Fall 2013

Fall 2013|

“If you’re looking to make something bigger, faster, or stronger, chances are you’ll find the answer in nature.”

- Mike Hennessy, Program Developer at the Science Center

|

Wild by Design

In a new partnership with the Pittsburgh Zoo, the Science Center helps kids explore how animal adaptations—field tested in nature over millions of years— inspire technological breakthroughs.For his first trick, Mike Hennessy launches a plush turkey vulture over the heads of the kids seated in front of him. The kids shriek and wave their arms wildly. “Encore, encore,” one boy yells. As if on cue, Hennessy shoots two more toy birds out of an air compressor, and the laughter inside Bayer Science Stage at Carnegie Science Center crescendos into a giddy frenzy.

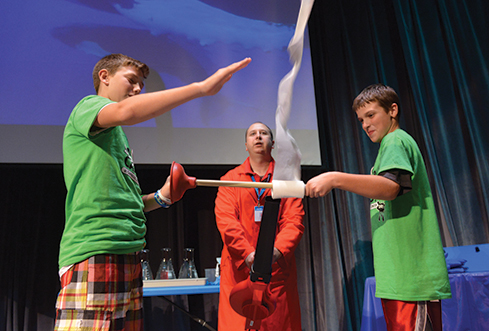

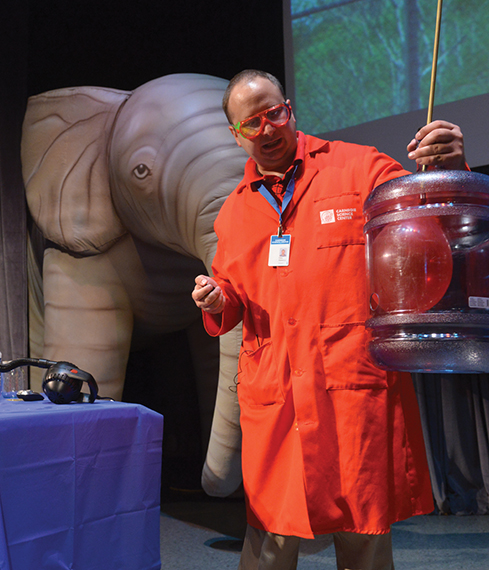

Making kids laugh isn’t the only reason Hennessy propels stuffed animals, although that’s certainly a perk of his job as program developer at the Science Center. More importantly, he’s helping curious minds grasp and enjoy science, in this case by illustrating a scientific principle key to the Wright Brothers’ pioneering aircraft. Back in 1903, Hennessy tells the crowd, the Wright Brothers had a problem. Their early planes crashed to the ground. Then one of the brothers noticed a turkey vulture, in preparing to take flight, adjust its feathers. That observation gave the famous duo the brilliant idea to build an airplane with adjustable wings, which helped keep it aloft. “If you’re looking to make something bigger, faster, or stronger, chances are you’ll find the answer in nature,” says Hennessy. That’s the take-home message of Wild by Design: Innovations from A to Zoo, a 45-minute live, hands-on science show debuting this fall in classrooms around the region to show students how technological advances often mimic nature. This August afternoon, the show, scripted and created by Hennessy and team, is being previewed for elementary and middle school-aged kids attending Science Center summer camps. The bird-flinging, barrel-booming, sudsspilling show is part of Science on the Road, the Science Center’s outreach program. Wild by Design is the fifth Science on the Road program supported by PPG Industries and the first to involve a partnership between the Science Center and Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG Aquarium, the local experts on all things wild-animal. The show takes students on a virtual trip to both the zoo and the science lab with videos that demonstrate human problems and their animal solutions. Interviews with real-world chemists, animal trainers, and robotics engineers introduce students to career possibilities in science and immerse them in the design process. In one segment, Sarah Topper, a chemist at PPG, says she’s in search of a new type of robot to spray paint a car, something flexible enough to get into its many nooks and crannies. Enter Willie Theison, the zoo’s lead elephant keeper, who appears on screen with Zuri, a teenage elephant with a whopping 40,000 muscles in its trunk that lend it the flexibility of a Slinky. The elephant’s unique anatomy, Theison explains, inspired a German robot maker to create a trunk-like arm that could paint cars easily.

But it’s not all show-and-tell. A handful of kids are called on stage and asked to stand next to a large inflatable elephant while dangling a Slinky to study its mechanics. They watch a slow-motion video of a Slinky falling six stories from the top of PPG Building Four, in downtown Pittsburgh. The kids marvel at how the top of the Slinky falls first, and it’s only when the top “catches up to” the bottom that the whole Slinky drops, due to the interplay of gravity and tension at work. Next up is Hennessy’s favorite animal innovation—the bumps on the fins of humpback whales that help them flow quickly through the ocean. Engineers put similar bumps on the blades of wind turbines, he explains, to help them rotate even in light winds. Smaller textured blades also help power computers. To illustrate this concept, Hennessy flips the switch on a powerful leaf blower, unfurling a roll of toilet paper onto the nowscreaming kids, all of whom are reaching out for a piece of the white streamer. Introducing Bernoulli’s principle, he explains that air goes over the top of a curved surface with more speed, and beneath it with more pressure, lifting it upwards. The concept is not lost on the kids. “I liked learning how you use animal features to make wind turbines go faster,” says 11-year-old Erick Ilkhanipour. The grand finale ends with a big bang, thanks to the humble pinecone. The cones hold their seeds for decades, Hennessy explains, but when there’s a forest fire the heat melts the wax inside the cones, eventually causing them to break open. The seeds that are released help rejuvenate the forest. “It’s like Jiffy Pop,” says Hennessy of the time-release mechanism. Scientists use the same principle on heat-activated fire sprinklers. To drive the lesson home, Hennessy places foam pinecones on top of a plastic trash can filled with hot water. He then adds liquid nitrogen to mimic the effect of wax inside the cone. Slowly the pressure builds until the top pops off the trash can with a loud bang, knocking the pinecones to the ground. “I liked the explosion,” says 8-year-old Nyla McGinnis. “It was a really loud boom. I learned that animals help make technology.” She also likes Hennessy. “He’s funny,” she says, grinning widely. Zachary Fairfull, a 10-year-old science buff, loved all the live demos. “It was interesting to know that people see animal properties and then put them into projects or robots.” Amy O’Neill, development coordinator for the zoo, says Wild by Design helps make a strong argument for wildlife conservation. “It shows kids that there’s another reason to pay attention and take care of all the species on the planet, beyond them just being beautiful or cute,” she says. “Having biodiversity also provides something for us.”

|

2013 Carnegie International · Artist as Activist · History Redux · Artists In Their Own Words · Frozen In Time · The Stand-In · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Lauren Talotta · Science & Nature: Cultural Craftsman · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |