Back

As Real As It

Gets

A

new exhibit at Carnegie Museum of Natural History pulls

out

all the stops to show us just how far we’ve come

in the art of taxidermy—including a famous white

rhino, an albino squirrel, and the “death mask” of

George the gorilla. By

Christine H. O’Toole

The Denmon girls are little sisters from the city. The buffalo’s

a beefy guy from the plains. At their first encounter at Carnegie

Museum of Natural History, all three stood stock-still.

What drew Noa, age 10, and Drue, age 8, to the buffalo’s

side on a Sunday visit was the stuffed creature’s inviting

plush pelt. As they circled the specimen, plunging their fists

into its fur, Drue tilted back her head and looked up admiringly

at the animal’s gentle dark eyes, trying to explain the

attraction.

“

It feels like it could get...alive,” she said intently.

That

first-person experience, closer than any zoo would allow,

is the peculiar fascination celebrated in Stuffed Animals:

The Art and Science of Taxidermy, which opened in the Hall

of Sculpture May 21. With its examples of the ultra-realistic

specimens and dioramas created to give city dwellers a

glimpse of the natural world, the exhibit examines the flip

side

of Carnegie Museum of Art’s current exhibition Fierce

Friends.

Designed by Carnegie Museum of Natural History staff,

Stuffed Animals is the first American examination of the

evolution

of taxidermy, the heart of most American natural history

collections, in at least three decades. The museum’s

110-year-old collection is anchored by some of the finest

re-creations of

animals and animal groups in the world.

Almost the Real Thing

Generations of Pittsburgh children have been thrilled by Jules

Verreaux’s bloodthirsty “Arab Courier Attacked

by Lions,” in which a camel rider fights off a pair

of Barbary lions with scimitar and rifle. One of those enthralled

kids still visits the diorama regularly: Darnell Warren,

who grew up to become an artist and instructor at Carnegie

Museum of Art himself.

“

It’s got such dramatic appeal, and the extinct lions

have historic significance,” Warren professes. “And

there’s a wonderful narrative behind what’s going

on. As a kid, it started my thought process: Would the man

survive? Who would win?”

Warren now brings his drawing

students here to learn from the skills on display inside

the large glass case: artistic

composition

on a grand scale.

“

Taxidermy involves sculpture and anatomy and realism,” says

Steve Rogers, the museum’s long-time collection head

for birds, reptiles, and amphibians, and a taxidermist

himself. “And

when you add a background painting in the dioramas, it’s

the whole package. It’s as complete as you can get.”

The

summer exhibit won’t include the Denmon sisters’ new

best friend, or the Verreaux display, both of which are

on permanent exhibit upstairs. But it will include other

rare

and dramatic mounted specimens—from a pair of rhinos

to massive big-game heads to a famous local gorilla selected

from thousands in the Museum of Natural History’s

scientific collections.

Today’s museum visitors,

accustomed to finding video images of wild animals with

a few clicks on Google, might not

realize the leaps of imagination taken by early taxidermists.

“

A hundred years ago, you’d get a package with a dried

hide, folded and salted, and a few leg bones. Then, you’d

have to figure out what it looked like,” explains

Rogers. Needless to say, that led to some inaccuracies. “With

no muscle definition, the results in minor museums might

look like a stuffed animal on a kid’s bed. They didn’t

look real, because the creators weren’t sculptors.” Through

luck and circumstance, the Museum of Natural History created

its first taxidermy collections with the help of

some early masters of the craft. Rogers, who has traced

the history

of American taxidermy, points to three masters—Frederic

Webster and Remi and Joseph Santens—who set world-class

artistic standards at the museum at the turn of the 20th

century.

Filling an Empty Museum

When he joined the museum in 1897, two years after its

founding by Andrew Carnegie, Frederic Webster was one

of the country’s

leading taxidermists. His closest friends and colleagues,

who were collection heads of the new National and American

Museums

of Natural History, would become his rivals in procuring

the most sensational specimens for America’s empty

museums.

It was a seller’s market, and prices were

steep. And Andrew Carnegie, who purchased some of Webster’s

first acquisitions, understood that the principle of supply

and demand

applied to stuffed animals, too. “Crocodiles are

snapped up as offered, while dugongs bring large prices,” he

quipped in an 1884 book. “What is pig metal to

this?”

The museum seized the chance to acquire the “Arab

Courier” in

about 1898 for $25. In the same era, it received hundreds

of rare specimens from the Good family, a missionary

family in

Gabon and Cameroun with connections to then Carnegie

Museum Director William Holland, a Presbyterian minister.

(A Good

family descendant, anthropology section head Dave Watters,

now works at the museum.) One of those mounts, a gorilla,

will be displayed in Stuffed Animals.

Return of the White Rhino

Another major early purchase was a white rhinoceros, then nearly

extinct. When the museum bought the beast in 1901, it was an

international coup, the stuff of blockbuster exhibits: one

of only four such mounts in the world and the only one on display

in North America.

A decade later, the white rhino was still

rare enough to make Teddy Roosevelt drop his monocle. “Holland,

where did you get that specimen?” he demanded in a 1912

visit. “I

am astonished at seeing it.” A decade later, the white rhino was still

rare enough to make Teddy Roosevelt drop his monocle. “Holland,

where did you get that specimen?” he demanded in a 1912

visit. “I

am astonished at seeing it.”

Stuffed Animals pairs the

white rhino with a later museum re-creation: a black rhino

bagged by Pittsburgher Childs Frick on safari

in 1909. The comparison illustrates how Carnegie Museum experts

vastly improved the realism of their mounts. The white rhino’s

creators, the British firm of Gerrard and Son, had likely

never seen a live one. They relied on a rickety wooden frame

and

wood shavings to approximate its shape. The later mount,

created in 1920 by Remi Santens, used a meticulously molded

plaster

form to simulate muscles under a thinner hide.

The pair was

exhibited together for seven decades and will be reunited

in Stuffed Animals. Two other magnificent Santens

creations, the jaguar family diorama and the 12-foot giraffe,

still command attention in the museum’s second-floor

Hall of African Mammals exhibit of spectacular dioramas. Always popular with hunters (even early Native Americans

mounted animals), taxidermy became enormously popular with

adults and

youngsters during the beginning of the 20th century. One

mail-order course enrolled over 35,000 amateurs. The museum’s

new exhibit includes the work of one of them, an ambitious

10-year-old

named Rush Davis.

Davis was convinced that the rare creature

he’d found

and mounted—an albino grey squirrel—was worthy

of a spot in Carnegie Museum’s collection. In his

first correspondence with the museum in 1904, he boldly

named his

price—$25—which museum Director Holland briskly

deemed “excessive.” After bombarding Holland

with several more letters, Davis finally received $7.50

for his

work. Hunter and Conservationist

Another student in the museum’s mail-order course was

Teddy Roosevelt, whose enthusiasm for wildlife led him to found

the Boone & Crockett Club (B&P) in 1887. (He also presented

the museum with a black rhino, shot shortly before his visit

here. A fiberglass copy of it stands in the Hall of African

Wildlife.)

The B&C Club preached “fair chase” hunting

ethics, as well as keeping records on the biggest trophies

shot and mounted by its members. Carnegie Museums stored

some of those prize winners until the early 1990s. A

massive moose

head from the club, its rack measuring 68 inches from tip

to tip, crowns the Stuffed Animals exhibit and commemorates

the

big-game era. Now headquartered in Montana, the Boone & Crockett

club still exists, supporting sustainability and conservation.

Conservationists

of the 21st century are far less likely to be the wealthy

big-game hunters of the past, or the hunter-gatherers

of the African savannah.

But they recognize that recreational hunters also care for the environment.

“

People who hunt for recreation often feel strongly about the conservation

of species. Through revenue they provide from licenses and their interest

in the

preservation of habitats, they may be contributing to the overall well-being

of animals,” notes museum Director Bill DeWalt.

But not all of

the animals mounted for the museum’s collection were hunted;

some died of natural causes.

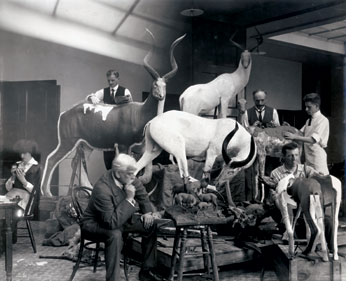

Carnegie

Museum Director William Holland (seated at left) observes

as his staff works its magic. Carnegie

Museum Director William Holland (seated at left) observes

as his staff works its magic.

The museum has accepted specimens from

the Pittsburgh Zoo since its founding in 1898. When George the

gorilla, a longtime resident, died

in 1979,

the museum modeled his facial features through essentially the

same kind of

death mask

sculptors use to capture human bone structure, muscles and wrinkles.

The mask helped museum staffers re-create the fleshy contours in

the final

mount, used

later in a diorama. In Stuffed Animals, George’s mask is

included to illuminate one of the museum’s earlier

efforts: the 1899 mount of an African gorilla from the

Good missionary family. Comparison

of the two make glaringly clear how early

taxidermists wrestled with the issue of reproducing the indentations

and curves of their subjects’ faces. (Visitors touring Fierce

Friends this summer at the Museum of Art will find the 1899 gorilla’s

skeleton on display there, accenting the connection between science

and art.)

The buffalo, the Denmon sisters’ please-touch

favorite in the Hall of American Indians, came to the

museum after a long

life, with the blessing of

Native Americans. After a full religious ceremony performed by

Rosalie Little Thunder, complete with burning sagebrush and prayers,

the animal was put down

in 1998 and went on display shortly thereafter.

Interest in conservation

and animal habitats began to broaden to city dwellers

as the 20th century progressed. The museum complemented

its

large-scale

dioramas with smaller animals to introduce Pittsburghers to

local residents. “

The settings perfectly replicated real habitats, and the emphasis

shifted from single creatures to natural family groups,” explains

Rogers. He adds that Frederic Webster, a perfectionist, insisted

on high fidelity. He re-created

the habitat of golden-winged warblers by locating a sheltered

nest, then removed two surrounding square feet of natural

materials intact so he could replicate

its details.

Sometimes the insistence on minute detail demanded

armies of volunteers to work alongside taxidermists and

muralists. For

the Alaskan moose

diorama, mounted in 1970, a committee of women volunteers

donated 1,100 hours

to create

perfect

faux leaves for its alders (2,000 leaves), willow (1,800),

and cranberry (3,200 for one bush). The fox, possum, and

owl families

displayed

in Stuffed Animals

match that level of realism.

“

Dioramas can really provide an accurate depiction of biological diversity,” says

Bill DeWalt. “Even in a zoo, there’s no way to get as close to

animals as you can get to a diorama. And in a zoo, you’re looking at

them in a habitat that is not their own.

“

There was a time in which dioramas fell out of favor in museums because they

were static,” admits DeWalt, “but major museums have invested substantially

in conserving and improving spectacular dioramas.

“

Our perspective here is to make the dioramas come alive by adding touchables

and touch screens, making them a more interactive exhibit,” he adds. “A

computer screen that tells you what animals ate, or how many existed, helps

the animal come wonderfully to life. They have so much more to tell us.”

Back | Top |