Back

It started with a woman known for her bright personality,

a last name of (not surprisingly) Sun, and the nickname “Peachblossom.” It

originally involved six people and now involves millions.

What is this phenomenon? It’s the relationship between

Carnegie Museum of Natural History and the Shanghai Science

and Technology Museum (SSTM). And it’s only just

beginning.

Situated in the financial district of China’s

largest city, SSTM opened in 2001 in a multi-million-dollar

complex

the size of 13 football fields. It features two IMAX theaters,

six exhibition halls, and a natural history wing culled

from the older Shanghai Natural History Museum.

Known as

a “palace of science,” SSTM serves

China’s national plan to revitalize the country through

education and science. But after receiving massive crowds

during opening months, it has experienced a dip in attendance

and turned to other

museums for ideas.

Carnegie Museum of Natural History is

one such museum, attracting SSTM’s attention for

its renowned science, exhibitions, and education programs.

Responsible for the

initial contact was the museum’s library manager,

Xianghua “Peachblossom” Sun, who moved to Pittsburgh

in 1989 as part of an international scholars program that

connected museums around the world. Sun grew up in China

and worked for the Shanghai Museum of Natural History for

17 years.

“

Shanghai and Pittsburgh are the two places I call home,” says

Sun, who goes by the colorful nickname Peachblossom, a

title earned while eating lunch outside the museum one

sunny, spring day. “People appreciated my cheery

disposition, and the nickname stuck,” she explains. “I

even sign interoffice emails with the initials PB.”

When

Sun found out SSTM was seeking a partner with which to

exchange information, she convinced then-Deputy Director

Sylvia Keller to arrange a visit from six Shanghai representatives.

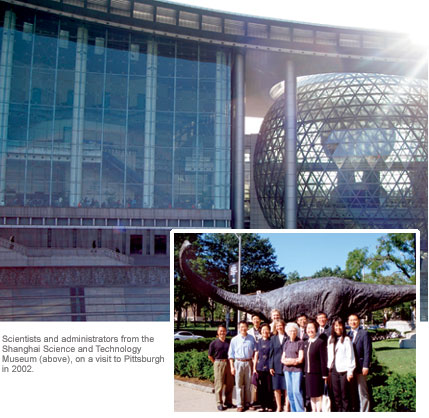

Arriving the summer of 2002, the group of scientists and

administrators

spent two weeks learning about the Museum of Natural History’s

mission and structure, while also getting a bird’s-eye-view

of its education programs. “They were full of questions

about how to build a successful natural history wing,” recalls

Sun, who served as a translator during the visit. “And

they learned from us that it takes more than an expensive

building and a lot of money; it takes years of research,

a strong collection, and focused audiences.”

The first

visit proved so fruitful that it set off a series of other

visits and laid the foundation for a long-term

relationship. The next exchange came the following year,

when Keller, Sun, Museum Director Bill DeWalt, and Chair

of Exhibits Jim Senior spent a week in Shanghai viewing

SSTM’s facilities and delivering formal presentations

about the Pittsburgh museum’s administrative structure

and educational programming. “They were particularly

impressed with our outreach programs to schools and the

community in general,” says DeWalt. “Like many

science museums, they face the challenge of attracting

repeat visitors because their exhibits rarely change. We

helped them realize how museum education programs can serve

the public and drive attendance.”

Between meetings,

DeWalt and his colleagues also toured Shanghai’s

older Natural History Museum, where Sun once worked. Despite

losing staff members and part of its

collection to SSTM, the museum remains open to the public.

“

Shanghai Natural History Museum is in poor condition,” laments

Sun. “We saw specimens in jars that were colorless,

exhibits that were outdated, and a huge shortage of people

staffing the facility.”

Opened in 1956 and located

in an older part of Shanghai, the Natural History Museum

looks unlike the modern museums

cropping up throughout the city. In an effort to update

the facility and become a world-class natural history museum—one

that surpasses the natural history wing of SSTM—scientists

and administrators are seeking government support for a

new building. They hope to equip it with state-of-the-art

exhibitions and programs in science and education.

“

The prospect of a new natural history museum in Shanghai

means a lot to us,” says DeWalt. “It could

open the door to more partnerships in science and collaborative

exhibitions.”

Until then, DeWalt explains, the collaboration

will stay focused on education, a high priority for both

SSTM and

Carnegie Museum of Natural History. A week-long visit in

October 2005 centered on this goal and involved Education

Chair Diane Gryzbek and Education Specialist Pat McShea,

who traveled to Shanghai by special invitation to provide

an overview of their division’s structure and financial

plan.

“

They wanted to know the nitty-gritty of how we run and

manage our programs,” says Grzybek. “We spent

an entire day talking about admission fees, rates for school

groups, endowments, donors, and relationships with corporations.”

Like

other government-sponsored cultural organizations in China,

SSTM wants to learn more about diversifying funding

sources and building programs that sustain themselves with

admission fees. This endeavor comes at a time of rapid

industrialization and financial growth in China, during

which the centrally-planned economy is starting to shift

to more of a market economy. Says Jin Xingbao, deputy director

of the Shanghai Museum: “The collaboration with Carnegie

Museum of Natural History helps us realize the crucial

role of education and how we can use it efficiently. Our

programs are a great marketing tool and an indispensable

part of our museum branding.”

To Sun, whose family

and friends still live in Shanghai, Jin’s words are

a dream come true. “The current

focus on education offers an invaluable service to my homeland,” she

says. “Few Chinese people attend university, but

many are hungry for knowledge. This is a perfect way to

satisfy their hunger.”

Back

| Top |