|

||||||||||||||

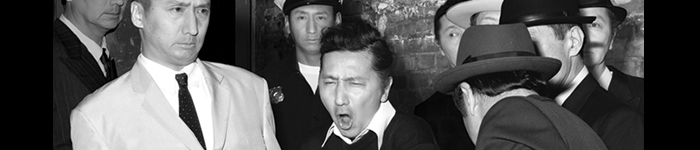

Yasumasa Morimura, A Requiem: Oswald, 1963, 2006, Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York |

The Stand-in

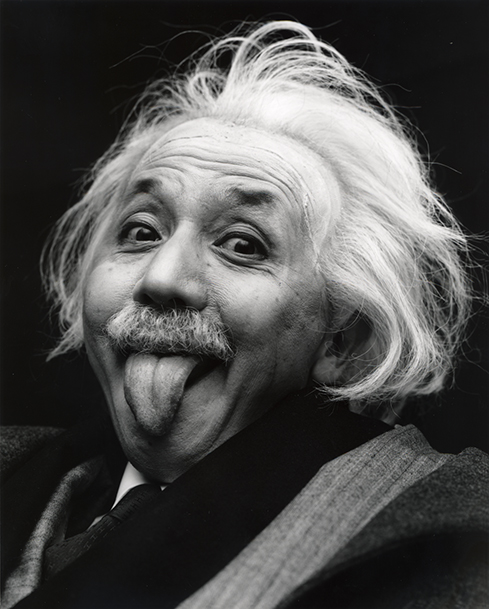

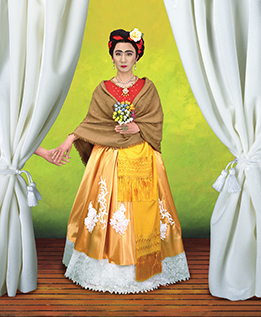

Japanese artist Yasumasa Morimura literally inserts himself into art history through his photographs, claiming a space for outsiders and making “art that is fun.” By Barbara Klein Yasumasa Morimura is many things: photographer, videographer, performer, designer, singer-songwriter, and author. Along the way, he has become many people: Albert Einstein, Frida Kahlo, Lee Harvey Oswald, and Jack Ruby, not to mention the Mona Lisa. Best known as an appropriation artist, the 61-year-old Osaka native has made an international name for himself by taking classic works of art, iconic images, and celebrity portraits and painstakingly reconstructing them as new photographs. His versions all share a singular identifying feature, a twist that prompts viewers to do a double take. Morimura assumes the identity—the starring role and, at times, the entire supporting cast—in these well-known and easily recognizable paintings and photographs. “I don’t do my painting on a canvas, I do my painting on my face,” he has said. “We may study such photos and find much of interest, but I prefer to bring them back to life as things of the present. A bit like reconstituting freeze-dried tofu and serving it up again to eat now.”

According to Eric Shiner, director of The Andy Warhol Museum, “Morimura is an expert at redefining, deconstructing, and representing culture as we know it. He inserts himself in our collective consciousness, and quite literally says that Western art history and Western film have a global impact.” There’s also a bit of ego involved in the process, adds Shiner. “He’s asking the question, ‘If I can replicate this in my own way, am I as good as the original?’” An expert in contemporary Japanese art and architecture, Shiner certainly knows his subject; he did his master’s thesis on Morimura. Is it any wonder, then, that bringing the man and his art to The Warhol has been at the top of Shiner’s to-do list for quite a while? But the timing just never seemed right—until now. It’s no coincidence that as Carnegie Museum of Art opens the 2013 Carnegie International on October 5, the very next day The Warhol will open the first-ever retrospective of Morimura’s work in the United States. The exhibition will run through January 12, 2014.

“Morimura is one of the most influential photographers in the world,” says Nicholas Chambers, The Warhol’s Milton Fine Curator of Art. “We are quite evangelical about his work.” The Entertainer

As far as the artist is concerned, the game is not all that complicated. “Art is basically entertainment,” he said in a 1999 issue of Fine Art Photography. “Even Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci were entertainers. In that way, I am an entertainer and want to make art that is fun.” He also wants to make art that speaks to its particular time and place in the grand scheme of things. “The shift now is not so much from art history to history, as it is from working with painting to working with photography as a source material,” said Morimura. “When I began considering the 20th century, there were plenty of fabulous paintings to work with, but the medium that I felt most effectively manifests the age is photography.” He embarked on his artistic journey after graduating from Kyoto City University of Arts in 1978. By the mid-1980s, he garnered attention when he unveiled his reassembled version of Van Gogh’s Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear. In what would become Morimura’s signature style, he meticulously staged the scene—complete with costuming, makeup that mimicked the brushstrokes, backdrop, and performance— and took a photograph that, in essence, created a new original. At first glance, there seems to be little difference between the two images. Then the subtle changes—the red of the lips, the tilt of the pipe—become apparent. And then the real kicker: an Asian man, Morimura himself, sitting in for Van Gogh. “Morimura tries the images on, in the sense of trying on clothing,” Chambers says. “He tries to get under the skin, under the surface.” In doing so, he adds, “Morimura presents the audience with an opportunity to reevaluate a particular work of art, to look at it with fresh eyes.” “Morimura tries the images on, in the sense of trying on clothing. He tries to get under the skin, under the surface. [He] presents the audience with an opportunity to reevaluate a particular work of art, to look at it with fresh eyes.”

- Nicholas Chambers, The Warhol's Milton Fine Curator of ArtAs it turns out, that first stand-in launched a series of works dubbed Daughter of Art History in which Morimura took on the masters, including Rembrandt, Goya, and Manet. On the heels of that adventure, he began an extensive exploration of renowned Mexican artist Kahlo. He once described her work as “a fierce and intense manifestation of human sentiments and universal themes, such as joy, anger, sorrow, happiness, beauty, life, and love.” In his An Inner Dialogue with Frida Kahlo series, Morimura layers his concept of the selfportrait with her own self-portraits. The resulting experience is unique, yet familiar. The Warhol WayThe familiar response to seeing Morimura’s work is a sense of disorientation, a kind of dizziness that leaves viewers musing about the push-pull relationship between masculinity and femininity, the past and present, praise and parody, East and West, painting and photography.

His Actresses series has found its own wiggle room between traditional Japanese Kabuki and Noh (puppet) theater and the ever-burgeoning digital realm. In that mid- 1990s assemblage, Morimura plays the role of glamorous leading lady—for example, Greta Garbo, Ingrid Bergman, Brigitte Bardot, Audrey Hepburn, and Marilyn Monroe. He then expands his palette to include more recent celebrity superstars like Michael Jackson and Madonna. Sound like anyone we know? Morimura has, in fact, described himself as Andy Warhol’s “conceptual son.” “Warhol’s own fixation with popular culture paved the way for artists like Morimura,” Shiner says. “He is paying homage to Warhol.” Despite a pronounced interest in the fluidity of sexuality and gender in his work, Morimura is much more of an enigma, not explicitly discussing his own sexuality. He has said, “In Japan we have a phrase to describe something weird and hard to pin down: ‘the thing one can’t determine if it belongs to the ocean or to the mountain.’ That’s me.” Chambers says, “Both artists have the ability to hone in on images that have the most impact.” It should come as no surprise then that Morimura tries Andy on for size in his The Story of M’s Self-Portraits. “There is a theatrical quality to these images,” Chambers says of the series. “Modest in scale, they are more concerned with the figure than with elaborate sets, and have the effect of emphasizing the performative nature of Morimura’s project.” About 50 of them will stand front and center as part of the exhibition at The Warhol. “They will travel to Pittsburgh from Japan, where they have been on loan from the artist to the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art. Like several other works in the exhibition, this group of photographs has never before been seen in the U.S.” Requiem to the PastSomething else that has never, or very rarely, been seen is Morimura acting as curator. Together, Morimura and Chambers are combing through The Warhol’s vast archives and adding artworks to the collection galleries that resonate with Morimura’s own work. No doubt, Chambers says, “Morimura will bring a fresh perspective to our collection.”That’s likely what the brain power behind the Yokohama Triennale, an international survey of contemporary art, had in mind recently when it named Morimura the artistic director of its fifth exhibition, which is set to open next August. Never one to shy away from multitasking, for the past several years Morimura has also been shining a light on his project Requiem for the XX Century. In this series, he focuses on photojournalism: famous snapshots in time, such as the 1963 Ruby shooting of Oswald in the aftermath of the Kennedy assassination and the 1968 execution on the streets of Saigon during the Vietnam War; famed dictators Mao, Lenin, and Hitler as portrayed by Charlie Chaplain; beloved activists including Gandhi and Che Guevara; and artists such as Picasso, Salvador Dali, and Yukio Mishima, the Japanese author whose failed coup attempt in 1970 ended with his ritualistic suicide. Of course, Morimura remains the face in front of the camera. But given the seriousness of much of the subject matter in Requiem, his usual sense of playfulness is not as palpable. “Instead of building the future on a denial of the past, we need to think in the present about how we can inherit what went before,” he’s said about the work. “I decided to approach history as the glue that would bind the past with the future. “I don’t do my painting on a canvas, I do my painting on my face. We may study such photos and find much of interest, but I prefer to bring them back to life as things of the present.”

- Yasumasu Morimura“A requiem is an expression of respect for the people, times, and thoughts that have gone. It is a ceremony to preserve those things in our memories. My requiems are a kind of testimony: ‘I will not forget you.’” Shiner believes Pittsburgh won’t soon forget Morimura. “I think people will love his work,” he says. “People here share a fascination with glamour, and will appreciate the humor in his work—people in Pittsburgh like things outside the box.” And Shiner feels confident that Morimura will love Pittsburgh as well. “He was born in Osaka, so I think he’ll feel a strong connection to the city’s industrial heritage, and he’ll go completely bonkers with all the museums.” Chances are good, though, that Morimura will keep a low profile while he’s in town. Shiner adds, “You would never expect someone who is so flamboyant in his artwork to be so shy.”

|

|||||||||||||

2013 Carnegie International · Artist as Activist · History Redux · Artists In Their Own Words · Frozen In Time · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Lauren Talotta · Science & Nature: Cultural Craftsman · About Town: Wild by Design · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |