belman. “Generally we find that sculpture was overpainted for a reason and it can be a can of worms. You may just find a severely degraded surface underneath that looks much worse than before you started.” In some ways, an art conservator is like a doctor for fine art, whether it be a Florentine painting, a VHS video from the 1970s, or a sculpture from the current Carnegie International. As Lippincott puts it, “All of this is like elective surgery. First do no harm. Then preserve as much of the original as possible.”

|

|||||||||||||||

Unraveling Race · Silver & Suede · Sun Struck · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Nicholas Chambers · Artistic License: The Science of Sculpture · Science & Nature: Nature as Classroom · About Town: Friends of the Forest · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |