|

||

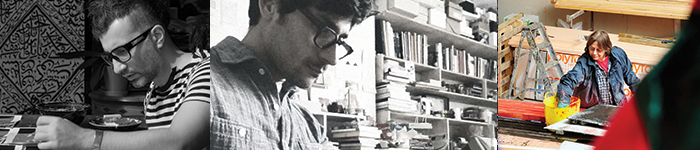

Left: Photo: Maziar SadrRight: Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Thierry Bal

|

Left to right: Rokni Haerizadeh, Gabriel Sierra, and Phyllida Barlow

Artists in Their Own Words ROKNI HAERIZADEH speaks to the moment.Iranian artist Rokni Haerizadeh works in paint and video animation to create art that investigates world cultures while often adopting a satirical tone, depicting ritual in caricature. Haerizadeh and his artist brother, Ramin, chose not to return home to Tehran after a 2009 trip to Paris, fearing imprisonment after governmental officials seized their works from a collector’s home. The brothers now live and operate a studio in Dubai. The 2013 Carnegie International is the U.S. museum premiere of Haerizadeh’s work. How have you seen your work change since leaving Tehran? I have always been intrigued by social gatherings and rituals, violence, and decadence. Now the element of time has become important to me and it has taken my paintings in a new direction. A painting is usually received by the viewer and by the critic as a fixed and static object, with the entire process of generating the work far removed from the final piece. It’s important for me to add this element of “time,” to slow down the process and to make that process visible. In this way, the painting unfolds before your eyes and transforms gradually. In time-based works like Reign of Winter (an animated film that will be screened at the International), I paint each image frame by frame, creating a “pulse.” Figures literally vibrate and transform as the work progresses. In this way it exceeds the two-dimensional boundaries of works on canvas and erupts out of that paradigm into something grotesque and new. “Being” is also becoming important to me. Through movement, transmitting a pulse of our times is important. I feel the presence of pulse, and it is important that my paintings pulsate with the presence of a being. Your work often comments on the cultural and political traditions of Iran, yet Reign of Winter takes on the subject of British royal weddings. What piqued this interest? I don’t intend to comment on any specific cultural and political traditions. I declare the iconic moments of our times, whether they’re in Iran or elsewhere. I am interested in how media functions to influence our perception of our world. There are weddings, wars, and protests everywhere—in all cases I’m interested in their representation and not simply their content. The royal wedding, per say, is not what’s important. It’s the representation of the royal wedding by the media that’s important to me. You can also think of this work as my self-invitation to the wedding. How is visual art an effective way to create commentary—either on a particular subject or on culture more broadly? I think an artist should discover and express the essence of his times. He should be able to observe his surrounding with a keen eye and suck the marrow out of what he observes. If he can do this well, then his work becomes more than just a critical view—it becomes a sort of prophecy, an anticipation of what’s to come. The process of getting to this point takes place in the mind—a series of things happens simultaneously during this process: from observing, to assessing, wondering, and pondering. The creative process brings all these factors together to finally reach a state that is beyond simple criticism. It is in the nature of art to depict reality and that, by itself, is critical. GABRIEL SIERRA delivers the royal treatment.Gabriel Sierra, an emerging artist from Bogotá, Colombia, likes to shake up his surroundings by physically transforming architectural spaces— moving or cutting away pieces of walls, re-compartmentalizing rooms. Such interventions, he says, are his way of scrambling our sense of self within a space. For the 2013 Carnegie International, Sierra is aiming big by using color to transform one of the Museum of Art’s most iconic spaces: He is painting the walls of the Hall of Architecture purple. You first went to school to study architecture and industrial design. How has this background informed your art? The main function of architecture is to create buildings and spaces. Objects work as extensions of the body, to assist in different everyday purposes. But the function of art is a mystery. It’s in the subjective mind of the artist and his moment in time. For sure, I’m interested in making new things, but at the same time, I’m interested in objects and places that belong to history. Perhaps my intention is to experiment with moments and sensations that are simultaneously part of the past, present, and future in our subconscious. As well, I try to ask myself, what is the true responsibility of an artist? You explore time through architecture. What drew you to the Hall of Architecture? What I find interesting and particular to the Hall of Architecture is that the meaning and purpose of the room remains the same as when it first opened. It’s one of the oldest spaces in the world created specifically for the display of ancient architectural replicas. Seeing all of the architectural fragments was an overwhelming experience; the scale, the form, the gravity of the objects. I started thinking about how I could connect them. All of these elements come from lost civilizations that were very aware of the relation between the cosmos, nature, and knowledge. I’m interested in how an observer confronts the size of his body in relation to the scale of these architectural fragments. Your work often disrupts physical space by playing with lines, surfaces, and shapes. But your project for the International relies heavily on color. Why? When I decide to use color, it’s because I don’t want to build something disruptive to erase or neutralize the history of the room. The tradition of sculpture is related to the mysticism that uses geometry as a tool of translation. On the other hand, the museum is a kind of foreboding thing. I know this is one of the most important places in the Carnegie, yet maybe not too many people are interested in this kind of thing. So I wanted to bring back a little life to the room by changing the color, perhaps to invoke an element that belongs to the past, in abstract form. Why did you choose purple? I wanted to make a kind of bridge to connect the past and present. The color purple, in Gothic architecture or medieval history, was more of a concept than a color. The formula to prepare purple disappeared, so people started making it in their own ways. But in the end, the meaning was the same: It was sacred, royal, and had the material quality of velvet. Mystics, like the Indian yogis, saw purple during revelations, associating it with the saints. But they could not describe exactly the purple that it is. I think purple is much more of a sensation than it is a color. The phenomenology of the purple will be altered with the changing light [from the skylights]. It’s an experiment. Color is playing the game of container or background, to frame the casts. The experience of the exhibition is more than the color, it’s the room. It’s how I switch up the color of the walls in order to affect all of the things inside the room. PHYLLIDA BARLOW wants you to keep on walking.For 40-plus years, Phyllida Barlow made an indelible mark on British sculpture as a teacher, counting Rachel Whiteread and Tacita Dean among her now-famous students. But Barlow’s own massive, “anti-monumental” works flew largely under the radar of the international art world until five years ago, when the career of the 69-year-old artist hit full stride. For the Carnegie International, Barlow and her small team of assistants take on the busy front plaza of Carnegie Museum of Art, creating a rebellious, fence-like structure that will snake from the street into the museum. What do you mean when you describe your work as “anti-monumental”? I don’t see my work as big. I know it is. But everything is usually done in relation to what I can reach or what is within the reach of my body in the initial stages. There’s a sense of intimacy about the components that I want to retain. These components are in a way the opposite of the factory-made object. Each is individual, even though the instructions are generalized for the whole lot. That for me means that they’re not aspiring to be anything more than what they are. Not aspiring to reach for a grand emotion or a grand sense of memorial or respect; in fact, quite the opposite. They’re more to do with the everyday, the stumbling upon the everyday and then giving that a new existence in the form of something that is very much a large experience. You often use repurposed materials. What’s in the mix this time? There’s something ambiguous, I hope, about the mixture of materials. At one point they’re unforgiving materials, weathered timber, wire mesh, and cement. And then this kind of rather festive, you could also say frivolous, ribbons. There’s no fixed moment in time this sculpture is representing. It could be something is over, done and dusted, or it could be that it’s half-finished or something is just about to begin. I hope it has a sense of aliveness in that way. How did you approach a space that contains so many competing elements, including two other sculptures and a play structure? I wanted to dissect the space very boldly with a structure that would be very uncompromising physically, but would sort of reciprocate in a very different way than the [Richard] Serra. I think the structure I’ve made is completely absurd; it sort of doesn’t quite make sense. I think I’ve tried to make something with a syntax that is very bold in that it’s a long, fence-like structure, but it’s got these strange kinds of lumps on it and also ribbons attached to it. In a way it’s a very simple work, but it consists of 1,400 sections, so there’s a lot of labor involved in it. It’s a barrier, so people will have to kind of negotiate it, which is what I think you expect in an art museum, but maybe not so much on the street. Although there are hundreds of barriers on the street, hundreds of things you have to negotiate, they’re usually very official. They have a sort of official status telling you to do something or they’re safety factors, whereas this thing in a way is reneging on all of that, which I suppose is a risk of it just being a nuisance [laughing]. But, then, is the Serra a nuisance? I think we have to ask ourselves these things about sculpture. Your sculpture will in a way open the exhibition. Did this affect how you approached it? With such an incredibly exposed site, I was thinking about the human traffic and that they would be on the move—and that, in a way, maybe it wouldn’t be of great importance for the human traffic to stop and look. But more, how do you make a sculpture that’s a sculpture that you walk past? I was quite interested in the idea that a sculpture isn’t something you necessarily take time over or peruse, but it is more like a timebased sequence of these posts; something that you walk along and beside and maybe glance at, or it captures your attention but isn’t necessarily something you have to stand near and study. Which is a slightly odd idea, but one that fascinates me in the sense that the idea of looking at something quickly is actually, to me, quite intriguing. What do you remember, what do you capture from looking at something quickly rather than browsing it slowly and intently, which is the demand of a lot of art. But I’ve gone down quite a different route. This will be a sculpture that you experience when you’re actually on the move. In the way that maybe when you’re on a walk and you go past a field, there’s an overall sensation, or as the weather comes along, it takes you off your feet. You’re not concerned with detail; you’re concerned with something about the bigger experience.

|

|

2013 Carnegie International · Artist as Activist · History Redux · Frozen In Time · The Stand-In · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Lauren Talotta · Science & Nature: Cultural Craftsman · About Town: Wild by Design · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |