|

||||||||

|

Sculptor Dee Briggs, who lives and works in New York and Pittsburgh, checks out an ultra high-performance concrete panel at TAKTL's Glenshaw plant, with TAKTL's Garret Smith.

Photography by Renee Rosensteel

|

Manufacturing Ideas

The Warhol brings together art and industry as a way to reimagine Pittsburgh. Amid the cubicle culture of One Gateway Center in Downtown Pittsburgh, ORLAN stands out. On appearances alone, the internationally renowned French artist might seem miles removed from even the new-economy offices of BodyMedia, the Steel City-based company that produces the fitness-tracking armbands that have captured her attention. But while the looks of this 65-year-old performance artist with half-and-half shock-white and pitch-black hair and fluorescent-yellow spectacles don't exactly scream "corporate," the discussion between ORLAN and BodyMedia's Director of Hardware Development Scott Boehmke is all business. Boehmke shows ORLAN the BodyMedia FIT Armband in minute detail. Through a translator, the artist meticulously inquires about how the device monitors everything from a user's heart rate and sweat production, to quality of sleep. As she notes the names of its metals, ORLAN's husband, art historian and writer Raphael Cuir, photographs the product in detail. "I love to see the insides," says ORLAN in English, slyly pursing her lips. "I am that kind of woman." ORLAN is in town as part of The Andy Warhol Museum's upcoming Factory Direct: Pittsburgh, an exhibition of newly commissioned work created by 14 internationally known artists in collaboration with Pittsburgh-area "factories": companies that, in one form or another, create and manufacture a product. Between March and June of this year, each of these contemporary artists—including three already based in Pittsburgh—took up residencies of various length in the city and collaborated with their factory partners to develop new work. For ORLAN, BodyMedia is a perfect fit: The artist's penchant for creating visual and performance works based on her own body, including her famous series of plastic surgeries in the 1990s, made BodyMedia's cutting-edge bio-data technology an obvious choice. Other artist- factory pairings perhaps aren't so cut- and-dry. Japanese artist Tomoko Sawada, known for her playful self-portraits, for example, worked with Heinz. The artists are internationally-minded, the companies diverse in size, scope, and product, and even the show's site contributes to its theme. Rather than inside The Warhol's galleries, Factory Direct, opening June 23, will take shape at Guardian Self-Storage on Liberty Avenue in the Strip District. "We wanted to bind the old with the new," says Eric Shiner, director of The Warhol and curator of Factory Direct. "And what better way to infuse the past, present, and future than with contemporary art—with artists who can look at this city's legacy and take it to a new place?" Assembly Line DeconstructionIn the tradition of Andy Warhol's Factory—the artist's studio where he created the assembly-line-like, art-production ideas that catalyzed Pop Art and famously fused contemporary art and commerce—Factory Direct isn't exactly a new idea. In fact, this isn't even the first time Shiner has worked on a Factory Direct exhibition. "It makes sense to do this show in Pittsburgh. Not only do we have that industrial history, but we have Warhol and his Factory—it all melds together well."

- Eric Shiner, director of The WarholAs a graduate student at Yale, Shiner worked with curator Denise Markonish at Connecticut arts organization Artspace on Factory Direct: New Haven, a show with similar parameters comprised of regional and New York City artists and New Haven factories. (One of that show's participants, artist Michael Oatman, created the first Factory Direct show in Troy, New York, in 2001.) The 2005 New Haven show was successful in several ways—from garnering positive press in The New York Times, to a partner company adopting its resident artist's ideas for a new product line, to participation from local government and business figures. It also dissolved often firm lines between art, politics, and commerce. So when Shiner, a University of Pittsburgh graduate, returned as The Warhol's Milton Fine Curator of Art in 2008, one of his first thoughts was Factory Direct. "As the hub of innovation and industry at the turn of the last century, it makes sense to do this show in Pittsburgh," says Shiner. "And not only do we have that industrial history, but we have Warhol and his Factory—it all melds together well." His subsequent shift in responsibilities isn't the only thing that's led to a long gestation period for Factory Direct: Pittsburgh. It's a complex exhibition to mount. Besides choosing the 14 artists, Shiner and his staff developed a list of 75 partner companies for them to choose from. These include local heavyweights such as Heinz and Alcoa, as well as new, smaller companies such as BodyMedia, architectural product designers Forms + Surfaces and TAKTL, and Construction Junction, Pittsburgh's only non-profit building material reuse retailer. Each artist named their first, second, and third choice, and, fortunately, all 14 made different first-round drafts.

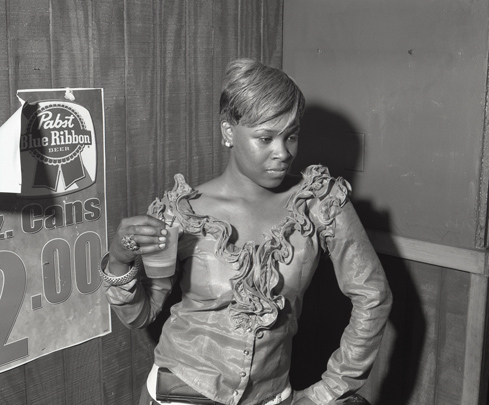

Tomoko Sawada wasn't interested in the well-known corporations—at least not at first. The 35-year-old artist splits her time between New York City and her native Kobe, Japan, and had The Warhol's list of factories in mind as she traveled between her two bases. "Heinz is a very strong [corporate image]," says Sawada, "and I was thinking it's not good for me to work with such a strong company, so I was picking another one. But something didn't feel right. And I was in New York, walking past a café with outside seating, and on each table was a Heinz bottle. That's when I looked at it and realized the ketchup had a face." Faces, and the contexts we project upon them, are integral to Sawada's work. Her breakthrough artwork ID400 comprised 400 photo-booth self-portraits, each in a completely different guise. For her work with Heinz, the artist centered in on the iconic ketchup bottle to make 56 photographs, each an iteration of the label translated into a different language. "Heinz is such a famous company. Everybody knows its logo," says Sawada. "I want to change the logo, like changing my makeup." British photographer Mark Neville's work in Pittsburgh is about a rather different product locally "made." Conceptually, Neville is exploring the legacy of steel production, creating social documentary photographs of the industry's most enduring product: Pittsburgh. "It's a poetic partnership," says Neville. "I'm looking at the legacy of the steel industry from a social documentary perspective— a legacy that's revealed through the photo-graphs, even if it's in the subtext rather than being explicit." The project relates to other work Neville has done, including a book and installation of photographs from the post-industrial town of Port Glasgow, Scotland, once an internationally known shipbuilding center. The concept harkens to Pittsburgh's famed social-documentary projects of the early- and mid-20th century, which made photographers W. Eugene Smith and Lewis Hine famous. Perhaps most interestingly, though, Neville cites Gary Winogrand's 1970s images of art openings, parties, and other social events as inspiration. Neville's Factory Direct series titled Braddock/Sewickley Heights involved the artist spending six weeks in each of the eponymous neighborhoods, which most Pittsburghers would immediately recognize as being opposite ends of the steel industry's legacy. Sewickley Heights is one of America's wealthiest neighborhoods; Braddock a poor remnant of the mill closures of the early-1980s. Neville's images aren't the towering architecture of the mills, but rather the after effects of their capital and their closure.

"I'm shooting a father-daughter dance at the Edgeworth Club in Sewickley," says Neville. "It used to be that three of the top-five wealthiest people in America lived in Sewickley, and that wealth is still manifest. I think this dance is bound up with those values, and those ideas of etiquette—that kind of old-world coming-of-age rite of passage. "But I'm not going to preconceive or prejudge anything," says Neville. "In Braddock, the prejudice might be that it'll be a complete flip of Sewickley in every aspect. But I don't know what to expect; I'm keeping a very open mind, so I can let the photos speak for themselves."

Grand VisionsOther projects created especially for Factory Direct include Mexico City-native Edgar Orlaineta's work with Alcoa to reinterpret Charles Eames' Solar Do-Nothing machine, a non-specific, purposeless plaything created in 1958 as a commission for the aluminum manufacturing giant. Pittsburgh-by-way-of Florence, Italy, artist Fabrizio Gerbino is examining the work of Calgon Carbon Corporation. And New York sculptor Chakaia Booker is drawing her inspiration from Carnegie Mellon University's Robotics Institute. The collaborations aren't one-way streets. Partner companies are contributing their expertise, products, and, in some cases, their space. In return, as Shiner points out, "Artists always come at these projects with a different way of thinking, and sometimes those ways of thinking make sense for the company, as well." BodyMedia, for one, didn't need convincing of the benefit of having artists involved in their work. Ivo Stivoric, the company's chief technology officer, aims to go well beyond acting as a passive partner for ORLAN. "I know a lot of her work from being in the art and design field for years," says Stivoric. "It's interesting how she makes her life, her body, part of her research and art. And to her, the Armband became like a camera for picking up what's emanating from the body and exposing that [data] in a way that's not, 'Oh, it's a calorie counter on the arm,' but something that has a grander vision. It's about creating conversations around how people use technology and live their lifestyles. And after she completes the piece, we'll think about those things and do some post-analysis." ORLAN and the other artists will showcase their Factory Direct work at the towering Guardian Self-Storage building in Pittsburgh's Strip District, an old mattress factory. "As soon as I walked in, I thought, 'This is it,'" says Shiner. "We're showing the industry of artists, making work about the industry of a place, and it's shown in an industrial setting. It's all about the works—very Warholian." And very ORLAN. For her Factory Direct contribution, the artist wears a BodyMedia armband while measuring the ground floor of The Andy Warhol Museum. The work is an update of sorts to a series of "MesuRages" she performed for decades beginning in the 1960s, where she used her own body as a form of measurement. Using BodyMedia technology, she now measures not only in "ORLAN-body," but in temperature, heart rate, and sweat. Measuring the space of industry on a literally human scale and documenting the relics of Pittsburgh's industrial-labor past with the product of its post-industrial labor present, ORLAN's project helps make sense of the transformation of "work" from that of the group to that of the individual. It also acts as a measurement of the actual labor of art making, something that Shiner believes is at the heart of Factory Direct, and the new Pittsburgh. "The intersection of contemporary art and commerce is where Warhol comes in again, as a role model for all of the artists creating here," says Shiner, "because he was not only a master of art making, but also of the business side of his work. "We've got a lot of momentum in the art world in Pittsburgh at the moment; a lot of artists are moving here and we need to provide them with support structures. I think it'd be really interesting if companies, after seeing this show, start to think how they can engage artists more regularly."

|

|||||||

First Impressions · GUITAR · Growing Up a Science Rock Star · Special Section: A Tribute to Our Donors · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Russ Christoforetti · Artistic License: The Power of the Painter · Field Trip: Appalachian Wonder · Science & Nature: Taste the Rainbow · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |