|

||||||||||||

|

|

Frozen in Time

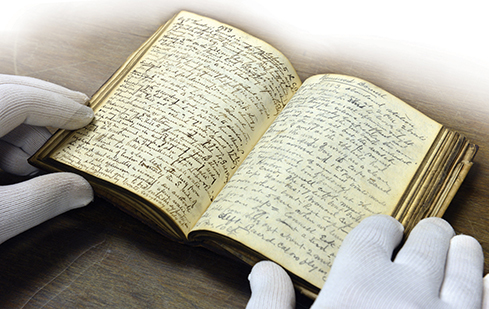

Carnegie Museum of Natural History houses the only known surviving plants from one of America’s most harrowing scientific expeditions.The small, leather-bound diary is tattered, its pages stained and yellowed from the Arctic elements and the passage of nearly 130 years. In its last entry, made by Sgt. David Ralston in perfectly slanted cursive, desperation had crept into the otherwise detached and scientific prose. It was made on January 27, 1884—four months before he starved to death.

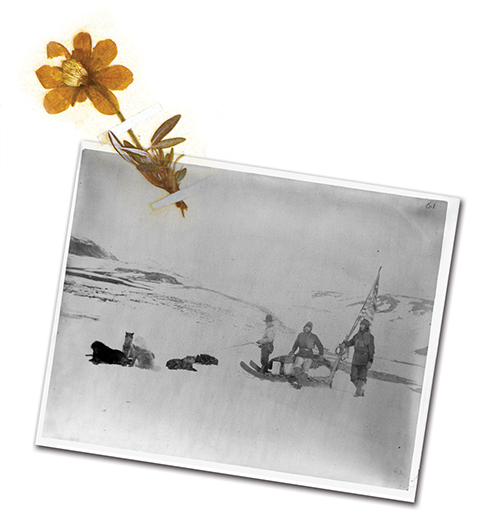

Today Ralston’s diary is housed in the archives of Carnegie Museum of Natural History at a time when interest in the Greely Expedition is resurging. The trip involved a shipwreck, a near-mutiny, and cannibalism. What’s often forgotten is that before succumbing to starvation, the participants also gathered reams of climatic data about the Arctic—much of which is now informing 21st-century research on climate change. Museum staffers, including Cynthia Morton, the associate curator of botany, rediscovered Ralston’s diary in 2003 when they were moving items out of a Carnegie Museum storage facility. Morton picked it up and thought, Now this is interesting. Her enthusiasm heightened after she and her colleagues compared the hard-to-read sentences in faded lead pencil to a typed transcript posted online. Comparing the two word-forword, Morton realized she was holding the authentic diary of Ralston, a botanist and meteorological observer who hailed from Jefferson County, Ohio, just across the Pennsylvania border. Morton became even more intrigued when she realized that the museum had more than 50 plant specimens collected and preserved by Ralston during the expedition. As far as she knows, Carnegie Museum of Natural History is the only institution to have any botanical specimens from the Greely Expedition. The Smithsonian has sleds, furs, and other artifacts, but no plants. “How did you get them?” curators from other museums asked her. Morton isn’t exactly sure. The archival record shows that the diary and plants were bequeathed by the Sgt. D.C. Ralston Estate on July 14, 1978, but there’s no mention of whether they were given by a descendant, lawyer, or other intermediary. “It’s a mystery as to why it was given to us,” Morton says. “Maybe the family was cleaning out the estate and we were the closest herbarium.” The plants are Arctic dwarf versions of poppies, buttercups, ferns, and other species. Morton was immediately impressed by how Ralston pressed the specimens and laid them out so the reproductive features were visible. “It was well done,” she says. “He was a good botanist.” Pointing to the small plants, she notes: “They have unique characteristics in dwarfism. Think of the poppies in your backyard. They are maybe a foot and a half tall. These are maybe six inches tall because of the shorter growing season.” Perhaps the greatest significance of the rare specimens is that they survived the grueling expedition at all. “These plants could have been eaten,” Morton says. “I am dedicated to science, but I’m sorry. Yum. Yum.” Near the end, the men were so overcome with hunger that they ate their shoe soles, candle wax, and seal blood, something that repulsed Ralston initially until he finally relented. Aug. 25, 1883 Fred shot a small seal - number of the men drank some of the blood - disagreed with some of them - Doctor tried to get me to drink some but I couldn’t do it. Sept. 4, 1883 4:40 P.M. Jens has just shot and secured another small seal. The vampires are turning out for a drink of blood. Sept. 24, 1883 Tea ration cut down to half teaspoonful per man - living on seal now - enough yet for 3 days - went to bed hungry tonight at 4:30 P.M. Latitude 78 degrees 49, and closer to shore than we have been yet. - David Ralston’s Diary

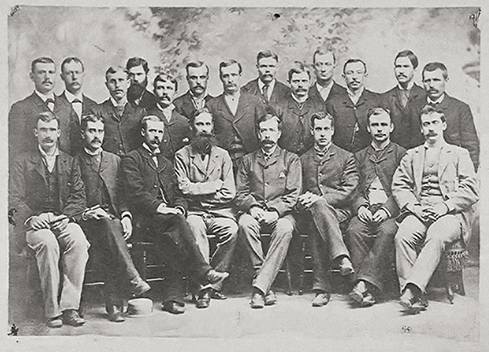

Science vs. FameOn July 7, 1881, Ralston, a 34-year-old U.S. Army sergeant, and the rest of the crew boarded the Proteus out of St. John’s, Newfoundland, and headed for Ellesmere Island, 500 miles from the North Pole. The trip was organized as part of the First International Polar Year, a push for Arctic exploration that stressed hard scientific data over glorygrabbing exploits. “The idea was to get away from the mad dash to reach the North Pole that culminated in flags being hoisted in the ground and bragging rights,” says Michael Robinson, an associate professor of history at Hillyer College at the University of Hartford and an expert on the Greely Expedition. “The idea was to collect serious scientific data because it would help scientists understand the climate of the world. There were high hopes for this expedition.” Arctic explorers were the rock stars of their generation, venerated for their bravery and the risks they took. Greely, a native of Massachusetts, was considered a natural choice for such a high-minded excursion because of his leadership role in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, a little-known unit that strung telegraph wires across the country and simultaneously collected climate information. “But just because you put down telegraph wire in New Mexico doesn’t make you a natural leader of men in the Arctic,” Robinson says.

The following month, the boat reached the arctic waterway of Lady Franklin Bay on the coast of Ellesmere Island and dropped off the team of 25 men. They built a shelter and named it Fort Conger. The scientists meticulously collected data on everything from atmospheric pressure to temperature to relative humidity to magnetic variation. Two teams could not resist the urge to compete while trying to topple the British record of furthest man north. One group eventually earned bragging rights by reaching the island’s north coast—four miles farther than the British had ventured. Then monotony set in, especially during the winter months, which brought 24-hour darkness. As spring approached, the crew waited in vain for more food. In 1882 and 1883, separate rescue ships carrying provisions failed to reach Fort Conger. The first was turned back by impassable ice. The second, the same Proteus that had brought them to the island, went down in a shipwreck. “ These plants could have been eaten. I’m dedicated to science, but I’m sorry. Yum Yum.” - Cynthia Morton, The Museum of Natural History's Botanist

As the realization sunk in that the food was not coming, Greely decided to act. Following detailed instructions left by his military superiors, he ordered his crew onto a small boat and headed south. Some of the men thought it was foolhardy to leave shelter and food for treacherous and unknown waters. Talk of mutiny circulated. “His men believed that Fort Conger was in good shape,” Robinson says. “Why should they abandon the safety of camp?” The long trip and the disaffected crew brought out the worst in the embattled Greely. “To be fair, it would test anyone,” Robinson says. “But he could be very brittle as a commander. He tended to take the men’s frustrations personally. He saw insubordination where there wasn’t any.” They landed at Cape Sabine, a desolate outpost with no shelter and hardly any provisions. At this point, says Robinson, Greely became more paternal, looking out for his crew. But hunger and hypothermia set in, demoralizing the men. Back in the United States, the rescue of the Arctic explorers was hardly a top priority. There was no sense of urgency on the part of Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln (the president’s son), who was at best a tepid supporter of the expedition. Some in the military poohpoohed the expedition because of its scientific focus. “Once the rescue failed, there was a real question whether to send another ship,” Robinson explains. But Greely’s wife, Henrietta, tirelessly lobbied both the press and politicians to fund another rescue mission. “She put up a big stink,” says Morton. “That was unusual for a woman of her time.” The third ship arrived too late for most of the crew. The first man died Jan. 18, 1884, and Ralston died on May 23. Another man died after being shot by Greely for stealing provisions. In June, a rescue team finally arrived and found seven emaciated men barely clinging to life. The rescue happened just in time. “In a matter of weeks, they would have all been dead,” Robinson says. In fact, another died on the trip back. When the six survivors of this gruesome ordeal landed in Portsmith, N.H., they received a hero’s welcome, complete with a parade. But weeks later, when the flesh-eaten corpses were exhumed from sealed graves, the tide turned. When questioned, Greely said he was not aware of cannibalism; and, if anything, the men were using the human flesh to attract shrimp. Not everyone was convinced. “You would think to look at him, he had quaffed society sillabub [traditional English dessert] all his life and had never eaten raw Marine or stewed sailor,” printed The Buffalo Express. Over a century later, the view is different. “Why would people be so judgmental?” Robinson says. “It points out how Arctic explorers were icons in American culture. It’s like athletes today who become iconic figures. They are held up as idols and then someone finds out they have cheated on their wives or gambled. The press goes crazy for three days and then they relax. These celebrities are human, after all.” An Enduring LegacyMuch like Lewis and Clark’s expedition, Greely’s only became important long after the fact. The climatic data his men so meticulously collected on Ellesmere Island is now being used by scientists as a baseline comparison in climate change research. “Whether an expedition is remembered has more to do with us than them,” Robinson says. “No one knew about Lewis and Clark until Americans became nostalgic about the loss of the West.”

Greely ultimately weathered the cannibalism accusations. He went on to become first president of The Explorers Club and received the Medal of Honor. He was also a founding member of the National Geographic Society. However, his catastrophic expedition remains his most enduring legacy. In an interesting twist in the story, Carnegie Museum of Natural History owns another relic from that voyage: Greely had mounted some Arctic plant life into a book that he inscribed: “To my daughter Rose on her 7th birthday. May her love of nature grow.” The book was donated to the museum by the late Reverend Maximilian Duman, a Benedictine monk and former president of St. Vincent College. Known as the “Arctic priest,” Duman was a botanist who made frequent expeditions to the far north. Someone gave him the Greely book, and he bequeathed it to the botany section of the museum in 1991. “It’s amazing that we got these at different times, from different people,” Morton says. Duman also donated some 15,000 specimens of Arctic plants to the museum. For Morton, it’s both fascinating and sad to look at the words and relics of Ralston, a fellow botanist who never lived to tell about his grand adventure. “He was expected to come back, but he never came back,” she says. “You know he touched this. You have something in your hands from this amazing and historical trip.”

|

|||||||||||

2013 Carnegie International · Artist as Activist · History Redux · Artists In Their Own Words · The Stand-In · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Lauren Talotta · Science & Nature: Cultural Craftsman · About Town: Wild by Design · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |