|

|||||||||||||||||

Photography by Renee Rosensteel |

Growing up a Science Rockstar

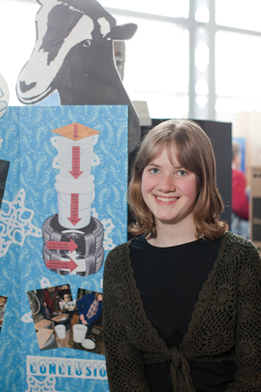

At the Pittsburgh Regional Science & Engineering Fair, science is cool, optimism runs high, and scores of young scientists want nothing less than to change their world. Two thousand years ago, Plato called necessity the "mother of invention." On March 31, 2012, in the sprawling meeting spaces of Pittsburgh's Heinz Field, 1,100 inventive minds— all under the age of 18—were tackling all kinds of necessity as participants in the 73rd annual Pittsburgh Regional Science & Engineering Fair (PRSEF). Seneca Valley ninth-grader Andrew Lingenfelter just knew he could match wits with the "teams of engineers working months and years" on prototypes of the next-big-thing in military robots, which perform everything from reconnaissance missions to sentry-guard duty. And it seems he has. "I used readily available materials, not specially purposed materials," the shy inventor explains about his success at designing a low-cost, versatile military robot. "And it was just me for most of the development." He estimates the cost of producing his open-platform "bot" to be around $5,000, versus the $200,000 price tag for similar prototypes that he read about in a Popular Mechanics article a few years back.

"Of all the robots I've seen today, this is the most impressive," remarks one bowled-over judge in a hushed tone to his peers in the senior Engineering-Robotics judging category. That afternoon, a number of sponsors would shower Lingenfelter with awards, which take the form of cash, certificates, medals, or scholarships. As the category winner, he also moved on to the International Science and Engineering Fair in May (ISEF). The mother of all science fairs, ISEF was held in Pittsburgh this year thanks to the caché of Carnegie Science Center, the organizer of the annual Pittsburgh science fair, which is one of the oldest in the country. "You hear all the bad things going on in the world, but you come here and think, 'okay, there's hope!'"

- Amy pare, science fair judgeNorwin High School senior Rachel Lojas has a less lofty but no less important end goal for her project: She wants to help her aunt, who has bad knees, know exactly when to water her garden plants—specifically, her pea plants. "I wanted to figure out a way that her plants could tell her when they needed water, so she didn't have to worry about watering her plants every day," says Lojas, who plans to become a nuclear engineer. Her inspiration comes from water sensors that she and her classmates constructed in their electronics class using copper-wiring boards. "A buzzer went off when rain hit the copper boards, and I thought, 'wow, this is really cool to have something so simple that could be so useful.' So I created something similar to insert into the dirt, but instead of a buzzer I put in a light." Lights out and it's time to water.

Then there's high school senior Natalie Nash, of Vincentian Academy, who for the second consecutive year took home top prize in the Computer Science-Math category. "People with disabilities are really my main focus," she says in her rapid-fire yet measured and precise science-fair speak. "I want to help improve their lives with the technology we're developing every day." A comp sci Pollyanna? Think again. This petite, high-heeled inventor is dead serious.

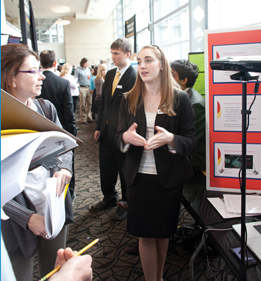

Scientist, Teach ThyselfBy noon the day of the science fair, Nash's voice is cracking. She'd been giving her pitch to countless passersby all morning—noticeably more than her neighboring exhibitors, a sure sign that what she'd created was something special. It isn't easy getting noticed in this crowd, with 300 students in the senior division, twice that many in the seventh- and eighth-grade division, and the sixth-graders numbering more than 200.

"People with disabilities are really my main focus. I want to help improve their lives with the technology we're developing every day."

- Natalie NashTo anyone interested in engaging her, Nash displays just the right combination of eagerness and constraint. But when given the green light, she takes off like a race horse released from its starting gate. "I've always been interested in computers and integrating technology to help address the physical problems that people have," she says. "The problem that I wanted to help solve this year was the problem that visually impaired people have when navigating in an unfamiliar environment. So I used the Xbox Kinect, which is a gaming system, and my laptop and an iPhone, and I developed an application that could tell people where objects are located."

The visually impaired user simply places a finger across the screen of the iPhone, and when approaching an object the iPhone screen both turns a bright red color and vibrates. Nash says she wrote the app's program in C and objective C—programming languages she'd never used before. She taught herself in her spare time. This is Nash's sixth and final year at the Science Fair. Last year she worked on a "digital keyboard" that increased the speed at which individuals who can't speak can communicate through a computer that gives voice to typed words. Ever the ambitious inventor, Nash says she'd next like to adapt her current invention so it can detect stairs. "With the coordinate system that I developed, I'm working on algorithms now, and I'm also hoping to incorporate audio cues."

Hope for tomorrow"The Science Center is known throughout the region as a great place for interactive, hands-on experiences that teach about science in ways that are fun," says Ron Baillie, co-director of the Science Center. "But we also have a serious mission to excite and inspire young people to explore careers in science, technology, engineering, and math—also known as STEM." That mission took flight in a big way last November when the Science Center launched its Chevron Center for STEM Education and Career Development, which counts the regional science fair as one of its programs. The Science Center and its numerous corporate and educational partners now have their laser-like focus on one goal: inspiring the workforce of tomorrow to get interested in science and technology today. "Getting kids fired up and equipping them with the skills they need requires a collaborative effort involving many different stakeholders," adds Ann Metzger, Science Center co-director. "Teachers, industry, parents, students." And judges.

"They always come through; and they really enjoy doing it," says Kosick. "We had a record number of category judges this year—375." "It's a fun process," says a smiling Andrej Savol, part of the joint Carnegie Mellon- University of Pittsburgh PhD program in computational biology and a second-year category judge. But judges feel the pressure, too. "You kind of end up rooting for the person you think is best, but then maybe someone else is able to advocate for a student who is just, frankly, incredibly impressive. And it can get nerve-wracking, because you don't want to look like a doofus in front of your peers!" he adds, laughing. David Koes, a Ph.D. in computer science and a research assistant professor in computational and system biology Pitt, served on the judging team that selected Natalie Nash as the winner in the Computer Science-Math category. While he enjoyed his first experience as a judge, he couldn't help lamenting the lack of computer science instruction in high schools. "Most of the students say they don't have a formal computer science course, which is a little depressing to me," a forlorn Koes notes. "But I guess when you look at it from that perspective and you see what they manage to accomplish anyway, it's very impressive." Maryann Miknevich, a rehabilitation physician, is a 10-year veteran of the judging core—as both a category judge and a corporate-sponsor judge for the Allegheny County Medical Society, one of the event's more than 100 sponsors, for which she serves as president. All told, this year's sponsors gave $1 million in prizes and scholarships. "There's so much enthusiasm among the students," she says, "and I think we've also seen an increase in the sophistication of the projects. Some of them are just incredible. There are senior high school students that seem to know more than I do!" Her colleague, Amy Pare, a surgeon at St. Clair Hospital, is newer to the process and not afraid to gush. "You hear all the bad things going on in the world, but you come here and think, 'okay, there's hope!'" During the afternoon corporate-sponsor judging session, Miknevich and Pare have the pleasant task of giving out awards on behalf of the Allegheny County Medical Society. But it's hard to figure out who's more pleased—the judges or the student winners. The New Cool KidsThe gravity of STEM programs like the regional science fair couldn't be any greater than it is at this moment. Eight out of the 10 fastest-growing occupations are related to math, science, or technology. Regionally, more than 200,000 new STEM-related professionals will be needed within the next 10 years. Yet the United States is woefully behind the eight ball when it comes to teaching and inspiring its future scientists and engineers.

In 2011, Will.i.am of The Black Eyed Peas fame went all out for science when he created a back-to-school special featuring the likes of Snoop Dog and Justin Bieber giving musical high-fives to kids at a national robot competition. He also created the i.am.scholarship that supports, among other things, high school academic mentoring. "Technology is recession proof, and most kids are not dreaming of being programmers, scientists, or engineers. The ones that are do not get the spotlight or attention," he said at the "science-is-rock-and-roll" event. "Instead, they are looked at as geeks or uncool, when in actuality technology is the only thing that is cool today." Cool or not, science rock star Natalie Nash just knows that science is her future. "Science fairs have just completely changed my life," she says emphatically. She now wants to return the favor.

|

||||||||||||||||

First Impressions · GUITAR · Manufacturing Ideas · Special Section: A Tribute to Our Donors · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Russ Christoforetti · Artistic License: The Power of the Painter · Field Trip: Appalachian Wonder · Science & Nature: Taste the Rainbow · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |