|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Grands Boulevards, 1875, Philadelphia Museum of Art: The Henry P. McIlhenny Collection in memory of Frances P. McIlhenny, 1986 |

First Impressions

Critics called them crazy, and worse. But the fearless Impressionists held their ground and changed the way we see.

On April 15, 1874, an art exhibition opened on the fashionable Boulevard des Capucines in Paris, and the public gasped. This was art? Many of the gallery-goers scorned it as foolish, incompetent, and incomprehensible. A critic would later liken the modern paintings to something hatched inside an insane asylum, and a cartoonist cautioned pregnant women not to view the shocking paintings. The painters knew they would create a scandal. After all, they had risked their careers by bucking the establishment of the Paris Salon, with its jury system that celebrated traditional paintings with detail-filled polished surfaces. These radical artists who painted subjects of modern life with broad, gestural brushstrokes and an unusually bold color palette called themselves the Anonymous Society of Artists, Painters, Sculptors, Printmakers, etc. But a critic mockingly coined them the "Impressionists" —lifting the name from a painting by Claude Monet. Today the artwork of Impressionist masters is so beloved that reproductions adorn the walls of countless residence halls and waiting rooms. But when they introduced their work in eight revolutionary shows from 1874 to 1886, the Impressionists were outsider bohemians. That whiff of scandal in 19th-century Paris now permeates Carnegie Museum of Art's Heinz Galleries where Impressionism in a New Light: From Monet to Stieglitz is on view through August 26. "It was worth seeing for the same reason that one would go to see an exhibition of pictures painted by the inmates of a lunatic asylum."

-The American Register, 1879, about The Exhibition of the ImpressionistsThe exhibition showcases 150 works, mostly from the museum's permanent collection, including masterpieces by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Cézanne. This exploration of Impressionism differs from others in that the famous paintings, pastels, sketches, and prints are displayed alongside Pictorialist photography by Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, Gertrude Käsebier, Clarence H. White, and others. Pictorialism embraced a purposefully soft-focus style that, influenced by Impressionism, developed more than a decade later and helped establish photography as fine art. Impressionism in a New Light investigates what the movement means both as a historical phenomenon and an approach to art-making. Painting may be the first form of art that comes to mind when thinking about Impressionism, but the same artistic concerns can also be found in prints, drawings, pastels, photographs, and sculpture. The museum devotes one gallery to discovering the visual dialogue between photographers and artists working in other media.

"You may not yet care for this kind of painting, but… you will."

- Édouard Manet, March 19, 1877

"Impressionist painters were experimenting with cropping in response to compositions they observed in photography," explains Amanda Zehnder, Carnegie Museum of Art's associate curator of fine arts and the exhibition's co-curator. Linda Benedict-Jones, the museum's curator of photography and fellow co-curator, adds, "Pictorialism was called 'fuzzy graphics.' Impressionism was called 'fuzzy art.'" Lynn Zelevansky, The Henry J. Heinz II Director of Carnegie Museum of Art, has wanted to host a major Impressionism exhibition since her arrival at the museum in 2009. Walking the galleries early in her tenure, she saw a teenage girl peering up at the museum's prized Monet Water Lilies panel. "Oh, this can't be real," she overheard the young girl tell her friend. "It's Pittsburgh." Then and there Zelevansky vowed: I've got to do something about that. Pittsburgh needs to know that their museum has an Impressionism and Post-Impressionism collection to be proud of. While in recent years visitors have viewed the well-known paintings scattered throughout the Scaife Galleries in chronological order, alongside many different contemporaneous styles of art, Impressionism in a New Light gathers key works into a concentrated burst and showcases great Impressionists from around the world. And as visitors swoon over the masterpieces of Monet, Camille Pissarro, Édouard Manet, and Paul Gauguin, they encounter period quotations that capture the outrage of their 19th-century critics. Zehnder and Benedict-Jones culled through old journals, essays, and critical reviews to find the vitriol. Politician and art critic Jules-Antoine Castagnary exclaimed, "Ces terribles révolutionnaires" in 1874. "The Exhibition of the Independents is closed for this year," said The American Register on May 18, 1879. "It was worth seeing for the same reason that one would go to see an exhibition of pictures painted by the inmates of a lunatic asylum." The curatorial duo compiled 43 pages of lively quotes. The hard part was narrowing down the list. As Benedict-Jones says of the critical reaction to both Impressionism and Pictorialism, "It was an embarrassment of riches."

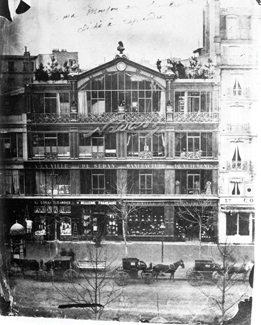

Most people think I paint fast. I paint very slowly. Before he became the most famous artist in art-obsessed France, Claude Monet was a bohemian, barely scraping by. He rebelled against his parents, the art establishment, and any rule that ever tried to make him conform. "I was born with a lack of discipline," he once said. "No one was ever able to make me stick to the rules, not even in my youngest days." Monet grew up on the coast of Normandy, drawing caricatures initially. As a teen he met Eugène Boudin, an older artist who encouraged him to paint outdoor landscapes. Monet's contrarian nature made him a natural to help define the new techniques of Impressionism, defying the classical rules of composition to capture shapes and colors as he actually saw them. An Impressionist who ventured into the field might paint a cloud or a snow bank in purple instead of the predictable white of popular imagination. The color schemes, the gestural brushstrokes, and the asymmetrical cropping challenged the popular notion of what constituted a beautiful painting. In 1868, Monet painted the abstract landscape The Sea at Le Havre with such energetic brushstrokes that the crashing waves look almost sculptural. Monet and rebels like Cézanne, Renoir, Degas, Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley had broken with time-honored conventions for producing art. They wanted to hold their own exhibition far from the Salon. But where? They approached the famed photographer Nadar, who had a large gallery with big glass windows, a perfect light-drenched space in an era before electricity. Nadar agreed to host the scandalous show in his airy quarters. With his red cape and one-name status, Nadar, who climbed aboard a hot-air balloon to make images of Paris, was at that time a much bigger star than the painters. The show opened in his fashionable and spacious studio, which is pictured with its modern façade in one of the exhibition galleries.

The early reviews of the original Impressionist show were brutal. But an undaunted Édouard Manet mused in a letter dated March 19, 1877, "You may not yet care for this kind of painting, but … you will." That statement proved prophetic. Monet and the other Impressionists became famous in their lifetimes. At the time of his death in 1926, Monet was a state-sponsored artist commissioned to paint his Water Lilies panels for the Orangerie in Paris' Tuileries Gardens. The former rebel hobnobbed with dignitaries, including the prime minister. Photography Gains Art-world CredWhile Impressionism was sending shock waves through the Parisian art world, across the ocean a group of New York photographers was also pushing back against the establishment. They were alarmed by the 1888 invention of the Kodak camera by George Eastman, which was suddenly opening up photography to the masses. Alfred Stieglitz, a brilliant editor and photographer in the Camera Club of New York, bemoaned "the deluge of ordinary photographs."

In the early 1900s, Stieglitz put out the first issue of the acclaimed journal Camera Work, originally for $2.50 a year. "Camera Work journals were beautiful," says Benedict-Jones. "A single volume would include eight to 10 photogravures, the most beautiful method for mechanical production of photographs to this day." In 1902, Stieglitz broke with the Camera Club of New York, believing it had become too stodgy. He wasn't someone who believed in compromise. "He was a tyrant," Benedict-Jones says.

But through trial and error, the early Pictorialists created masterpieces, sometimes by manipulation with brushwork in the printing process, or occasionally by spitting on or loosening their camera lenses to get the desired effects. Stieglitz's photograph The Terminal, on loan for the exhibition from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, shows a horse-drawn omnibus paused on the slushy streets in front of the old New York Post Office. "Its gauzy focus romanticizes the daily struggles of city life by making it somewhat dreamlike rather than sharp and crisp," says Benedict-Jones. The Pictorialists realized their goal of elevating their craft in 1904 when the galleries at Carnegie Institute (precursors to the Museum of Art) held a show of their work, organized by Stieglitz and Steichen. "It was a significant feather in our cap," says Benedict-Jones. "Pittsburgh was an early leader in recognizing photography as an art form." "Pictorialism was called 'fuzzy graphics.'

Impressionism was called 'fuzzy art.'" - Linda Benedict-Jones, curator of photography

But Stieglitz's imperious nature led to clashes with other photographers, notably Käsebier. Independently wealthy, Stieglitz could afford to be uncompromising in his artistry. But Käsebier, unhappily married and separated from her businessman husband, was forced to earn a living from her craft. She started selling evocative images of celebrities, and intersected with one of the biggest murder scandals of the century, which just so happened to have rich Pittsburgh connections. A Hint of ScandalIn 1903, Stanford White, the famous New York architect, walked into Käsebier's studio and asked her to photograph his beautiful teenage girlfriend, Evelyn Nesbit, a model and showgirl who grew up in Tarentum, Pa. The breathtaking Nesbit would go on to marry Pittsburgh industrialist Harry Kendall Thaw, who was jealous of her past relationship with White. On July 26, 1906, inside the rooftop theater at Madison Square Garden, Thaw shot White three times, killing him. At the first trial, Nesbit testified in her husband's defense, and the jury was unable to reach a verdict. In the second trial, Thaw was found not guilty by reason of insanity, and spent the rest of his life in and out of insane asylums and the courts.

The same focus on young girls was also evident in Impressionist paintings, notably in Degas' images of ballerinas. "Degas often depicted men backstage and mothers who were there as chaperones, but who also sometimes facilitated connections." Zehnder says "Ballet dancers were working-class girls—not high-class—nicknamed 'the rats.''' Zehnder notes there are other parallels between the two art forms. The pastel Dancers, Entrance on Stage has an asymmetrical cropping, something Degas and others learned from the language of photography. Then there's Renoir's The Grands Boulevards, on loan from the Philadelphia Museum of Art. It shows a wide, magnificent boulevard with a white horse coming into focus while the rest of the painting is hazy, as if in peripheral vision. "That was the kind of thing that critics had a hard time understanding in the 19th century," says Zehnder. "It looked unfinished, disorganized, and blurry to them." Benedict-Jones added that this, too, was something learned from photographic lenses. It was called depth of field, and it was a way of seeing that had gone unnoticed prior to the introduction of the camera lens. "They went from being radical to being accepted. They transformed what we think of as a beautiful painting.''

- Amanda Zehnder, associate curator of fine artsEven childcare was depicted in a new way. The exhibition includes the museum's newly acquired pastel by Mary Cassatt, Mathilde Holding Baby, Reaching out to Right. While the figures' hands are intertwined, the woman's expression is unreadable and the baby is reaching out to something beyond the frame, teasing the viewer. Cassatt was a Pittsburgh native (Allegheny City) who moved to Philadelphia with her family as a child and then settled in France permanently in 1874, the year of the first Impressionist exhibition. She was one of only three women and the only American to show with the French Impressionists. Early in her career, she had much success with the Paris Salon and had to ponder whether she wanted to gamble and join the ranks of the scandalous Impressionists. Cassatt was invited to join the group by Degas in the mid-1870s. She thought about it for two years before debuting her Impressionist work in 1879. "There was every likelihood that this decision could have ruined her career," notes Zehnder. Zehnder likens the great risks the Impressionists took to the way Beatlemania challenged our established notions of popular music. "The Beatles started out being very shocking and making people scream over haircuts," she says. "Then everybody loved The Beatles. That is a good metaphor for what happened with Impressionism. They went from being radical to being accepted. They transformed what we think of as a beautiful painting."

|

|||||||||||||||||||

GUITAR · Manufacturing Ideas · Growing Up a Science Rock Star · Special Section: A Tribute to Our Donors · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Russ Christoforetti · Artistic License: The Power of the Painter · Field Trip: Appalachian Wonder · Science & Nature: Taste the Rainbow · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |