Back

For the past six months, Carnegie Museum of Natural

History’s

most famous residents—Diplodocus carnegii, Apatosaurus

louisae, Allosaurus fragilis, Protoceratops andrewsi, and

Tyrannosaurus rex —have been getting badly needed

makeovers in the New Jersey studios of master dinosaur

preparator Phil Fraley. Their bones are being cleaned and

preserved, then they’ll be reassembled

in dynamic, scientifically accurate poses before being disassembled,

again, for their return to Pittsburgh.

Soon, Carnegie’s

famous five will be joined by three lesser-known dinosaurs

that for decades hung encased in

ancient rock and plaster on the walls of the museum’s

Dinosaur Hall. But first, museum fossil preparators must

complete the arduous work of freeing the well-preserved

skeletons—some of the best-preserved of

their respective species ever found—from stubborn

rock that, at times, seems unwilling to release them.

Their names are Camptosaurus, Dryosaurus, and Corythosaurus,

and when Dinosaurs in Their World opens in late-2007,

they’ll

be standing again for the first time in millions of years.

Camptosaurus and Dryosaurus, both unearthed in the early

1900s during Carnegie digs in Utah, will permanently

reside in displays dedicated to the Late Jurassic period

(159-144 million years ago). Corythosaurus, obtained

as part of

an exchange with the Royal Ontario Museum in 1940, will

be placed beside other creatures from the Late Cretaceous

period (99-65 million years ago).

“

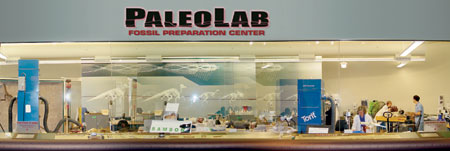

It’s really amazing when you think about it,” says

Matt Lamanna, the museum’s assistant curator of

Vertebrate Paleontology and chief dinosaur researcher. “We’re

removing the remains of these dinosaurs from the rock

they died in millions of years ago—some of it in

PaleoLab, in full view of our visitors.”

The people

doing the work are Paleontology Laboratory Manager Allen

Shaw and Scientific Preparators Dan Pickering,

Alan

Tabrum, Yvonne Wilson, and Norm Wuerthele. In her journal

entries documenting her early work on Camptosaurus, published

on Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s

website (www.carnegiemnh.org), Wilson likens the process—the

chiseling, the chipping, the drilling—to “trying

to wear away a mountain with a dress pin.”

And

there’s more where that came from. A lot more.

Following

are some slices of life from PaleoLab over a six-month

period in 2005, courtesy of Wilson, who has

spent

many long days with Camptosaurus. And, yes, a year

later, her work continues.

|

| Journal Entries: From Yvonne Wilson |

January 13, 2005, 5:20 PM (first entry)

We have taken the Camptosaurus that has been in Dinosaur Hall since 1925 and

moved it into PaleoLab. The skeleton is mounted into a wall panel. Instead

of rock, it is largely encased now in plaster. Our goal is to free the fossil

in order to make a freestanding, mounted dinosaur. And this is the start of

it. We have taken the Camptosaurus that has been in Dinosaur Hall since 1925 and

moved it into PaleoLab. The skeleton is mounted into a wall panel. Instead

of rock, it is largely encased now in plaster. Our goal is to free the fossil

in order to make a freestanding, mounted dinosaur. And this is the start of

it.

There is still

original rock, or matrix, surrounding the torso.

This rock, from the Morrison Formation (in

Utah), is known to be extremely hard, sometimes

harder

than cement. That could be part of the reason the original workers left this

specimen mostly embedded in the rock. Another reason, though, is that it

is nicely

articulated (meaning, the bones are still in the same place as they were

in the body). I can only hope it will cooperate.

January 28, 2005,

4:19 PM January 28, 2005,

4:19 PM

Our dinosaur curator, Matt Lamanna, asked us

to check out the quality of the bone on the "underside" of

the specimen. He wanted to make sure the fossil

would hold up once it is taken out of the rock.

We opened up the

back fully. This is the "jacket," or

the plaster and burlap package in which paleontologists

wrap their fossils in order to

ship them

home from the field. There is a large board supporting the back of the jacket.

Hey, what is this?

They left us a message in a bottle!

The workers

who put the exhibit together left a note saying

where and when the specimen was

found (northeastern Utah, 1922), and who worked

on the mounting

project in 1925. In a second

handwritten message, there is a notation that the exhibit was taken down

and "lighted" in

1934.

March 30, 2005,

11:20 AM March 30, 2005,

11:20 AM

Just looks like a hunk of rock now. Yet a dinosaur

lurks beneath.

I attack the rock

lump with hammer and chisel. On rock this hard

(arrrg!),

this method is

much faster than an airscribe—though

I still feel like I am trying to wear away

a mountain with a dress pin.April 6, 2005,

11:42 AM

… My arms ache with the effort at the end of the day, and I can feel the

ringing of the chisel in my hand even after I stop to take a break. … My arms ache with the effort at the end of the day, and I can feel the

ringing of the chisel in my hand even after I stop to take a break.

May 21,

2005, 1:17 PM May 21,

2005, 1:17 PM

As I work along the spinal column, I am finding things that are both lovely

and awful at the same time—ossified tendons. These are mineralized

tendons that helped stiffen the backbone and support the tail of the

dinosaur. They

are frequently found in ornithopod dinosaurs (ornithopods include dinosaurs

such

as Iguanodon, Hadrosaurus, and my Camptosaurus). I am consulting with

other preparators to see if I can save these slender tendons.

June 5, 2005, 6:34

PM June 5, 2005, 6:34

PM

I have been isolated with this fossil in sensory-depriving

mask, goggles, bandana, earplugs, and earphones.

One ends up in a "zone" where the

fossil becomes the only thing in the world

with you. In this mode, I have unearthed

most of

the ribs.

The whole beast

looks like a side of beef these days.

After

I free the ribs from the spinal column, my

plan is to roll the jacket so that I can

attack the vertebrae from the opposite side.

|

|

Back

| Top |