Back

Hillman

Hall of Minerals & Gems,

celebrating its 25th anniversary this year, boasts thousands of

nature’s

most dazzling pieces of sculpture—

each with a story to tell.

By M.A. Jackson and Betsy Momich

Should Carnegie Museum of Natural History ever produce a film

about Hillman Hall of Minerals & Gems, the location shoots

would be all over the map, literally. A Carnegie Library

in Montana. A Kaufmann’s window display in downtown

Pittsburgh. A border crossing in Romania. A lead and zinc

mine in Joplin, Missouri.

Scene One: Downtown Pittsburgh,

outside Kaufmann’s department

store. It’s 1969, and Pittsburgh businessman Henry Hillman,

who graduated from Princeton University with a geology degree,

notices the reactions of passersby to one of the store’s

display windows—the one accentuated by a brilliant cluster

of minerals. “People were oohing and aahing more over

the minerals used as display props than the actual merchandise

being sold,” recounts Ron Wertz, president of the Hillman

Foundation.

“

That was one of the factors in our decision to fund the

hall,” Wertz explains. But only

under one condition: that the exhibits in the hall “present

minerals in the manner of sculpture, shown for their beauty

as well as their physical properties and economic uses.”

After

11 years of planning, construction, and more collecting,

Henry Hillman got his wish. For the past 25 years, visitors

have been oohing and aahing over the beauty that resides

in Hillman Hall of Minerals & Gems. The kind of beauty

unmatched by “anything humans can try,” says

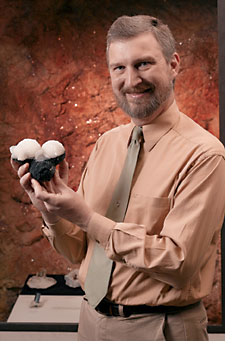

Marc Wilson, collection manager and head of the Section

of Minerals for

the past 13 years, and a walking storybook of the who,

what, when, and where behind every piece in the collection.

Turns out, Hillman Hall of Minerals & Gems isn’t

just a collection of priceless objects. It’s a collection

of stories as varied as the shapes and colors of its stones,

gems, and crystals. Twenty-five years’ worth of stories.

The Quest for Beauty

A professional geologist with a master’s degree in

mineralogy, Wilson has traveled the globe—and, at

times, negotiated it by phone—to strategically build

the Museum of Natural History’s vast collection of

minerals and gems. Unofficially ranked in the top five

in the country for the depth and breadth of its holdings,

Hillman Hall ranks number-one in Wilson’s

eyes for its aesthetic beauty and dynamic display.

He’s

not alone in his thinking. “It’s

one of the most superb displays I’ve ever seen,” says

Donald A. Palmieri, a master gemologist appraiser and a

research associate with the museum’s Section of Minerals

since 1983. “In my opinion, it outshines the [Smithsonian’s]

National Museum of Natural History.”

To hear Wilson

talk about the collection, there’s

no other way to display such beauty than as art. Of the

crystals on display in the hall, he says, “they represent

a microcosm of the order of God’s creation. They

are so perfect, so ordered, so beautiful. And each one

is unique.” Of the process of finding such rare things

of beauty—either by trade, purchase, or an actual

trip into a mine—Wilson describes an amalgam of emotions

often associated with other quests for the beautiful: “lust,

greed, adventure, and vindication.”

No doubt it was

the thrill of adventure—coupled with

the most basic of human instincts, self-preservation—that

Wilson experienced during a trip to the eastern bloc to

secure a batch of minerals the likes of which the world

had never seen.

Covert Operations

Scene Two: The

border crossing of Romania. Marc Wilson is standing before

a group of gun-toting guards as his

latest acquisition—the world’s only known “triple

ball” specimen of calcite with boulangerite (now

displayed among Hillman Hall’s Systematic Collection)—lay

tucked in a camera bag.

In the mid-’90s, Wilson

had realized that Romania’s

most prolific mineral district—one dating back to

Roman times—would probably dry up within the next

six years; and no one in the United States had yet to put

together a comprehensive collection of specimens from the

region.

“

A friend of mine had already successfully entered Romania

and had learned about the ins-and-outs of getting specimens

out of the country,” Wilson recounts. “So he

and I decided to quietly, secretly put together a suite

of the best specimens we could get from the district before

other big museums realized we were doing it.” “

A friend of mine had already successfully entered Romania

and had learned about the ins-and-outs of getting specimens

out of the country,” Wilson recounts. “So he

and I decided to quietly, secretly put together a suite

of the best specimens we could get from the district before

other big museums realized we were doing it.”

Easy

enough. Or not. As Wilson explains, “In any

Third World country, especially one that is still so authoritarian

and so recently communist, you have to know how to

‘

pay your fees.’” In other words, you have to

know who to bribe. “That’s just how it’s

done,” he says, matter-of-factly.

Unfortunately, when

Wilson joined his friend in Romania to bring his newly

acquired Romanian specimens home, he

discovered that all the necessary fees had not been paid

in advance. After lengthy deliberations at the border, his

friend negotiated an opportunity for the specimens

to be removed from the country on another day; and then,

according to Wilson, his friend made a “side negotiation” for

the valuable calcite piece to go home with Wilson that

day. “He then handed it to me in a camera bag as

I stood there in the middle of no-man’s land, somewhere

between Romania and Hungary, and left.”

If it all

sounds a bit like secret-agent work, that’s

because it is. “The acquisition of almost any world-class

piece is a covert operation,” Wilson says. “That’s

why we meet in little rooms in the dark and have discussions

in dingy cafes.”

Behind This Curtain

Wilson’s acquisition of what he considers one of

the best Russian mineral suites went a little smoother.

That is, after the Iron Curtain finally fell.

“

Some of the most significant mineral deposits on Earth

had been sealed behind the Iron Curtain,” Wilson

says. “Collectors risked Siberia, or worse.” But

with the fall of communism, they became free to collect,

buy, sell, and trade, and the rest of the world was more

than ready to oblige. “It was an incredibly exciting

time,” he says.

Wilson contacted a collector he had

heard was obtaining Russian pieces at a good price. The

man sold the best pieces

he could gather to Wilson, and Pittsburgh soon became the

repository of an outstanding suite of 168 minerals from

Russia—some even better than those displayed in Moscow,

Wilson professes.

Like 80 percent of what Hillman Hall has

displayed before and after Marc Wilson’s tenure,

the funding for these rare international purchases came

from the Hillman Foundation.

“

Marc determines what we need and the quality of the item

for sale,” says Wertz, who has become a close collaborator

of Wilson’s. In the case of the 2000 Fluorescence

and Phosphorescence exhibit that demonstrated how minerals

react to ultraviolet light, Wertz fully supported Wilson’s

dream of breaking new ground at the museum.

“

After he completed the exhibit, other museums called to

ask how he did it,” says Collections Assistant Debra

Wilson, Marc’s wife.

“

Marc does everything he can to make the hall shine,” Donald

Palmieri says. “I’m in awe every time I go

in there. Pittsburgh and the museum are very fortunate

to have the Hillman Foundation as a stalwart supporter.”

Nice Surprises

Scene Three: The Carnegie Library in Kalispell, Montana.

It’s the only source of

culture in this northwest-Montana town, and David and Stephanie

Walker frequent it often. During one of their visits, the

Walkers—who have built their own impressive collection

of cut gems—learn about Andrew Carnegie’s museum

of natural history in Pittsburgh and its renowned gem collection.

“

Three years ago, Mrs. Walker called me out of the blue

to tell us she and her husband would like to donate some

of their collection to the museum, starting with $11,000-worth

of cut gemstones,” Wilson says. “I was totally

taken by surprise.” Since then, the couple has donated

two other parcels of their collection valued at $26,000.

And they’re not done.

Personal collectors have been

integral to the museum’s

gem and mineral collection since the 1895 opening of Carnegie

Museums. (See also Acquired Taste.)

The 550-piece personal collection of Gustave Guttenberg,

a curator at

the Academy of Art and Science, was one of the first private

collections purchased by the museum. In 1904, Andrew Carnegie

purchased the 12,000-specimen collection of William W.

Jefferis, a West Chester, Pa., collector, who had amassed

one of the finest private collections in the country. It

put the museum on the map as a mineral repository, and

portions of the Jefferis collection are still displayed

today—including a $15,000 wulfenite and an Arizona

calcite still bearing its 1880s two-dollar price tag.

Still

another private collector, Frederick H. Pough, through

a donation/sale agreement, gave 800 rare and unusual gems

during the planning of Hillman Hall of Minerals & Gems.

And then there was the Oreck family’s $2 million

donation in 2003, which included a 379-carat cut aquamarine and two of the finest specimens of watermelon tourmalines known to exist. “We

were shocked by the magnitude of that donation,” says

Wilson. “The tourmalines put our collection on par

with The Smithsonian.”

Acts of God—and

Man

Scene Four: A

lead and zinc mine in Joplin, Missouri. In this mining

district, corporations and private collectors

had been hitting pay dirt for years (and would continue

to do so through the mid-1900s). On this particularly

productive day in 1895, someone has struck the next best

thing to gold: a yellowish-gold pseudomorph of hemimorphite

after calcite.

Two years later and a few thousand

miles away, Andrew Carnegie became the happy recipient

of that rare and precious piece

of calcite, which was donated to his museum by A.L. Means.

Now encased behind glass in Hillman Hall’s Masterpiece

Gallery, Wilson says “it’s still the signature

specimen of the collection. There are only six in existence.”

While

it was Andrew Carnegie’s international stature

that gave him an edge in attracting and connecting with

some of the world’s great collectors, it’s

Marc Wilson’s never-say-never networking skills that

have managed to do the same for Hillman Hall.

RIght:

This year’s Gem & Mineral

Show celebrates the 25th anniversary of Hillman Hall of Minerals & Gems,

which has a collection that rivals most others in the country. RIght:

This year’s Gem & Mineral

Show celebrates the 25th anniversary of Hillman Hall of Minerals & Gems,

which has a collection that rivals most others in the country.

Wilson calls

finding a cranberry red tourmaline in 2004 “an

act of God,” but it was also a testament to the value

of his extensive network of “friends” and professional

contacts. “I mentioned to a friend how much I’d

love one for the collection and, as luck would have it,

he’d just found one in his collection a few days

earlier and didn’t know why he still had it.” He

sold it at cost to Wilson. In another similar act of God

or man, a Canadian friend of Wilson’s was downsizing

his collection and sold Wilson a much-desired $5,000 quartz

for $750.

The hall’s Quartz exhibit, created in 2002

with support from the Hillman Foundation, is its third

most popular

exhibit, according to Wilson. Exactly how he’s figured

that out is hardly a scientific process. “It’s

the ‘fingerprint index,’” he says, smiling. “We

count the fingerprints left on the display glass at the

end of a busy day to judge an exhibit’s popularity.

The temporary birthstone display wins every time, followed

closely by the gold and quartz exhibits.”

Wilson hopes

to expand the popular birthstone display and make it permanent

someday soon. “And I’d love

to add a piece like the Hope Diamond that’s on display

at The Smithsonian,” he says. “Something else

that would help make Pittsburgh a destination place.”

If

you’re the owner of just such a specimen, Marc

Wilson would love to hear from you.

Back | Top |