Summer 2012

Summer 2012|

"He's a master of material. His deep exploration of the subject of painting takes him into new territory— into what paint can do."

- Warhol Director Eric Shiner |

The Power of the Painter

New York artist Donald Moffett has made a career out of pushing boundaries. Donald Moffett's meticulous deconstructions of the traditional canvas, with zippers, ornate ribbons of paint, holes, and video projections, suggest that the medium is his only message. But the artist sees his latest exhibition of work as the evolution of a career that has been propelled by political and public issues since he arrived in New York City in 1978.

"In its opened-up form, it's all about liberation," the 57-year-old painter says of the first comprehensive survey of his work, opening June 23 at The Andy Warhol Museum. Donald Moffett: The Extravagant Vein, organized by the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, speaks to the artist's continued investigation of art history, paint, and form over 20 years, highlighting his thoughtful engagement with politics and technology. The retrospective has enhanced Moffett's international reputation, says Warhol Director Eric Shiner. "He used to be under the radar of mainstream, but that has radically changed in the past few years," says Shiner. "This exhibition has drawn attention to his incredibly strong work." Critics agree. "Moffett manages to make political art that is subtle and art about art that is also about much more," wrote reviewer Amy Griffin during the exhibition's most recent appearance at The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, New York. Subtlety was decidedly not the point of the works that brought Moffett early recognition. Within a few years of arriving in New York from San Antonio, he was galvanized by the AIDS crisis to create guerilla poster art challenging governmental inaction. Adorned with the face of then-president Ronald Reagan and emblazoned with the slogan, "He kills me," that famous 1987 activist art will be reproduced as wallpaper at the entrance of the exhibition.

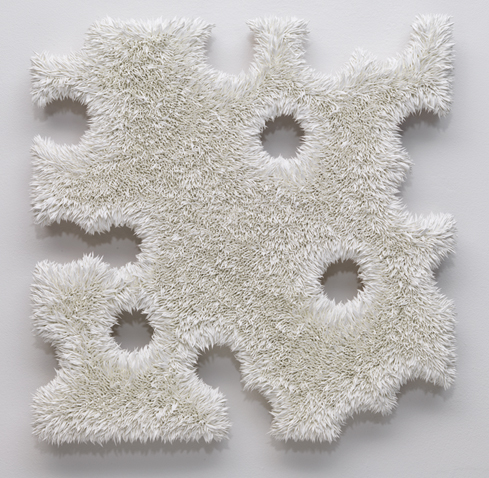

Moffett went on to challenge perceptions of gays in several series of works on paper. In Gays in the Military (1990) and Nom de Guerre (1991), he combined historical portraits of military celebrities with humorous, subversive texts. By the mid-1990s, Moffett's mood and means shifted. In 1996, he showed a group of small abstract paintings that signaled new interests. By 2000, he began experimenting with "light loops," in which he projected video images on painted canvases. He explored the combination of metallic canvas surfaces and video projections of The Ramble, a lush Central Park site for both gay cruising and gay bashing. The series, created in 2003 and titled The Extravagant Vein, layers landscape painting with political overtones. In his 2005 work Hippie Shit, Moffett added a 1970s harmonica soundtrack to a group of monochromatic paintings; a year later, in Impeach, he let sound stand alone. The two-minute installation includes audio of a speech by John Lewis, a democratic legislator and Civil Rights leader from Georgia, arguing metaphorically against the impeachment of President Bill Clinton. Moffett admits that over time, "The voice has changed, the work has changed. Across the years, the work has opened out in a less verbal and less didactic way. There is an arc to a lifetime and to emotional capacities, [but] the issues, the content, the politics is a thread running throughout. Politics change, and any articulation of them through art changes too." Moffett's alterations of the painting canvas include adding zippers to the geometric compositions of Gutted and suggestive round holes to the surfaces of Fleisch, both created in 2007. For a series dubbed Comfort Hole, the artist drew from his training in cake decorating to create shaggy, looped, and textured surfaces from extruded paint.

Shiner particularly praises Moffett's Comfort Hole paintings, in which paint is made to stand up, rather than lay flat. "He's a master of material. His deep exploration of the subject of painting takes him into new territory—into what paint can do." It's this work that makes his move to new territory explicit, says Moffett. "That work is the beginning of the exhibition that I just wrapped up in New York—the painting has been moved off the wall, onto a homemade contraption, a post in a bucket of cement. It's a metaphor, but it's honestly moving away from the wall—because the wall has presented limitations." Despite those limitations, the artist believes that painting "is extremely vital right now. As a function of that, my work is about expansion—expanding commonly perceived limits of painting. This is great fun—to dream about pushing [the boundaries] elsewhere. Art and art forms at the moment are so big, painting is only a subset. But that doesn't diminish the explosive dynamism of what I see. Painting is being deformed and deconstructed in great ways," he says, citing the work of young artists Dianna Molzan and Charlie Hammond.

|

First Impressions · GUITAR · Manufacturing Ideas · Growing Up a Science Rock Star · Special Section: A Tribute to Our Donors · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Russ Christoforetti · Field Trip: Appalachian Wonder · Science & Nature: Taste the Rainbow · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |