Back

Acquired Taste: The

Art of Collecting

By

Leslie Vincen

Do human beings have an instinctual

need to accumulate things? Ask an avid collector,

someone with an almost primal urge to seek out particular

objects of desire and possess them, and the answer

is an emphatic “yes.”

Pittsburgh’s

famous son Andy Warhol was known to be a packrat

who couldn’t part with anything

he found interesting. Whether Warhol collected almost

everything he touched because he thought that someday

it might tell the world something significant about

the past, or just because he grew up poor and was

saving it for later use, we may never know for sure.

But Jessica Gogan, curator of education at The Andy Warhol

Museum, believes

that “whether we know it or not, we all collect

something.”

Compelled To Collect

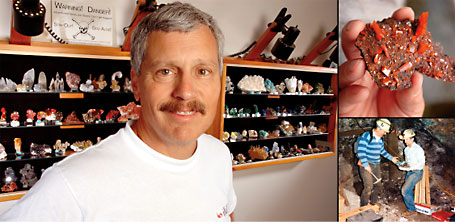

For Bob Kerr, a retired engineer and collector of rare minerals

who volunteers his time periodically to catalogue specimens

for the Section of Minerals at Carnegie Museum of Natural

History, “collecting certainly feels like an instinct.”

Kerr

got his start as a collector in the ’80s when he

moved to Arizona for a job and wondered what he could do during

his time off to combat the intense heat. He decided to go underground.

“

The natural beauty underground was incredible,” he

says. “There

was such a contrast between the desert, with its cactus and

mesquite, and the world below, with all those lustrous, crystalline

forms. It’s amazing what Mother Nature can produce.

I got hooked.”

It’s not easy to go digging for

specimens. It can be dangerous and requires expensive equipment.

Most collectors

find it easier to go to mineral shows and barter for their

next prize. In fact, Kerr builds his collection mostly by

buying, trading, and reselling. He specializes in lead-based

minerals;

a subcategory known for its rich color and luster, like gems.

“

I go to the Tucson Gem and Mineral Society Show every year,” says

Kerr. “It’s a huge show, filled with hundreds

of dealers. Most of the new minerals come in from China,

Russia,

Morocco, and South Africa. It’s fun to wheel and

deal. I haven’t paid a dime for most of my specimens.

Frequently, I’ll buy a box lot with several pieces,

then I’ll

keep the piece I want and sell the rest—hopefully

for what I paid for the whole lot.”

What Kerr loves

most about his collection is the incredible variety of

color that is inherent to lead-based crystals.

He’s

fascinated by the fiery personalities of reds, oranges,

and yellows that are showcased in his home from several

wall-mounted

glass cabinets. One of his signature pieces is a

cerrusite v-twin from Morocco that is one of the largest

single cerrusite crystals ever harvested. Another is a

rare wulfenite

plate, generally considered to be among the best of its

species, which came from the Red Cloud Mine in Arizona.

“

For me, collecting means being able to enjoy the beauty of

your collection as often as you want to…not having to

go somewhere else to see it. My collection is on display for

my own viewing. I don’t consider myself an elite-level

collector,

but I do plan to donate my top pieces to the Museum of

Natural History. Private collections are essential to museums.

Without

private donors, they wouldn’t have much,” he says.

Top RIght: Among Kerr’s favorite

pieces is a wulfenite plate, among the best of its species,

harvested from the Red

Cloud

Mine in Arizona.

BottomRight: Kerr and a friend, John Callahan, who owns the

79 Mine in which the two were working, as they handle a large

aurichcalcite specimen that they unearthed.

PHOTOS: Tom Altany

Private Collections, Public Exhibits

Marc Wilson couldn’t agree more. As collections manager

and head of the Section of Minerals at Carnegie Museum of Natural

History, Wilson is keenly aware of the importance of individual

donors to museum acquisitions.

“

Throughout history, museums would not exist if not for private

collectors,” says Wilson. “During the 1800s and

early 1900s, private collectors actually started museums

by donating their collections. In 1904, Andrew Carnegie purchased

the mineral collection of W. W. Jefferis, which provided

the

core mineral collection of the Museum of Natural History.” (See

also Romancing the Stones)

Not

all donations are exhibit-quality, but many are appropriate

for the reference and research collections of the museum.

“

Exhibit pieces are exquisite, natural works of art,” says

Wilson. “We’re seeking beauty, perfection of crystal

form, freedom from damage, and rarity. An exhibit piece has

a unique brilliance that can’t be duplicated. Ore deposits

around the world are like threatened environments; after a

mine closes, you never see it again. Our job is to salvage

specimens while we can.

“

A collection is like a time capsule—it shows the

personal taste of the collector and what was available

at the time,” Wilson notes. “It builds a picture

of our mineralogical heritage and recognizes the collector

as well as the specimen. We have a pedigree of collections

here.”

Two of the most renowned collectors in the

mineralogical world, Bryan Lees and Bryon Brookmyer, have

each made significant

contributions to Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Recently,

Bruce and David Oreck donated $2 million in cash and specimens

to the museum, including a pair of the world’s finest

specimens of watermelon tourmaline from Bruce’s personal

collection, one of which is known as “City in the

Clouds.” “These

specimens put us on par with the best museums in the world,” says

Wilson. “A signature piece immediately identifies

your museum.

“

Museums owe much to their relationships with private collectors.

We have a network of relationships that covers the globe.

People give to people. That’s why relationships

are so important.”

Richard Armstrong, The Henry

J. Heinz II Director of Carnegie Museum of Art, says

that the same can be said for the world

of art. “We like to have a city of collectors all

interested in the museum. Private collections are an index

of how successful

art museums are in their communities.

“

Easily half of the pieces we have on display are gifts

from private donors. There are always wealthy and generous

people

who have long-standing relationships with museums. For

example, G. David Thompson gave us the DeKooning painting,

Woman VI,

which is one of only six in the world.”

Many collectors

identify themselves by visiting the museum and asking questions

about a particular genre or exhibition.

If they are able to establish a relationship with a museum

professional, it can pave the way for a possible donation

in the future.

“

Occasionally, we know beforehand if someone is planning

to donate art,” says Armstrong. “Sometimes

it’s

a very pleasant surprise, like the table by Japanese artist

George Nakashima. It was a fractional gift —the museum

only had inches—and now we have the entire 12 feet.”

All

donations are significant, even ones the museum might not

keep. Sometimes a piece will be accepted under the

category of property, and then sold to raise cash for an

endowment

fund.

Collecting: A Lifestyle

Herbert and Carol Diamond hadn’t given much thought to

whether or not the art they had purchased might be museum-quality.

That is until their collection of French 19th-century drawings

and bronzes was presented as the exhibition Visions,

Fragments, and Impressions at Carnegie Museum of Art in the fall of 2000.

“

Each piece in our collection is a little jewel,” Carol

Diamond says. Her husband adds, “We buy something

because it appeals to us, and we plan to live with it.”

The

Diamonds started collecting art in 1964, when they purchased

a pair of watercolors by Keiko Minami at an

auction in Brooklyn.“We didn’t really think

of it as collecting, we just enjoyed it,” says Carol

Diamond. “At

the time, we were newly married and didn’t have

much discretionary income. So we decided that rather

than buying

each other birthday or anniversary gifts, we’d

buy art instead.”

After celebrating more than 40

anniversaries, the Diamonds have amassed a celebrated

collection of works on paper,

which includes 19th-century French pieces as well as

an American

collection that combines realist, modernist, and early

abstract art.

“

Collecting has become a lifestyle,” says Herbert Diamond, “and

an intellectual pursuit. When we travel, we go to art museums

to see what’s there and to learn about art. And, of course,

we meet such fascinating people…curators, dealers, other

collectors…and they all share our interest.”

Top Right: One of Herbert Diamond’s favorite pieces;

Man in the City’s Outskirts, by Jean François

Raffaëlli.

Bottom Right: A Pittsburgh scene done by Ernest Fiene, which

served as a study for an oil painting that the artist created

for the 1935 Carnegie International. PHOT OS: Tom Altany

Collections that Teach

The Diamonds prefer works on paper because they’re more

immediate and

represent what the artist was thinking at the time. “A

work on paper was often done as a study for a final work done

in oil,” explains Herbert Diamond. “You can see

the artist working through problems. We have a small pencil

sketch of the Study for the Battle of Poitiers by Eugéne

Delacroix, and you can see that the drawing is not about structure,

but about movement. That was the hallmark of his work—movement

in a static image.”

Most of the Diamonds’ favorite

pieces are examples of social realism that depict “the

way life was.” Carol

Diamond loves the expressive flow of The Seamstresses by

Pierre-Charles Angrand, and her husband appreciates the simple

countenance

of Jean François Raffaëlli’s Man in

the City’s

Outskirts.

Herbert Diamond’s preference for realism

makes reference to his background in medicine. As chairman

of medicine at Western

Pennsylvania Hospital and a practicing rheumatologist, he

often gives talks about art and medicine.

“

One of my mentors in medical school told me that the heart

of medicine is to see things,” he says. “I

showed some of my residents the Portrait of Mademoiselle

Goton by

Octave Tassaert. She’s a middle-aged peasant woman—certainly

not the model of beauty for the human form—and the

sketch reveals her arthritic feet. So I asked them, ‘What

kind of arthritis does she have?’ Nobody had an answer!”

At

times a piece in the Diamonds’ collection will produce

an answer that no one was seeking, purely by chance.

“

Some years ago, I was looking through a journal of clinical

science that’s published by the New York Academy of Medicine,” says

Herbert Diamond. “It’s illustrated with paintings,

and I came upon a Pittsburgh scene that was done by Ernest

Fiene for the 1935 Carnegie International. I recognized it

immediately, because we have the original study. I inquired

about it, and discovered that the painting had been owned originally

by the Kaufmann family.”

“

That’s when we say, ‘Wow, we always liked it,

now we’re really impressed!’” adds

Carol Diamond.

No matter how much time they spend collecting

or how diverse their range of collectibles, most serious

collectors have

one simple characteristic in common—a passion for

collecting. Most buy only what they like and often don’t

consider an object’s investment value.

“

We’ve never sold a piece of art,” says Herbert

Diamond. “But we do seek quality pieces for donation

purposes. We’ve already donated some pieces to Carnegie

Museum of Art, and we anticipate that they’ll end up

with a few more.”

Back | Top |