Spring 2011

Spring 2011|

“We approach this project with respect, and if it’s considered by some to be controversial, we welcome the dialogue here at The Warhol.” -Eric Shiner, acting director of the warhol |

Something to Believe In

A year-long series of exhibitions at The Warhol takes the sacred texts of world religions and, through art, creates a space for dialogue about a key but often contentious marker of culture: faith.

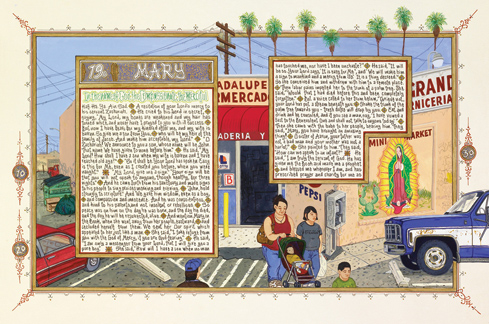

Los Angeles artist Sandow Birk is creating a cross-cultural version of the Koran, inscribing English translations on quintessentially American backgrounds.

Sandow Birk, American Qur’an Sura 29 (2), 2010, Courtesy of P•O•O•W Gallery, NY and Catherine Clark Gallery, San FranciscoGod is a metaphor for that which transcends all levels of intellectual thought,” wrote noted scholar Joseph Campbell. “It’s as simple as that.” Simple, perhaps, for Campbell, who delved deep to find commonality in the world’s myths and religious beliefs. But the issue is far more complex for most, including those contemporary artists who dare to address the subject in the fractious, suspicious, and tendentious context of today’s geopolitical fray. No better time, then, for museums to step up and create a space for reflection rather than rhetoric. That’s the aim of The Word of God, a year-long series of exhibitions organized by The Andy Warhol Museum in which contemporary artists explore the sacred texts of world religions. “Religion informs culture, but many museums won’t touch it,” says Eric Shiner, the museum’s Milton Fine Curator of Art and its acting director. “In the history of art, religion is hugely important. The Catholic Church was one of the first major patrons of art, and beauty and light were always a central concept. So we approach this project with respect, and if it’s considered by some to be controversial, we welcome the dialogue here at The Warhol.” Kicking off the series is a timely Koran-related exhibition by Los Angeles artist Sandow Birk. American Qur’an, which runs through May 1, has been described by art critics as a cross-cultural version of a fundamental book that few Westerners have read, and even fewer understand. It will be followed by Helène Aylon’s decade-long project, The Liberation of G-D, a feminist perspective on the Torah, the first five books of Moses and the foundation of Judaic law. To encourage discourse, The Warhol, which is still finalizing plans with additional contributing artists, is also organizing outreach events throughout the run of the series. Joined by the Pittsburgh Middle East Institute and the Michael Berger Gallery, which will feature some of Birk’s works in its Dis[Locating] Culture: Contemporary Islamic Art in America exhibition this April, The Warhol will host a symposium anchored by Reza Aslan on April 16. The young American Muslim author is a contributor to The Daily Beast, and has been featured on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and The Colbert Report. Shiner sees a natural fit between The Word of God and the devout upbringing of Andy Warhol, who was baptized in the Eastern Orthodox Church of St. John Chrysostom in Pittsburgh’s East End. The images of angels in Warhol’s commercial drawings, his later renderings of crosses, Easter eggs, Jesus, and the Last Supper suggest to Shiner the impact of that formative experience. “Religion was central to his life,” says Shiner. “Even in adulthood, he visited a church almost daily.” Aylon’s work has evolved against a background in stark contrast to Warhol’s. Raised in a strict Jewish Orthodox household in Brooklyn, she was married to a rabbi at age 18. But throughout her career as a conceptual and installation artist, she grew to appreciate Warhol’s work. “Andy Warhol democratized everything,” she says with a laugh. “Every single subject is fine with him, from electric chairs to God.” The choice of Aylon to follow Birk in The Word of God is, in the spirit of Warhol, equally democratic. Though both are American artists, their media and approaches differ widely. Aylon’s My Wailing Wall evokes the Western Wall of Jerusalem’s Jewish temple, with a room-sized display of Hebrew and English text highlighted in pink to draw attention to misogynistic passages. Her work Epilogue: Alone with My Mother ponders a family tradition of steadfast faith. She believes that her exploration of identity mirrors the introspection of most contemporary believers. “There’s a shame and a pride in most people about their religion,” she notes. “I am proud to be Jewish. … But I must be a feminist, too.” Birk, on the other hand, set out to create American interpretations of the complete Koran. Intrigued by Islamic culture thanks to a decade of travel to Muslim countries, the 48-year-old artist began illuminating the text of all 114 sura, or revelations, of the sacred seventh-century text, inscribing English translations on backgrounds depicting all-American scenes from stockcar racing to fishing. The project, still in progress, follows the same serial approach that the artist has previously taken in illustrated narrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy and Prisonation, a group of landscape paintings and prints depicting all of California's 33 state prisons. The Warhol show comprises more than 90 works in ink and gouache, each 16 by 24 inches. American Qur’an has raised eyebrows since Islamic believers do not consider non-Arabic versions of the text a true Koran. Although Birk interprets the traditional calligraphy and illuminations of Islam, he describes each work as a “meditation” rather than a literal illustration. “I’m interested in how text and image play off each other, as in the Dante project,” he says. Some of his enigmatic combinations, including a September 11 scene with the sura titled Smoke, have prompted controversy, but Birk says that “to the happy surprise of all,” previous exhibitions of the work have been well received. Anahita Firouz, a Pittsburgh novelist and lecturer born in Iran, agreed to serve on The Warhol’s community advisory committee for the project. Senior vice president and co-founder of the Pittsburgh Middle East Institute, Firouz is enthusiastic about the city’s opportunity to view such work. “It’s a way of educating the public—a story about the Koran with a completely different perspective. The younger generation, Muslims and non-Muslims of the 21st-century, need to know about this accessible narrative, rather than the angry one often bandied about in the media,” she says. “Birk has undertaken a serious and thoughtful work.” Shiner agrees: “We hope this series highlights the fundamental human pursuit of something to believe in.”

|

Reclaiming Paul Thek · Science for Life · Chasing Beauty · Setting Andy to Music · Special: Salute to David Hillenbrand · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Ragnar Kjartansson · Science & Nature: 100 Years of Homemade Lightning · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |