Spring 2011

Spring 2011|

“George Kaufman was the quintessential tinkerer, and Tesla was his idol.” – Mike Hennessy, program development coordinator at the Science Center |

100 Years of Homemade Lightning

Carnegie Science Center celebrates the 100th birthday of its Tesla coil and the two men whose fearless ingenuity made it possible.

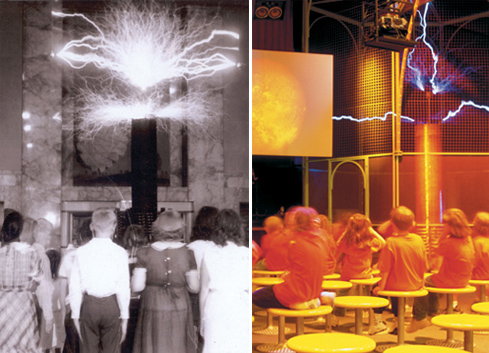

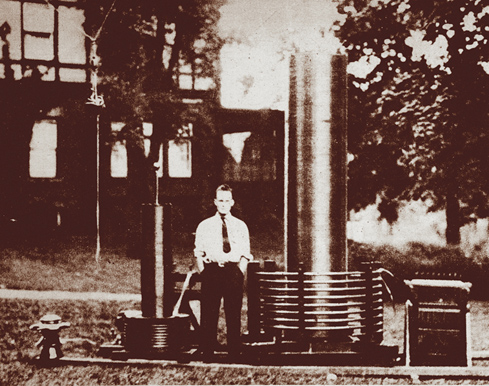

When visitors enter Carnegie Science Center’s Works Theater for its “High Voltage” show, they’re in for a tale of two inventors—and lots of homemade lightning. Seated theater-style in front of a giant steel cage, they come face-to-face with the Science Center’s prized Tesla coil, named after famed inventor Nikola Tesla, who built the first such high-voltage transformer in 1891. The visitors soon learn that this particular Tesla coil was created 30 years later by George Kaufman, who as a Pittsburgh teenager constructed it in the attic of his family’s Ben Avon home. It took him all of a year, not to mention $125 of his own money. “Kaufman was the quintessential tinkerer, and Tesla was his idol,” says Mike Hennessy, program development coordinator at the Science Center, creator and presenter of many Works Theater’s shows, and himself a big fan of Nikola Tesla. “He’s an unsung hero of science,” he says of Tesla, “and we get to keep his story alive through our Tesla coil.” Hennessy notes that Tesla’s transformer coil would go on to find applications in early radio-transmission antennae, television picture tubes, and sodium street lamps, and the inventor would later solve the problem of long-distance power distribution through another invention—the alternating current induction motor. “Together with George Westinghouse, Tesla powered the world,” Hennessy says, “and his pioneering legacy can be seen today in radios, robots, and remote controls.” It was in 1911 that Kaufman completed his own homage to Tesla —much to the chagrin of his neighbors. Seems his Tesla coil’s one million volts of ungrounded electricity would wreak havoc on the neighborhood’s power grid every time Kaufman tested it. But it more than impressed the folks at Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon University), where Kaufman would go on to earn a degree in electrical engineering. For about 30 years, the university used the Tesla coil for on-campus demonstrations.

Kaufman would eventually become the chief electrical engineer for J&L Steel, where he worked for 40 years and earned more than 100 patents. But he first tried taking his Tesla-coil show on the road, literally. Fearless and no doubt a little foolish, the young Kaufman had devised a suit made of copper cables as well as a copper headband with light bulbs attached to it. Wearing the scary-looking get up, he’d stand on top of the coil while his mother turned it on, surrounding Kaufman with bolts of electrical light and illuminating the bulbs on his head. A vaudeville show invited Kaufman to be its newest act; but after only 20 shows, Kaufman retired the copper suit because it was inflicting high-voltage burns on his body. “I was very lucky, for one mistake and I’d have been a dead turkey,” Kaufman later admitted. After that short stint in the entertainment business, Kaufman would limit his use of the Tesla coil to science-based demonstrations. In 1950, Kaufman donated his Tesla coil to the Buhl Planetarium and Institute of Popular Science, where it would often disturb television and radio reception throughout the North Side, much as it did in Kaufman’s Ben Avon neighborhood. The Tesla coil was the main attraction in the Buhl’s lobby, where it was marketed as the “man-made lightning show.” In 1991, nearly a decade after Kaufman’s death, his creation found its current home in the newly built Carnegie Science Center. “The Works Theater was designed around Kaufman’s Tesla coil,” Hennessy notes. “The coil is housed inside a special shielding cage, which contains the high- frequency interference that it generates and keeps it from interfering with other electrical devices.” This year, the Science Center will celebrate the 100th birthday of the Tesla coil with—what else?—plenty of homemade lightning bolts (or, more precisely, lightning-like plasma filaments). Hennessy says the Science Center team is particularly proud of the fact that their 10-foot-high Tesla coil is one of the country’s largest and oldest amateur-made Tesla coils still in operation. It looks a lot like a tall spool of copper thread—or 6,000 feet of tightly wrapped copper wire, to be exact. It sounds a lot like a backyard bug zapper, only about 1,000-times louder. And at 100 years old, it requires plenty of tender loving care, most of that coming from the Science Center’s Rich Kwiatkowski, another scientific tinkerer who has cared for the Tesla coil since its days at the Buhl Planetarium. Kwiatkowski is the Science Center’s—and, before that, the Buhl’s—manager of exhibits maintenance. “He’s our electrical guru,” Hennessy boasts. “Some of the most thrilling times I’ve had here have been while working with Rich in the cage with the coil!” Almost daily, Science Center presenters proudly regale visitors with stories of Nikola Tesla and George Kaufman during the “High Voltage” show. They also use their century-old Tesla coil for some “high-drama” shows, including a Frankenstein demonstration at Halloween. “It’s great for special effects!” Hennessy proclaims proudly, something George Kaufman, the short-lived showman, would surely appreciate. Visitors can catch the Tesla coil in action most weekdays in the Works Theater. |

Reclaiming Paul Thek · Science for Life · Chasing Beauty · Setting Andy to Music · Special: Salute to David Hillenbrand · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Ragnar Kjartansson · Artistic License: Something to Believe In · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |