|

||||

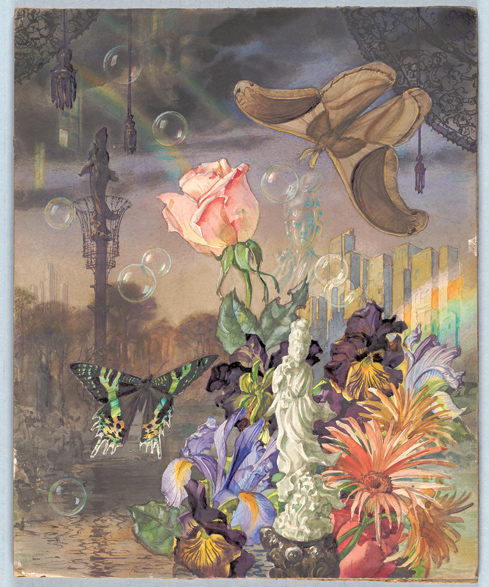

Andrey Avinoff, Detail of White Orchid, 1948–1949,

|

Chasing Beauty

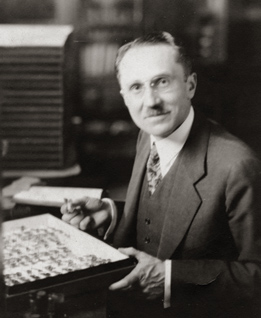

From an idyllic childhood in imperial Russia to his final days in New York City, former Museum of Natural History director Andrey Avinoff explored the worlds of science and art with equal vigor, all in the pursuit of beauty. A new exhibition at Carnegie Museum of Art is the first to reveal the true depth and breadth of his artistic vision. Legend has it that Andrey Avinoff (pronounced a-VEE-nov), born in 1884 to wealth and privilege, captured his first butterfly as a 5-year-old, at the request of a relative who wished to paint a certain species. The next day, the family artist sent the youngster off to fetch another of the winged beauties. Upon trapping his delicate prey, he noticed subtle differences between the two. His curiosity piqued, Avinoff took the first step in a lifelong journey of seeking knowledge and appreciating the exquisite elegance, diversity, and beauty of nature that would one day lead him to Carnegie Museum of Natural History, where he served as director for nearly two decades. Though Avinoff’s passion for butterflies and his expansive knowledge of them are well documented, his prolific work as an accomplished artist remained virtually ignored until 2007, when his four heirs approached Louise Lippincott, curator of fine arts at Carnegie Museum of Art. It was their wish that the museum help document and preserve their great uncle’s artwork.

As she recounted in an article published in the Spring 2009 issue of this magazine, Lippincott was pleasantly surprised to discover Avinoff’s expertise as a draftsman, commercial illustrator, and watercolorist. While she would find only a single Avinoff watercolor in the Museum of Art’s collections, she soon discovered that the Museum of Natural History owned not only Avinoff’s collection of 120,000-plus exotic and rare butterflies but also more than 400 of his botanical watercolors. “We had no idea,” she wrote. Over the past three years, Lippincott has collaborated with Avinoff’s family and her colleagues at Carnegie Museum of Natural History to track and document the art and scientific accomplishments that represent Avinoff’s wide-ranging interests in science and nature, religion, evolution, and human sexuality. The fascinating results of that research are now on display through July 24 in Andrey Avinoff: In Pursuit of Beauty, an exhibition at Carnegie Museum of Art curated by Lippincott. The museum has also published a beautiful catalogue of Avinoff’s artwork. “The remarkable thing about studying Avinoff was every time I discovered a new topic of interest to him, I knew even less about it than the previous one,” Lippincott notes. “He had a truly original mind that didn’t follow the same patterns of most people.” From Russia with butterfliesIt’s a long way culturally and geographically from Avinoff’s nearly palatial childhood home in what is now Ukraine to the hardscrabble coal and steel towns of southwestern Pennsylvania. Yet, in some ways, his arrival in Pittsburgh seemed impossibly inevitable, as it was for so many Russian and Slavic immigrants who settled in the area to work in mines and mills. “If people can see the world just a little bit the way he did, it would be a great experience.”- Louise Lippincott, curator of fine artsThe grandson of a high-ranking military man who served in the British Navy with Admiral Horatio Nelson at Trafalgar, Avinoff spent his youth in Ukraine on an expansive estate granted to his mother’s side of the family by Catherine the Great. During those tranquil times, he studied painting with his English governess, creating his first watercolors at an early age. As a 7-year-old, already armed with his first butterfly net, he cast his eyes upon The Butterfly Book by William J. Holland, the first director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History and the man who would recruit Avinoff for a position at the museum more than three decades later.

Andrey Avinoff, Frustration detail, 1948, Carnegie Museum of Art, Second Century Acquisition FundStill pursuing both of his passions as he approached adulthood, Avinoff eventually earned a law degree at the University of Moscow, which led to an appointment as a “gentleman in waiting” to Nicholas II, the ill-fated last czar of Russia. Busy with his diplomatic responsibilities, especially with the onset of the Great War in 1914, Avinoff still managed in his free time to indulge his appetite for collecting butterflies on trips to China, Tibet, and Turkistan. It was during this time that Avinoff gathered specimens that would lead to a groundbreaking discovery about evolutionary development within the butterfly genus Karanasa. “Karanasa butterflies are found in the part of the world dear to Avinoff, from the Caucasus to Hindu Kush,” says John Rawlins, associate curator of invertebrate zoology at the Museum of Natural History and a collaborator with Lippincott on her Avinoff research. “What he observed while working with his colleague, curator Walter Sweadner, is that when populations of Karanasa were isolated from each other on separate mountains and could no longer exchange genes, they would diverge from each other over time into new entities that did not have genetic continuity between them. New species were born!” Many years after that observation, Avinoff received recognition for his findings following a posthumously published paper with Sweadner that still influences research on speciation and evolution today.

The figure of Guanyin, a deity from Chinese mythology, appears four times in the painting Frustration. Guanyin originated as a male, but appears frequently as a female, and would have appealed to Avinoff, who idealized the androgyne.

Andrey Avinoff, Frustration, 1948, Carnegie Museum of Art, Second Century Acquisition FundAt the height of World War I, Avinoff’s diplomatic responsibilities took him to the United States to secure war supplies for Russian troops. During that visit he met with fellow lepidopterists in New York City and Boston, becoming enthralled with the collections he viewed in those cities. Upon returning to his homeland, he sensed that the country he loved was on the brink of revolution. So, carrying just one suitcase that held a single album of watercolor drawings of insects and his drawing of Tibet, Avinoff left behind a collection of 80,000 butterflies, said goodbye to his native soil, and sailed off to America. An emerging émigréAvinoff was not a typical immigrant. Well-schooled in Old World manners and graces, he fluently spoke many languages, including English and French. In Russia, he counted among his friends the best dancers, artists, and writers of the time. Yet, in his new homeland, he barely supported himself as a dairy farmer in New York state, often delivering his product to market in a horse-drawn cart. He still managed to bring to America many of his relatives, including his sister, Elizabeth Shoumatoff, an excellent portraiturist who was working on the now-famous unfinished painting of President Franklin Roosevelt when he died. Tiring quickly of life on the farm during the early 1920s, Avinoff established himself as a much-in-demand commercial illustrator, thanks to an advertising executive who admired the art of Avinoff and his sister. As a result, he cut back on butterfly collecting to keep pace with his ever-increasing workload.

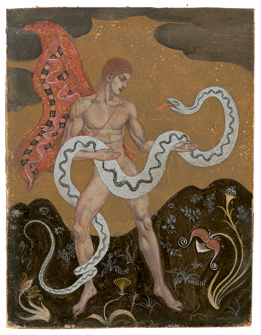

Andrey Avinoff, Cretan Motif, c. 1911–1915, Antonia Shoumatoff FosterUpon fleeing Russia in 1917, Avinoff salvaged this painting. Its allusion to Crete, a gay paradise in end-of-the-century thinking, underscores its symbolism. Avinoff’s homosexuality was the inspiration for much of his most imaginative and provocative artwork.

“Avinoff didn’t have a Ph.D. in natural history or an M.B.A. in management,” says Lippincott. “He had none of the educational background you’d expect to find in someone who holds a similar position today. He didn’t work his way up the ranks. The museum world is so much more corporate these days that you might not find Avinoff in the field now.” Despite his lack of the customary credentials, Avinoff quickly earned a reputation as a rising and enduring star in the museum world. On his watch, the Museum of Natural History acquired the Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton that serves as the holotype of that species, the single specimen officially characterizing this magnificent dinosaur. During the lean years of the Depression, Avinoff managed the unimaginable task of balancing the budget, maintaining staff levels, and financing 19 research expeditions. “His legacy as an administrator is extraordinary,” says Sam Taylor, director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. “Though he’ll never be known as a great scientist, he did produce valuable research and even more valuable collections. Just as important, Avinoff was tremendously active in public education, perhaps more so than many other previous directors. He had a weekly radio program and a lecture series at Pitt, during which he spoke about the need to appreciate nature. He introduced new techniques in the museum for the public understanding of science that used language that is almost verbatim to the kind of language we use at the museum today. In that respect, he was a pioneer and the model for the modern museum director.” Beauty in nature and sexualityThroughout his extraordinary life, Avinoff found himself cast in the roles of diplomat, scientist, artist, lecturer, administrator, and educator, to name a few. Yet only a small circle of trusted acquaintances were aware of his homosexuality, the inspiration for much of his most personal, imaginative, and provocative artwork. Even fewer people had ever viewed the homoerotic art he created. “His sexuality was more or less ignored in straight Pittsburgh society,” Lippincott notes.

Andrey Avinoff, Marshallia (Marshallia grandiflora), 1942, Wild Flowers of Western Pennsylvania and the Upper Ohio Basin“Avinoff was very prolific as an artist,” says Catherine Johnson-Roehr, curator of art, artifacts, and photographs at the Kinsey Institute for Sex, Gender, and Reproduction at Indiana University. “Most of the prints, drawings, and sketches in our collection are from his later years. But they show his skills as a draftsman and artist, including a certain ideal type for males based on models and his imagination. We did hold a small exhibit of his work, Out of Russia, but he kind of disappeared from the art world after his death. We’re excited that the Pittsburgh show is bringing him new attention.” Divided into three sections, In Pursuit of Beauty explores Avinoff’s autobiographical work, the relationship of his art and science interests, and his homoerotic creations, which the museum is subtly separating from the other sections. “Since Avinoff did keep that part of his life in the closet,” says Lippincott, “we felt that having that art separate from the other sections was appropriate. But people who view all three Remembering a beautiful mindAfter suffering a heart attack in 1945, Avinoff resigned his position at the museum and moved to New York to live with his sister. Though his health continued to deteriorate, he painted and collected butterflies as much as possible until his death in 1949.

Along with creating renewed interest in Avinoff’s art, Lippincott hopes visitors will understand and appreciate the unique and talented man behind the work. Avinoff led the Museum of Natural History for nearly 20 years during the Great Depression and World War II, from 1926 to 1945. “I think that once people spend some time with the exhibition and get a sense of what they’re seeing, they’ll get an idea of what it was like to be inside his head,” says Lippincott. “If people can see the world just a little bit the way he did, it would be a great experience. I’m not looking to break down barriers. I’m not a crusader, except for art. If you look at his art, you’ll get to know him, and if you get to know him, you’ll discover what an amazing person he was. Avinoff is someone who deserves to be known and remembered.” In His Footsteps

A guide to discovering Andrey Avinoff’s ongoing presence in the Museums of Art and Natural History, and beyond. For a full guide, visit In Pursuit of Beauty.

|

|||

Reclaiming Paul Thek · Science for Life · Setting Andy to Music · Special: Salute to David Hillenbrand · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Ragnar Kjartansson · Science & Nature: 100 Years of Homemade Lightning · Artistic License: Something to Believe In · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |

That all would change after a chance meeting in 1922 with fellow moth collector William Holland, who would invite him to join the Museum of Natural History as an associate curator of entomology, an offer Avinoff initially declined because he was still too busy supporting his family as an artist. But in 1924, he accepted the position, temporarily serving under Holland’s successor, Douglas Stewart. Two years later, he assumed the director’s role following Stewart’s sudden death. Unusual even at the time, such a meteoric rise would be nearly impossible today, says Lippincott.

That all would change after a chance meeting in 1922 with fellow moth collector William Holland, who would invite him to join the Museum of Natural History as an associate curator of entomology, an offer Avinoff initially declined because he was still too busy supporting his family as an artist. But in 1924, he accepted the position, temporarily serving under Holland’s successor, Douglas Stewart. Two years later, he assumed the director’s role following Stewart’s sudden death. Unusual even at the time, such a meteoric rise would be nearly impossible today, says Lippincott.  One of Avinoff’s earliest erotic works portrays famed Russian ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky as a faun suggestively straddling a giant hawkmoth. This combination of interest in human sexuality and lepidoptery led to Avinoff’s friendship with Alfred Kinsey, the famous sex researcher—and, yes, entomologist. Avinoff first contacted Kinsey in the late 1940s after reading his landmark book on male sexuality, and the two planned to work together on a project about creativity and sexuality. While Avinoff’s death in 1949 ended that endeavor, he did leave more than 600 pieces of art to Kinsey’s clinic, including several featured in the exhibition.

One of Avinoff’s earliest erotic works portrays famed Russian ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky as a faun suggestively straddling a giant hawkmoth. This combination of interest in human sexuality and lepidoptery led to Avinoff’s friendship with Alfred Kinsey, the famous sex researcher—and, yes, entomologist. Avinoff first contacted Kinsey in the late 1940s after reading his landmark book on male sexuality, and the two planned to work together on a project about creativity and sexuality. While Avinoff’s death in 1949 ended that endeavor, he did leave more than 600 pieces of art to Kinsey’s clinic, including several featured in the exhibition. Aside from a large exhibition of his paintings (minus the erotic work) at the Museum of Art in 1953, the art world quickly lost interest in Avinoff and his art. Other than the Kinsey Institute show, In Pursuit of Beauty is the first major exhibition devoted to Avinoff in more than half a century.

Aside from a large exhibition of his paintings (minus the erotic work) at the Museum of Art in 1953, the art world quickly lost interest in Avinoff and his art. Other than the Kinsey Institute show, In Pursuit of Beauty is the first major exhibition devoted to Avinoff in more than half a century.  Entomology display, Grand Staircase:

Entomology display, Grand Staircase:  Dinosaurs in Their Time:

Dinosaurs in Their Time:  Hall of Botany:

Hall of Botany:  Dioramas:

Dioramas:  Cathedral of Learning:

Cathedral of Learning: