|

||||

|

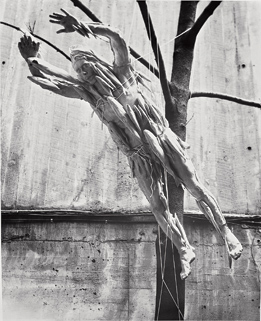

Header: Paul Thek, Untitled (Diver) detail, 1969–1970, Collection of Gail and Tony Ganz

|

Reclaiming Paul Thek

Carnegie Museum of Art partners with the Whitney Museum of American Art to present the first major American retrospective of Paul Thek, an artist who remains relatively unknown, but whose work is more relevant than ever. In the late 1960s, artist Paul Thek rented a small white house on the Italian fishermen’s island of Ponza; it included three rooms, a gas-burning stove, and a landlady who would bring him wine and figs. Every morning, he’d sail toward nearby caves until he reached waters clear enough to see mountains well below the surface, and schools of fish squeezing into dark crevices. “The edge of the boat was five feet high, so we’d pull ourselves up to watch Paul, who was lean and gorgeous, dive into his joy,” recalls Ann Wilson, an artist, collaborator, and confidant who traveled with him in Europe. “It was pure magic.” Thek captures the transcendent spirit of his art in the painting Untitled (Diver) that depicts a lone swimmer, beautifully taut, penetrating blue and white strokes on aging newsprint. Paradoxically, the figure also hangs still, if not limp, his feet oddly cut off at the brown paper’s edge, so that he looks both arrested and in motion, plumbing the water that seems to halt him. It’s an apt image that serves as a title for the artist’s first major American retrospective—on view at Carnegie Museum of Art through May 1—reflecting a deep and daring search for meaning that infused Thek’s art, and a life filled with contradiction.

Paul Thek paints a self-portrait in his studio in 1967. In the foreground is a life-sized wax sculpture he created of himself that would later be dubbed the “Hippie” and serve as centerpiece of his iconic—and now lost—installation, The Tomb.On one hand, Thek used non-archival materials such as newspaper, latex, tissues, and sand to build mammoth, ephemeral installations. On the other, he built tombs and airtight Plexiglas vitrines, reliquaries that preserved cast replicas of himself and severed body parts like sacred objects. He rejected the commercialism of the American art world, but longed for inclusion in its canon. He was connected to his Catholic upbringing, and reflected its imagery and theology in his work. He was also gay, and deeply social, writing in his journals that God made him to love men, and of an immorality in monogamy. “How do you deal with work that isn’t there? We decided not to reconstruct anything. Death and decay was built into his art, so we had to embrace it.”-Lynn Zelevansky, co-curator of DiverThek died of complications from AIDS in 1988. He was 54 and living in New York where the art world had cast him aside—partially by his own making—after a prolific career producing a brave and idiosyncratic aesthetic that foreshadowed decades of contemporary art that succeeded him. He was one of the first artists to create environments or installations. Yet he somehow fell through the cracks of art history, says Lynn Zelevansky, The Henry J. Heinz II Director of Carnegie Museum of Art and co-curator of Paul Thek: Diver, along with Elisabeth Sussman, the Sondra Gilman Curator of Photography at the Whitney Museum of American Art, where the show premiered last fall. “His work was incredibly daring, and influential, but it wasn’t au courant, so he became a sort of cult figure,” says Zelevansky. “He became someone many artists looked to, but didn’t really know. It may be an oversimplification to say that he was forgotten. But I think he was definitely eclipsed. He is still relatively unknown.” An island unto himselfAccounts of Thek describe an unforgettable man: handsome, sassy, and smart, with a sense of humor that permeated his work and life. He depicted himself as the Pied Piper, and also as a hot potato. Thek’s visit to the Palermo Catacombs in Sicily moved him, and moved his art in new directions. There, he saw thousands of corpses in rows, a site that made him feel, “strangely relieved and free. …We accept our thing-ness intellectually, but the emotional acceptance of it can be a joy.” .jpg) Thek's “Meat Pieces” resemble glistening pieces of raw flesh. A number of these works—made of beeswax, covered with fluorescent paints, and enclosed in Plexiglas boxes—are on view in Diver. Thek's “Meat Pieces” resemble glistening pieces of raw flesh. A number of these works—made of beeswax, covered with fluorescent paints, and enclosed in Plexiglas boxes—are on view in Diver.Paul Thek, Untitled (Meat Piece with Flies), 1965, from the series Technological Reliquaries, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The Judith Rothschild Foundation

|

|||

|

|

He “approached the trash heap of 1960s counterculture a little too closely … which is the reason [he was] made to disappear, dealt a critical death blow,” artist Mike Kelley wrote in the catalogue for one of Thek’s first posthumous exhibitions abroad. Kelley’s own performance-based collaborations and installations invoke Thek’s installations from later years. “Unfortunately, Thek is literally deceased. He’s not around to argue his place in history or set the record straight.”

Diver, the first real attempt to do just that, took root five years ago while Zelevansky was serving as curator and head of contemporary art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. She and Sussman journeyed across two continents to survey vast collections, including the largest, housed in the Kolumba Art Museum in Cologne, Germany.

Their research relied heavily on many first-person interviews that had yet to be networked into a collective memory. “There were still quite a few people left who knew Thek and worked with him, but we also knew that this wouldn’t be the case forever,” Zelevansky says. “So the important thing was to capture, as much as we could, the recollections of those who really knew him.” The exhibition catalogue includes letters Thek sent to Wilson over the years and curator Michael Nickel’s personal account of Thek’s novel attempts to salvage damaged works by rebuilding them during the run of a show.

Zelevansky finds special relevance in hosting this exhibition at Carnegie Museum of Art. Thek’s work has been included in two Carnegie Internationals, the first in 1967. Most recently, curator Douglas Fogle prefaced Life on Mars, the 2008 Carnegie International, with Thek’s Earth Drawing I, a floating orb on newsprint that captured his organizing premise—what would aliens in space learn of our world when viewed through the lens of contemporary artistic practice? His work is “a collective self-portrait of humanity colliding with the quotidian grind of daily existence,” Fogle wrote. A reminder that “we are profoundly alone but paradoxically together.”

In the opening gallery, an Andy Warhol Screen Test, filmed in 1964, shows a young and handsome Paul Thek.

Photo: Stan Franzos

Diver also marks the museum’s renewed commitment to promoting an active and compelling contemporary art program that moves beyond the International, and emphasizes collaboration with institutions of similar size and purview, such as the Whitney. “Pittsburgh has an aging collector base,” Zelevansky says. “We need new, younger collectors who need to see more contemporary art, more often. We also should be collaborating so that our exhibitions tour, which means our accomplishments and contributions as a museum are out there in the world for people to see.”

An artists’ artist

Thek’s move to Europe allowed him to escape the commercial and political environment and high-priced living of New York, providing freedom to make the art of his choosing. He also began to live even more communally by hosting other artists and inviting them to contribute to his museum-commissioned installations. Thek’s crew was usually given a month to build a work; they slept, ate dinner, and drank wine in the gallery—liberal access unheard of in the United States at the time, and certainly prohibited today. Collaboration became key to his process.

“Paul was one of the only men at the time to allow a woman artist to predominantly contribute to his images,” Wilson says. “I was working with nature and wasn’t working with physicality as he was. But we’d see the same things in a painting. When he was invited to make his first installation in Stockholm, he said to me, ‘Please come to Stockholm. You can make anything you like.’”

“Paul was one of the only men at the time to allow a woman artist to predominantly contribute to his images,” Wilson says. “I was working with nature and wasn’t working with physicality as he was. But we’d see the same things in a painting. When he was invited to make his first installation in Stockholm, he said to me, ‘Please come to Stockholm. You can make anything you like.’”

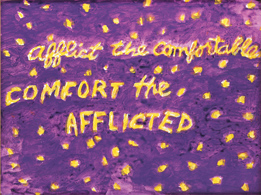

Paul Thek, Afflict the Comfortable, Comfort the Afflicted, c. 1985, Collection of Gail and Tony Ganz

© The Estate of George Paul Thek, courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

Wilson, along with other members of The Artist’s Co-op (as Thek’s collaborators came to be known), traveled with him to Moderna Museet, which back then was housed in an old naval academy drill hall on Skeppsholmen Island, accessible only by crossing a small bridge that was flanked by two sculptures of naked men. Thek’s installation was equally mythical. The group built a large pyramid with a bare plywood frame covered in newsprint, resting on a sea of sand, and surrounded by candles. Visitors would climb a rickety ramp, with tall tree limbs as posts, to enter the low-lit floating arc. Inside was a table for two, pasted wet drawings, hung tissues, a single lamp, and old clothing on a line. Outside, there was a deer in a boat nestled in trees, and a navigation map projected on the wall.

“I’d just come from Fire Island [another one of Thek’s beach retreats], where I saw a doe and her baby come up over the sand dune,” Wilson remembers. “Then I went nuts in Stockholm when I found all of these stuffed animals at the natural history museum there, including a great stag, and the most beautiful albatross. I also found the little mangy rowboat on the waterfront, which looked like the peeling of time. So I brought them back and built the piece.”

“He became someone many artists looked to, but didn’t really know. It may be an oversimplification to say that he was forgotten. But I think he was definitely eclipsed.”

-Lynn Zelevansky

These new installations reflected Thek’s growing interest in rituals—as well as a retreat from making saleable objects. He celebrated time passing by enacting the past: For A Procession/Easter in a Pear Tree, which took place in the Dutch countryside, he carried a large, wooden cross across his back and hung it in a tree. In another performance, he paid homage to death by holding a taxidermied buzzard over his head while standing naked on graceful tiptoes. He believed that art shouldn’t have a shelf life of more than 10 years; like life, art was meant to decay.

“He had a phenomenological approach to things, and for a long time he would say that if you weren’t there for it, then you missed it,” says Zelevansky, which poses problems in trying to organize an exhibition that accurately reflects the breadth of his work. “How do you deal with work that isn’t there? We decided not to reconstruct anything. Death and decay was built into his art, so we had to embrace it.”

Diver does include a diverse sample of his work, nearly 150 pieces in all, such as the “Meat Pieces” and other wax works; his small bronzes produced in Rome; headpieces; and newspaper paintings that mark not just stages of his career, but the evolution of his psychological state that begins with bravado and ends with a keen sensitivity to the human experience, particularly notions of ephemerality and time. A cast of Fishman is tied to the underbelly of a table hung from the ceiling. Dozens of journals are also on display, as well as ample documentation of The Tomb, and Thek in his studio, as photographed by his lover Peter Hujar.

This first retrospective will likely be the last, says Zelevansky. It won’t be easy to transport, treat, and re-install many of the existing works so ambitiously. “The work is fragile; collectors will be less and less willing to lend. Eventually it will disappear,” she says.

This first retrospective will likely be the last, says Zelevansky. It won’t be easy to transport, treat, and re-install many of the existing works so ambitiously. “The work is fragile; collectors will be less and less willing to lend. Eventually it will disappear,” she says.

Lynn Zelevansky discusses Warrior’s Arm, created by Paul Thek in 1967, during Diver’s opening event.

By 1973, Thek was looking for ways to return to the States; in late 1976 he came back, perhaps due in part to fading opportunities in Europe, and in preparation for a new installation of his work in Philadelphia. “The whole time he was abroad, he still sought recognition in the U.S.,” says Zelevansky, noting that’s one of the reasons this exhibition is important. “He really wanted to be acknowledged at home.”

Time is a river

In 1976, Thek returned to his hometown of New York to an art world where, to his surprise, he was largely unknown. Soon after, his health deteriorated, and so did his finances. He took up odd jobs, lost friends, and wasn’t able to find gallery representation.

“There were experimental treatments for AIDS available at the time, but Paul couldn’t afford it,” Wilson says. “He would spend the stipends he received from the museums in Europe on the installations, and then he divided the rest of it among us. There was just never enough money. We had to produce [a few new artworks] just to get airfare to come back. But he was a hero in Europe.”

Thek wanted acknowledgement of his contributions, but was never very good about collecting it. Wilson remembers when Thek invited the art historians Diane Kelsner and Alan Rosenbaum to his island in Ponza, and then left them stranded on rocks in the middle of the ocean when they tried to interview him.

.jpg) Once back in the United States, he made new paintings, again on newsprint, but with a serenity that he lacked in other aspects of his life. These were washes of color, bearing childlike and profound phrases that one could live by if you can get over the heartbreaking sentiment: “Afflict the comfortable, comfort the afflicted”; “While there is time, let’s go out and feel everything”; “Dust”; “Time is a river”; and “Philosophy of convenience.”

Once back in the United States, he made new paintings, again on newsprint, but with a serenity that he lacked in other aspects of his life. These were washes of color, bearing childlike and profound phrases that one could live by if you can get over the heartbreaking sentiment: “Afflict the comfortable, comfort the afflicted”; “While there is time, let’s go out and feel everything”; “Dust”; “Time is a river”; and “Philosophy of convenience.”

Paul Thek, Untitled (Chair with Crow and Meat), 1968 © The Estate of George Paul Thek, courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

Photo: © Kolumba, Köln/Lothar Schepf

In his final exhibition, he hung many of theses works low to the ground, so that the blue-hued paintings created a “pool” around the viewer. Unlike his “Meat Pieces” that stand tall and proud at the entrance of Diver, these works are lyrical ruminations, showing a retreat into his art and mind, if not the church, during his last years.

“It’s hard to say what he’d be doing now if he hadn’t died,” Zelevansky says. “He had so many psychological issues. But he was very, very sensitive to the culture around him. He was such an iconoclast, and also believed that there had to be humor in life.”

Science for Life · Chasing Beauty · Setting Andy to Music · Special: Salute to David Hillenbrand · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Ragnar Kjartansson · Science & Nature: 100 Years of Homemade Lightning · Artistic License: Something to Believe In · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |