Back

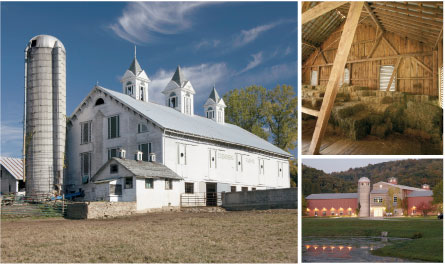

Western Pennsylvania is still

home to more than 25,000 barns, each with a personality

and history all its own.

Photos: Tom Little

The

trappings of power and influence are as diverse as

the people who seek to display them. For some, they are

the

stuff of cool sports cars or hot trendy wardrobes.

But for others, they are realized in things as simple—and

complex—as

barns. Yes, those structures that continue to illuminate

the western Pennsylvania landscape have long stood

as status symbols.

“

Historically,” says independent scholar Lu Donnelly, “many

farmers would live in less-than-perfect houses while

their barns were perfect.” Well-built, well-maintained

barns were seen as a reflection of the owner’s

pride and prosperity. “People revered them,” asserts

Donnelly. And although the functionality and practicality

of barns has changed over time, their power to engage

the imagination and summon a sense of romance has

not. It is

in this spirit that Carnegie Museum of Art’s

Heinz Architectural Center presents Barns of

Western Pennsylvania:

Vernacular to Spectacular, organized by Donnelly.

On view through May 28, this is the first Heinz Architectural

Center

exhibition to focus exclusively on a single, everyday

type of building.

Donnelly has been hosted by the

Heinz Architectural Center for nearly 10 years while

acting as project

director

for the Buildings of the United States book to be

called Buildings

of Pennsylvania: Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania.

Through her extensive research for the book, Donnelly

discovered

there’s much more to barns than a cursory glance

reveals. In an effort to look beyond the obvious,

for years Donnelly has traversed the 33 counties

comprising western

Pennsylvania. “When you go that far afield,” she

says, “you realize how many fields there are.”

Even

today, this part of the state remains predominately

rural, and, by Donnelly’s count, is still home

to 25,630 farms supporting at least as many barns.

And every

one of them is made to order, built to fit the terrain,

the type of crops grown, and/or the type of animals

raised.

As a result, the region’s barns appear

in varying shapes—ranging from the basic four-walls-and-a-roof

to the truly out-of-the-ordinary octagonal, and an

assortment of sizes from big to just plain huge.

And they are constructed

from a number of different materials, including the

traditional log or timber and the more modern metal

frame. Some are

plain, while others showcase elaborate, sometimes

whimsical barn stars, weathervanes, and lightning

rods. Some

date back to the late 1700s (after all, a well-constructed

barn will stand for centuries), while a few have

enjoyed new

leases on life as offices or homes.

The irony is that

despite their longevity, old wooden barns are often

ill-suited to meet the demands of

modern farming.

Today’s machinery, for example, is too cumbersome

to maneuver in and out of structures built to accommodate

horse-drawn plows.

“

What do you do with these barns?” Donnelly asks. “You

can’t maintain them as museums.” As the exhibition

attests, there’s no single answer to that question.

In many cases, selling the barn’s aged timber

piece by piece is a far more lucrative alternative

to attempting

to maintain the barn itself.

The Laurel Highlands’ Fallingwater has taken

a different tack. It recently renovated and remodeled

a

pair of barns

to create one space for offices and a community center.

The finished product is an environmentally friendly

structure that received the American Institute of

Architects Pittsburgh

Chapter Silver Medal and Green Design Citation in

2005.

Donnelly has also seen her share of barns relegated

to storage facilities and garages. “It’s

a tough and expensive proposition to convert barns

into homes,” she

concedes. Despite that economic fact of life, the

exhibition does highlight one exception to the rule:

a Washington County barn that was dismantled and

then reassembled

as a private residence in Westmoreland County.

In

total, Barns of Western Pennsylvania: Vernacular

to Spectacular features 34 barns dating from 1794

to 2005.

Photographs, farm journals, architectural pattern

books, models detailing the barns’ complex

construction, a full-scale replica of the end wall

of a barn, and

collections of tools and decorative items are used

to tell the story.

It is a story of individual owners

and builders challenging their own creativity and

skills while also finding new ideas and construction techniques

in catalogues and how-to manuals. It is

a story of the agrarian world supporting the region’s

coal, steel, and glass industries by providing the

food supply

for a hungry workforce (particularly before refrigeration

and transportation found a way to combine their efforts).

But the story doesn’t stop there. The Amish

community continues to build timber-framed barns.

And, according

to Donnelly, barns continue to influence a new crop

of architects. “Barns are still a touchstone

for many of us today,” she says.

And then there

are the farmers themselves, whose barns have come

to represent the Vernacular to Spectacular. “The

farmers have been so gracious,” Donnelly says. “I

hope they’ll make the two- to three-hour drive

to see the exhibition. I’ve invited them all.”